the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The role of hedgerows in shaping ant (Formicidae) communities in agricultural ecosystems: for a better understanding of agroecosystems functioning, including presumed ecosystem services and disservices

Tom Jamonneau

Gabriel Johnson

Hedgerows are key components in the ecological functionality of mid-western European agricultural landscapes that have seen significant decline in the last 100 years due to intensive agriculture management. These infrastructures promote certain species in and around themselves that contribute to ecosystem services and disservices in farmland that have great socioeconomic fallouts. Few studies have explored how hedgerows shape biological communities and ecosystem (dis)services. Particularly, no study seems to have focused on ants (Formicidae). In the present research work, we explored the effects of both the distance from and management of hedgerows on ant communities. Ants were sampled in Allier, France, using 300 pitfall traps set at five different distances from 20 different hedgerows, categorized as either shrubby or arboreal. To perform taxonomic and functional analysis, we identified ants at the species level and built a functional traits database. We first observed that species richness was higher in arboreal hedgerows compared to shrubby ones. Factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) and redundancy analysis (RDA) also revealed a distance gradient, with greater compositional differences between communities near the hedgerows than those further away. Three functional indices, functional evenness (FEve), functional mean nearest neighbor distance (FNND) and functional dispersion (FDis), were correlated either with the distance gradient or the hedgerow type (arboreal or shrubby). We then identified several functional response traits that drive the functional diversity differences, such as behavioral dominance, worker polymorphism and colony foundation type. Four effect traits we presumed to be ecosystem (dis)services were studied and three of them – soil tilling, insect predation and aphid breeding/nectar thief – were affected in different ways by the distance from and management of hedgerows. This study offers valuable insights into how hedgerows shape agrobiodiversity, generally promoting outcomes beneficial to agriculture. While arboreal hedgerows may support greater ant diversity, shrubby hedgerows appear to provide (dis)services more closely aligned with agroecosystem needs. As a significantly more resilient alternative to intensive agricultural practices, which also threaten biodiversity, we argue that hedgerows will hold a strategic role in the necessary agroecological transition.

- Article

(7164 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(113 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Agricultural land area includes nearly 6 billion ha, representing approximately 40 % of global emerged land surfaces (FAO, 2020). In metropolitan France, it extends across 27 million ha, constituting roughly 50 % of the total surface (French Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty, 2022). This, among other factors, highlights why agriculture is now considered one of the most impactful human activities on biodiversity (e.g., Dudley and Alexander, 2017).

Contemporary French landscapes are the outcome of significant and gradual land-use management since the Middle Ages (Chouquer, 2003; Pognon et al., 1999). From the 11th century onward, there were intensive phases of deforestation aimed at expanding arable surfaces (Aoun, 2010). Subsequently, during the 18th and 19th centuries, land deprivation led to the development of a wooded countryside, now referred to as bocage (Morin et al., 2019). Wooded countryside is usually defined as a landscape consisting of a patchwork of woody vegetal structures (groves, isolated trees, etc.) and a more or less dense hedgerow network (Baudry and Jouin, 2003). Hedgerows being linear vegetal infrastructures composed of bushes, shrubs and sometimes trees that delineate boundaries, and which are maintained by humans (European Commission, 2023; French Biodiversity Agency, 2024). The introduction of a mechanized and industrial agriculture in the early 20th century resulted in significant disturbances to the agricultural landscape, including the re-drawing of parcel boundaries (Pointereau, 2002; Pointereau and Coulon, 2006). Many of the wooded countryside areas were transformed into open fields, eliminating physical field boundaries (Aoun, 2010; Pointereau and Coulon, 2006). As a result, by 2006, France had lost approximately 70 % of the 2 million linear kilometers of hedgerows it had in the early 19th century (Pointereau and Coulon, 2006); and France is still facing a fast decrease in hedgerows according to a more recent survey (Statistics and Foresight Department of the French Ministry of Agriculture, 2014). Ultimately, these profound landscape changes have had a significant impact on biodiversity (Alignier et al., 2020; Burel et al., 1998), including biodiversity beneficial to crops.

Hedgerows induce ecotones as separating distinct ecosystems, each with its own biodiversity (European Commission, 2023; French Biodiversity Agency, 2024). This interface exhibits specific biodiversity, which includes both species specific to the interface itself and some originating from the diversity of the adjacent ecosystems (Garon et al., 2013; Kark, 2013). As a result, the biodiversity associated with hedgerows is often higher than that observed in adjacent more uniform ecosystems (Boutin et al., 2002; Vanneste et al., 2020). For instance, Jahnová et al. (2016) found that hedgerows seem to have more species of ground beetles (Carabidae) than meadows. Moreover, it has been highlighted that the distribution of ant (Formicidae) species abundance can correspond to an “ecotonal effect” (Dauber and Wolters, 2004) and that hedgerows can have a higher functional diversity of ground beetles compared to woodlands and pastures (Gallé et al., 2019).

The biodiversity hosted by hedgerows is implicated in the supplying of ecosystem services and disservices (hereafter (dis)services), several of the first category being particularly beneficial to human, including agriculture (Angel et al., 1992; García de León et al., 2021; Montgomery et al., 2020; Van Vooren et al., 2017). For instance, hedgerows provide provisioning services such as fruit, wood and medicinal plants (Angel et al., 1992). They also offer important indirect services that can influence the abiotic environment on which agricultural systems rely (Angel et al., 1992), along with the storage and maintenance of soil moisture (Hombegowda et al., 2020), mitigation of soil leaching (e.g., Hombegowda et al., 2020), protection of crops from adverse weather conditions (e.g., Viaud et al., 2009), a higher bioavailability of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus (e.g., Van Vooren et al., 2017) and potassium (e.g., Palviainen et al., 2004), etc. Other indirect services could be linked to the biotic environment, such as pest regulation, pollination and organic matter recycling (e.g., Dover, 2019). Those services could particularly enhance the potential of the agroecosystems, increasing yields and making them more resilient (e.g., Montgomery et al., 2020).

How are these services provided, to what extent and with what effectiveness in agricultural fields? Some authors have attempted to address these questions, focusing on different services and taxa. Research on taxa providing pollination and pest control has been more extensive than studies on other services such as seed dispersal and regulation of soil quality (Kratschmer et al., 2024), but overall, the literature remains limited (Holland et al., 2017; Kratschmer et al., 2024). Thus, Albrecht et al. (2020) conducted a review on the effects of flower strips and hedgerows on pollination and pest control services, including studies from Europe, North America and New Zealand. They referenced only 7 out of 35 studies focusing on hedgerows, 6 dealing with pollination and only 1 addressing pest control. Among the 35 studies, few directly addressed insect communities that provide ecosystem services and disservices.

In the present study, we chose to focus on the effects of hedgerow characteristics and of the distance to hedgerows on ant communities. Using ant functional traits, we also discuss the presumed agroecological (dis)services that hedgerows could provide.

Hymenoptera is an insect order that comprises at least 153 000 species, making it one of the most diversified in the animal kingdom (Aberlenc et al., 2021; Aguiar et al., 2013). Within this order, ants (Formicidae) are a globally well-known family, both in terms of taxonomy and ecology (Aberlenc et al., 2021; Ramage and Ravary, 2015). The ubiquitous presence of ants in ecosystems and their numerous biological interactions with the rest of their ecosystems designate them as “keystone” species (e.g., Ramage and Ravary, 2015; Warren and Giladi, 2014). Ants also fulfill the criteria proposed by several authors of bioindicators (Pearson and Cassola, 1992; Rainio and Niemelä, 2003). For example, they play an important role in ground and nutrient cycles and are particularly susceptible to soil disturbances and quality (Lobry de Bruyn, 1999). Numerous agricultural practices such as intensive management, irrigation, drainage, fertilization, mowing or plowing have shown a negative impact on their specific diversity (Folgarait, 1998; García-Navas et al., 2022). Moreover, several studies have demonstrated a correlation between ant species richness and the diversity of various taxonomic groups, such as Collembola (e.g., Majer, 1983), Orthoptera (e.g., Andersen and Majer, 2004), Coleoptera (e.g., Andersen and Majer, 2004; Carvalho et al., 2020) and Termitoidea (e.g., Andersen and Majer, 2004; Majer, 1983), with the biomass of microbes (e.g., Andersen and Majer, 2004) and Embryophyta (e.g., Majer, 1983). To our knowledge, ant communities have rarely been used as bioindicators of ecosystem health in Europe (Duelli and Obrist, 1998; Ramage and Ravary, 2015), while more extensive research has been conducted in tropical ecosystems (Ramage and Ravary, 2015).

In European agricultural landscapes, functional approaches – referring to the characteristics of organisms (e.g., size, diet, color) that determine how they influence and respond to their environments – have been widely applied for several bioindicator groups, such as birds (e.g., Oksuz and Correia, 2023), wild plants (e.g., Carmona et al., 2020), spiders and ground beetles (e.g., Gallé et al., 2019; Kubiak et al., 2022). For three decades, the functional diversity of ants has also been primarily examined in Australia (e.g., Andersen, 1995), the USA (e.g., Andersen, 1997) and New Caledonia (Ramage and Ravary, 2015). The approach was mainly focused on functional species groups (Ramage and Ravary, 2015), but recently, ant functional trait analyses have begun to be used in Europe (Arnan et al., 2014, 2017; Scharnhorst et al., 2021). Interestingly, Scharnhorst et al. (2021) showed that old established grasslands can increase ant species richness and abundance and provide a consistent and resilient amount of biocontrol services in agroecosystems; they also showed that a certain time is needed to reach a functionally rich ant community including specialist species. Eventually, while some rare studies have considered the effects of hedgerows on ants (Dauber and Wolters, 2004; Zina et al., 2022), none seemed to have explored functional diversity in this context.

Given that hedgerows are key ecotonal structures in agroecological systems whose diversity depends on human management, we investigated the taxonomic and functional components of ant biodiversity along a distance gradient near 20 hedgerows, considering their characteristics and using pitfall traps. We first hypothesized that ant species richness will decrease while moving away from hedgerows. If so, we expected that several ant functions, such as insect predation, will decrease or even disappear along this distance gradient, leading to a loss of functional performance, the latter being perhaps a consequence of lower functional redundancy and diversity. However, we anticipated that all functions could also be preserved across the gradient, with species being replaced by others with similar functions. Implications of hedgerows and their characteristics on agrobiodiversity and ants presumed ecosystem (dis)services were ultimately discussed.

2.1 Sampling of ants

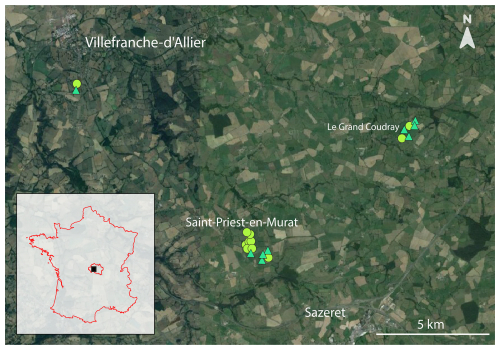

Field sampling was carried out in the department of Allier in central France between 13 and 20 August 2020 (Fig. 1). This choice was made since, compared to other non-social arthropods, seasonality has less impact on ant occurrence because they are colonial organisms, with colonies remaining more or less active throughout the year (Parr and Bishop, 2022). The studied area was an agricultural bocage with cultivated plots (with rye grass, clover, oats and maize) and grazed ones (by cows and sheep). Several agricultural plots and the surrounding hedgerows were studied with the permission of their owner.

Figure 1Geographic localization of studied hedgerows in the Allier department, France. The circular points represent arboreal hedgerows (n = 11) and the triangular points represent shrubby hedgerows (n = 9) (see Sect. 2.2 Hedgerow characteristics for further details). Each white locality name has a font size corresponding to its population size. © background: Google Earth Pro.

Ants were collected using Barber traps, commonly known as pitfall traps, which remain widely employed for studying ground-dwelling arthropods like ants, due to their ease of use, efficiency (notably for temperate open lands), adaptability, standardness and cost-effectiveness (Brown and Matthews, 2016; McCravy, 2018). White plastic circular cups measuring 15 cm in height and 8 cm in opening width were chosen and filled with a mixture of water, soap and salt to sink and preserve arthropods, following recommended practices (e.g., Brown and Matthews, 2016).

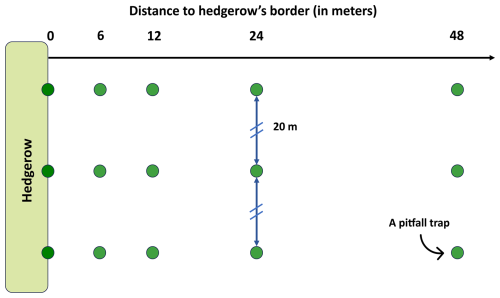

Pitfall traps were positioned in three distinct agricultural areas, covering a total of 20 agricultural hedgerows (Fig. 1). All adjacent agricultural plots were rather individually homogenous, which is representative of the studied landscape. Traps were placed at five distinct distances on a transect from the hedgerow border to the center of the agricultural plot, following a gradient of 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 m. This incremental spacing was chosen to maximize the sampled plot's area without increasing sampling effort. Additionally, the 48 m value approximately corresponds to a proposed distance threshold of the impact of the hedgerow on the yield of adjacent crops (Van Vooren et al., 2017, 2018). Each hedgerow was studied using three repeated transects considered pseudo-replicates, resulting in a total of 20 × 5 × 3 = 300 traps. Transects were positioned 20 m apart from each other (Fig. 2), considering the generally estimated foraging or dispersal distance of European ant workers to be under a distance of 10 m around the nest (e.g., Gordon, 1995; Traniello, 1989). To ensure a uniform sampling duration of 7 d, traps were set and collected in the same order. Individuals were preserved in 80 % ethanol solution when collected.

Figure 2Sampling scheme for a hedgerow. Each green point represents a pitfall trap (i.e., a Barber trap). These traps were placed at five distances from the hedgerow border to the center of the agricultural plot, following a gradient of 0, 6, 12, 24 and 48 m. Three pitfall traps were placed at each distance, forming three transects separated by a distance of 20 m.

2.2 Hedgerow characteristics

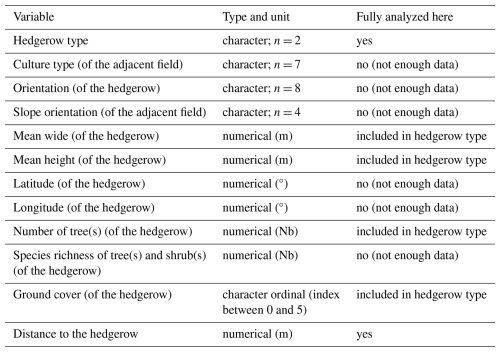

Hedgerows and adjacent land characteristics can impact the biodiversity of macro-invertebrates within and around them (Barr et al., 2005). In this study, we defined two types of hedgerows: arboreal and shrubby. To achieve this categorization, we assessed for each hedgerow its height, width, geographic position and orientation, ground cover, tree species count and richness, vegetation community and adjacent agricultural use (including plant and cattle cultures) and slope direction from the hedgerow (see Table A1).

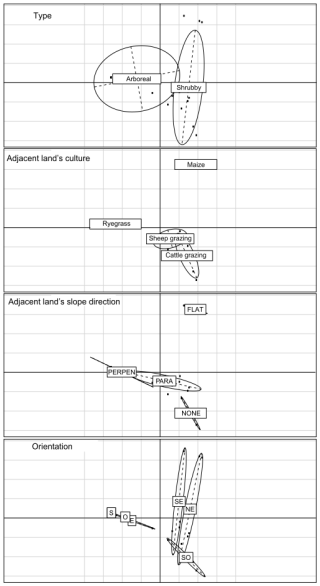

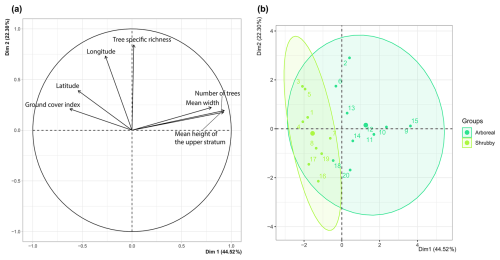

The impact of hedgerow geographical position (latitude and longitude), orientation, tree species richness, vegetation community, and the adjacent land culture and slope direction could not be further examined due to a lack of statistical power. However, preliminary multidimensional analyses (principal component analysis (PCA) and multiple correspondence analysis (MCA); FactoMineR (Kassambara and Mundt, 2020) and FactoExtra (Lê et al., 2008)) revealed no apparent correlation between these characteristics and hedgerow type (Fig. A1). Therefore, these variables are not a priori involved in our hedgerow types.

During fieldwork, two distinct types of hedgerows were observed: arboreal and shrubby, which were later differentiated based on vegetative structure. Specifically, arboreal hedgerows were defined as those exceeding 5 m in height along at least 75 % of their length (n = 11) and with at least five trees (i.e., base diameter ≥ 20 cm). The remaining hedges (n = 9) were categorized as shrubby. Hedgerow type allowed us to synthesize four hedgerow-related variables – height, width, ground cover and tree count – as confirmed by the PCA preliminary analysis (FactoMineR and FactoExtra; Fig. A2a, b). For the remainder of the study, we primarily used these two hedgerow types to assess the impact of hedgerow characteristics and management on agricultural ant communities.

2.3 Ant identification

Ant identification was carried out at the species level, in 2021 and 2022, using recent taxonomic studies and keys specific to the Western Palearctic region (Lebas et al., 2016; Radchenko and Elmes, 2010; Rigato, 2011; Schlick-Steiner et al., 2006; Seifert, 1988, 1992, 2007, 2012; Seifert and Schultz, 2009; Steiner et al., 2010) and a Leica MZ4 stereomicroscope. Only worker ants were identified, as sexual individuals do not indicate the establishment of a species in a given area (Table S1 in the Supplement).

2.4 Ant functional traits

For each ant species, 18 functional traits were retrieved from the literature (Table S2). Fourteen of them are response traits frequently used for their representativity of ant global functionality and were based on the work of Arnan et al. (2017). The last four were effect traits, chosen for their presumed implication on the agricultural yields and management. The following 14 response traits were selected: worker size, worker polymorphism, diurnality, behavioral dominance, diet (seed eating, insect eating and liquid-food eating), foraging strategy (individual, group and collective), colony size, number of queens, number of queens, nests and colony foundation type. Species reference values were retrieved from Arnan et al. (2014, 2017) and Scharnhorst et al. (2021). The four effect traits can be assimilated to the following presumed ecosystem (dis)services: seed dispersion, insect predation, aphid (Aphidoidea) breeding/nectar thief and soil tilling. For each of these four effect traits, an index was newly built for this study to estimate the associated presumed ecosystem (dis)services. The seed dispersion index was created based on data regarding seed displacement distances by ants, with four categories: 0, 0–0.3, 0.3–2 and > 2 m, using the following resources to determine species displacement distances (Gómez et al., 2005; Gómez and Espadaler, 2013; Gorb and Gorb, 1999; Handel and Beattie, 1990; Prokop et al., 2022; Servigne, 2008). We defined, based on the literature, the location of ant species nests using a binary system: species that predominantly locate their nests in an uncovered soil and those that do not (under rocks, dead trunks, etc.) (Lebas et al., 2016; Seifert, 2018). This binary variable was interpreted as a soil tilling index adapted to agricultural fields. For insect predation and aphid breeding/nectar thief, we used the insect eating and liquid-food eating indices developed by Arnan et al. (2017). As the magnitude of the effect of these traits on the ecosystem depends on the biomass of the considered ants, and as we wanted to quantify this effect, we multiplied these four indices by the worker and colony mean sizes of each respective species.

2.5 Statistical analysis

A substantial number of traps (n = 63) were not used for further analyses because they were either damaged by cattle or wild animals or they accidentally caught vertebrates (five lizards (Podarcis sp.) and three green frogs (Pelophylax sp.)), the latter potentially skewing the attractivity of our traps. Nevertheless, a Pearson's χ2 test showed that unused traps were not more prevalent at one distance of hedgerows compared to another (pvalue = 0.188), nor for one of the defined two hedgerow types (pvalue = 0.966); allowing further comparisons between these data classes.

Since we performed three transects for each hedgerow, we computed the sum of the incidence frequencies over the three pseudo-replicates of each distance. Thus, the community matrix was built with sum of incidences ranging from 0 to 3. In the subsequent analyses including those on species richness, this approach accounted for the non-independence of pseudo-replicates.

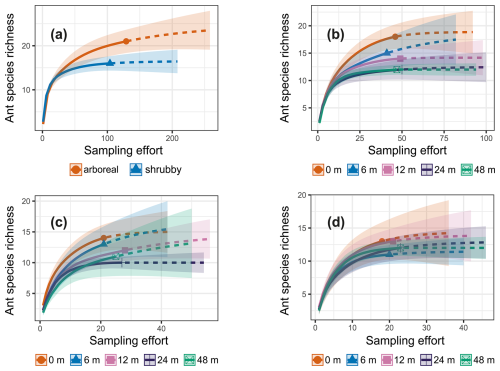

Sampling completeness was tested for each hedgerow distance and for the two hedgerow types: arboreal and shrubby, using accumulation curves (Hsieh and Chao, 2022). These are designed to determine whether ant communities have been sufficiently sampled for each data category, ensuring their comparability, and to provide an estimate of the expected number of species in a given community (Colwell et al., 2012). Given that ants are social insects, usually forming populous colonies, the measured abundance of a species is largely dependent on proximity to ant nests rather than the density of ant nests (Gotelli et al., 2011; Ramage and Ravary, 2015). For that reason, our sampling curves were done working with sampling-unit-based incidence frequency data (data type = “incidence_freq”, iNext R package; Hsieh and Chao, 2022), as recommended by Gotelli et al. (2011). To say it in other words, we only used the identity of the species present in each trap.

The impact of hedgerow distance and type on ant beta diversity was tested using Mantel matrix permutation tests (vegan R package; Oksanen et al., 2024). To do so, Jaccard beta diversity and two of its components (richness and turnover) were first computed using hedgerow × distance ant communities (adiv R package; Pavoine, 2022). Mantel tests compared beta diversity matrices to a distance matrix between each trap × hedgerow distance. To compute this last matrix, the dist function and the Euclidean method were used (stats R package; R Core Team, 2024). Mantel tests were performed with 9999 permutations and both with Pearson and Spearman distances to account for potential non-linear correlations.

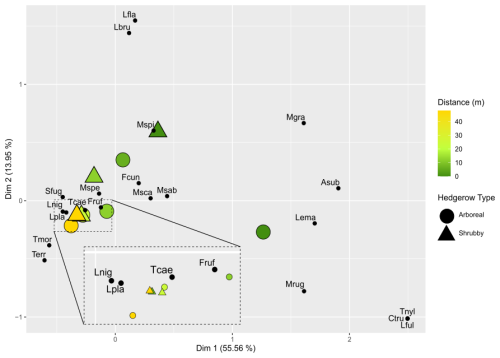

To complete the information given by the above indices, a factorial correspondence analysis (FCA) and a redundancy analysis (RDA) (vegan R package; Oksanen et al., 2024) allowed, respectively, to spatially visualize and statistically test the species–structure differences between ant communities. For visibility purposes, the FCA was computed for each distance grouping hedgerows following their type.

Eight functional indices (i.e., functional dispersion (FDis), functional richness (FRic), functional divergence (FDiv), functional evenness (FEve), functional specialization (FSpe), functional mean pairwise distance (FMPD), functional mean nearest neighbor distance (FNND) and functional originality (FOri)) were computed for each hedgerow × distance combination based on the functional response traits (mFD R package; Magneville et al., 2022).

Figure 3iNext accumulation curves generated using sampling-unit-based (pitfall traps) incidence frequency data. The solid lines represent the observed species richness, while the dashed lines show the expected species richness if sampling efforts were doubled. The colored bands indicate standard errors. The data are presented as follows: (a) comparison between arboreal and shrubby hedgerows, (b) species richness across the five sampling distances, (c) for arboreal hedgerows the species richness at the five sampling distances and (d) for shrubby hedgerows the species richness at the five sampling distances.

Community-weighted means (CWMs) and community-weighted variances (CWVs) of the effect and response traits were measured for each hedgerow × distance community k following Eqs. (1) and (2):

where aik is the relative abundance of species i in community k and tik is the trait mean of species i in community k.

To test for a significant effect of hedgerow distance and type, we used both general linear models (GLMs; stats R package; R Core Team, 2024) and Kruskal–Wallis (KW) non-parametric and Dunn post hoc tests (FSA R package; Ogle et al., 2025). Effectively, GLM, as our default option, was sometimes not usable because of heteroscedasticity (Durbin–Watson test; lmtest R package; Hothorn et al., 2022) leading us to implement KW as an alternative and Dunn to highlight the pairs of conditions significantly different one from the other. Thus, the distance parameter was either continuous in GLM or categorical in KW and Dunn tests. For GLMs, we used a quasi-Poisson family for the species richness that is quantitative discrete and according to the high data variability and a Gaussian family for all other quantitative continuous variables. Concretely, we computed one of the two methods for ant species richness, each functional indices, CWMs and CWVs (vegan R package; Oksanen et al., 2024). Model specification was as follows:

as pre-analyses including the interaction factor for the two explanatory variables using GLMs or, when needed, a non-parametric alternative (Scheirer–Ray–Hare test; rcompanion R package; Mangiafico, 2025) had shown no significant interaction (results not illustrated).

Figure 4Factorial correspondence analysis (FCA): multidimensional representation of ant community plots based on hedgerow distance and type. For visibility purposes, the FCA was computed for each distance grouping of hedgerows following their type. The first two dimensions are shown along with their associated percentage of explained variance. The distance from the hedgerow is represented by a color gradient (dark green and orange for short and long distances, respectively), while hedgerow type is indicated by shapes: round for arboreal hedgerows and triangular for shrubby ones. Species in these communities are represented and abbreviated using the first letter of the genus name, followed by the first three letters of the species name.

3.1 Taxonomical analysis of ant communities

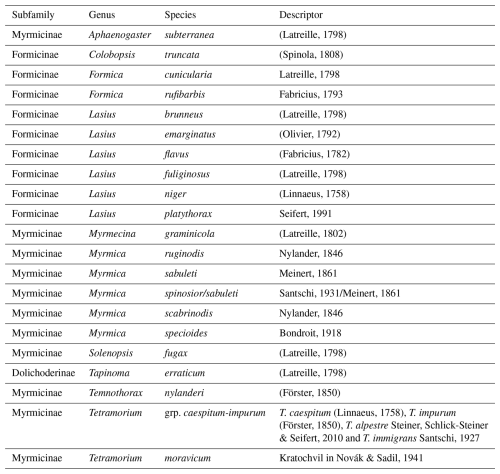

A total of 2556 ants were collected using pitfall traps and identified at the species level (Table S1). Due to the known presence of Myrmica spinosior Santschi, 1931 and M. sabuleti Meinert, 1861 in Allier, and the difficulty in distinguishing these two sister species (both morphologically and ecologically speaking) even with morphological ratios (e.g., Radchenko and Elmes, 2010), we opted to group them as a single species. In total, 21 species from 10 genera and 3 subfamilies of Formicidae were recorded (Table A2). The most abundant species was Tetramorium grp. caespitum-impurum (n = 969), while Lasius brunneus (Latreille, 1798) and Colobopsis truncata (Spinola, 1808) were represented by a single individual.

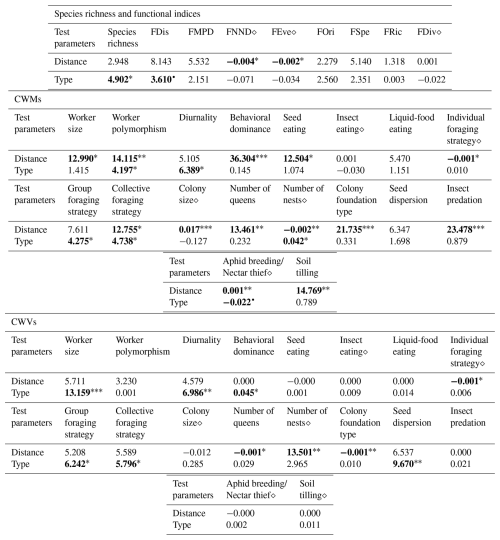

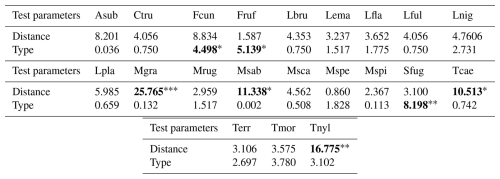

Table 1Results of the general linear model (GLM) and Kruskal–Wallis analyses conducted for the species richness, functional indices, CWMs and CWVs of functional traits and presumed ecosystem (dis)services. GLM outputs are indicated with the symbol “⋄” and all other outputs belong to Kruskal–Wallis analyses. We present the Kruskal–Wallis χ2 statistics and GLM coefficient estimates along with the significance levels of the pvalues, indicated as follows: • < 0.06, ∗ < 0.05, < 0.01, < 0.001. Values are rounded to three decimal places (0.001) and set in bold when statistically significant. For “Type”, in the case of GLM, the intercept corresponds to the arboreal category.

The iNext accumulation curves indicated that species richness in both arboreal and shrubby hedgerows, as well as across the five sampling distances (both combined and for each hedgerow type), approaches a plateau with our sampling effort, as supported by the mathematically extrapolated richness (Fig. 3). However, species richness may be slightly underestimated, notably in arboreal hedgerows (Fig. 3a). The accumulation curves revealed two trends: species richness increases with proximity to hedgerows and is higher in arboreal hedgerows compared to shrubby ones (Fig. 3). The associated KW test and a graphical examination only confirmed that ant species richness is significantly greater in arboreal hedgerows compared to shrubby ones (Table 1 and Fig. A3a).

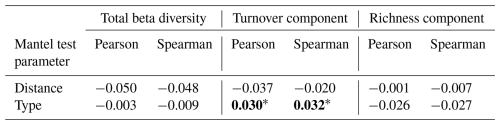

Table 2Results of Mantel matrix permutation tests with Pearson and Spearman correlations between the hedgerow distance and type matrix, and the Jaccard beta diversity matrix with two of its components (richness and turnover). The Mantel statistic is provided and the significance of the pvalue is indicated as follows: ∗ < 0.05, < 0.01, < 0.001. Values have been rounded to three decimal places (0.001) and set in bold when statistically significant.

Mantel tests indicated that distance has no significant effect on beta diversity nor its two studied components: turnover and richness (Table 2). No effect was further found between 0 and 48 m, when only comparing these two distances (results not illustrated). Regarding the type of hedgerow, while beta diversity and its richness component showed no significant effects, the turnover component displayed a correlation with both Pearson and Spearman methods (Table 2).

The RDA permutation analysis indicated a significant effect of hedgerow distance on ant communities (explained variance = 27.85, F statistic = 3.179, df = 1, pvalue = 0.037), while the type of hedgerow showed a non-significant tendency in influencing ant communities (explained variance = 16.44, F statistic = 1.876, df = 1, pvalue = 0.125). The FCA first axis, describing 55.56 % of the variance, particularly differentiated ant communities based on their distance from hedgerows, following a clear gradient (Fig. 4). However, this gradient was not consistent at 6 m for shrubby hedgerows. Ant communities at 0 m were particularly characterized by C. truncata and Myrmecina graminicola (Latreille, 1802), and those at 48 m by Tetramorium moravicum Kratochvil in Novák & Sadil, 1941 and Tapinoma erraticum (Latreille, 1798). Moreover, the difference in ant communities between hedgerow types was more pronounced at shorter than at greater distances from hedgerows. When focusing on the seven species occurring only at 0 m (n = 4) and/or 6 m from hedgerows, M. graminicola and Temnothorax nylanderi (Förster, 1850) showed significant differences in incidence when comparing these hedgerow distances (KW analyses, Fig. A4c, g, Table A3). The occurrences of some species had a trend to increase/decrease with distance gradient, this being significant for T. grp. caespitum-impurum which more frequently occurred at a greater distance to hedgerows (Fig. A4f, Table A3).

3.2 Functional analysis of ant communities, including presumed ecosystem (dis)services

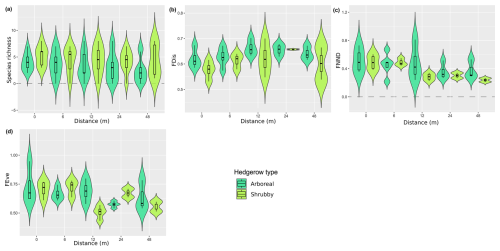

Regarding the functional diversity of ant communities, two functional indices exhibited significant correlations with hedgerow-related factors, while another one showed a marginally significant correlation (Table 1 and Fig. A3c, d). According to GLMs, FNND and FEve were negatively correlated with hedgerow distance, while FDis (KW test, χ2 = 3.610, pvalue = 0.057; graphical examine) was higher in arboreal hedgerows than shrubby ones.

Furthermore, 10 of the 14 functional response traits were significantly correlated with hedgerow distance (Table 2 and Fig. A5a, b, d–f, h, i–l, including Dunn tests). For instance, traits such as individual foraging strategy, number of queens, worker size and number of nests decreased with distance from hedgerows. Conversely, worker polymorphism, behavioral dominance, seed eating, collective foraging strategy, colony size and colony foundation type increased with distance from hedgerows.

The community-weighted variance (CWV) of foraging strategies (individual, group and collective), number of nests and colony foundation type were significantly correlated with hedgerow distance, with greater variance observed at shorter distances from hedgerows (Table 2 and Fig. A6d, g–i, including Dunn tests).

Additionally, five functional response traits were significantly correlated with hedgerow type (Table 2 Fig. A5b, c, g, h, k, including Dunn tests). Worker polymorphism, diurnality, number of nests and group foraging strategy had higher values in association with shrubby hedgerows, while collective foraging strategy showed higher values with arboreal ones. The CWV of worker size, diurnality, behavioral dominance, group foraging strategy, collective foraging strategy and number of nests were significantly correlated with hedgerow type; with shrubby ones showing higher variance than their arboreal counterparts (Table 2 and Fig. A6a–c, e, f, including Dunn tests).

Among functional effect traits, insect predation, soil tilling and aphid breeding/nectar thief were correlated with hedgerow distance, with higher values at shorter distances from hedgerows for insect predation and soil tilling, and lower values at shorter distances from hedgerows for aphid breeding/nectar thief (Table 2 and Fig. A5n–p, including Dunn tests). Aphid breeding/nectar thief was also correlated with hedgerow type, showing higher values in arboreal ones. For seed dispersal, we only observed a decreasing trend with distance in the case of arboreal hedgerows (Fig. A5m).

In metropolitan France, there has been a significant loss of wooded countryside, including their main components, hedgerows, in favor of more open fields. These landscape changes affect biodiversity at different scales, impacting the functionality of the considered ecosystems. While the structure of agricultural landscapes has been relatively well studied for several groups or organisms, such as birds or ground beetles, for which the associated ecological functions have been recently highlighted, knowledge about ants remains limited. Moreover, even for the more documented groups mentioned above, agro-ecological (dis)services have rarely been the primary focus of existing studies.

Here, we explored the effects of the distance from and two types of hedgerows (i.e., arboreal and shrubby) on ant communities in the French agroecological landscapes of Allier. Overall, we found that both factors influenced ant species richness, several functional diversity indices, and multiple functional response and effect traits.

4.1 Taxonomic analysis of ant communities

Ant species richness was higher in arboreal hedgerows than in shrubby ones. Conversely, Zina et al. (2022), who used pitfall traps in a Portuguese alluvial plain, did not find any difference in species richness between two more general categories of ecological infrastructures: woody and herbaceous. By grouping shrubby and arboreal hedgerows within their “woody” ecological infrastructures, Zina et al. (2022) might have lacked precision or combined highly variable structures, preventing them from detecting a difference. Shrubby hedgerows could therefore be structurally closer to herbaceous infrastructures in terms of ecological niches, and indeed in terms of ant taxonomic communities, than arboreal hedgerows. Additionally, we were unable to find any study seems that compared different types of hedgerows in terms of insect richness. However, as highlighted here, hedgerow structure likely influences species richness.

On the other hand, ant species richness showed an increasing trend with proximity to hedgerows. Zina et al. (2022) further found a significant increase in ant species richness with the proximity to ecological infrastructures. We argue that the greater distance range they studied (0 to 600 m) allowed them to detect a clearer difference between ant community distances. Notably, their species richness at 0 and 50 m was not visually different (see Fig. 5 of their article). This aligns with our first hypothesis that species richness would decrease as distance from the hedgerow increases.

To further explore these differences in species composition and to investigate other aspects of ant communities, we then focused on beta diversity.

Few significant differences in beta diversity (or its components) were found: only turnover was significantly different from 0 (null hypothesis) when comparing arboreal and shrubby hedgerows. This indicates a substantial species replacement between our two hedgerow types. Conversely, KW tests found a significant difference in species richness between hedgerow types. This difference could be attributed to methodological differences, specifically the richness component of the Jaccard beta diversity (Mantel test) accounting for species identity. As a result, part of the variation in richness detected by KW tests may actually be captured by the turnover component of Jaccard beta diversity, rather than by the richness component itself.

Interestingly, in his review of ant community differences in fragmented landscapes, Crist (2009) found a significant turnover between habitat fragments, particularly at a small scale (e.g., the agricultural plot). Additionally, he noted that substantial changes in species richness between ant communities occur primarily at the landscape scale. Our study, focusing on a local scale, aligns with these findings, as turnover was the major difference between hedgerow types, with species richness being secondary.

To further explore these composition differences, we conducted FCA and RDA analyses, notably to examine the species associated with these variations.

These analyses revealed a distance gradient, with more important composition differences between communities near hedgerows than those far from them. We argue that agricultural disturbing practices act as environmental filters, selecting ant species and shaping ant community composition. Also, the presence of hedgerows seems to moderately influence ant agricultural communities, at short distances from them. For instance, M. graminicola and T. nylanderi seemed to be ecologically restricted before the threshold of 6 m from hedgerows.

We also noticed that the distance gradient was not evident for 6 m ant communities. Although preliminary analyses did not reveal any correlation between the number of unusable pitfall traps and hedgerow type, distance, or their interaction, approximately 15 % fewer traps were usable near shrubby hedgerows at 6 m. This may explain the observed result.

Furthermore, it seems that the differences in composition highlighted by the species turnover between shrubby and arboreal hedgerows occurred mainly for communities at 0 m. At this distance, one species tended to be more present in arboreal hedgerows (T. nylanderi), and four species were more associated with shrubby hedgerows, among which three were significantly more abundant: Formica cunicularia Latreille, 1798, F. rufibarbis Fabricius, 1793 and Solenopsis fugax (Latreille, 1798); T. moravicum showed a similar, though non-significant, trend (Fig. A1, Table A3). What is more, infrequent species in our study (< 5 occurrences) tended to be more present at 0 m, especially in arboreal hedgerows. For instance, C. truncata and Lasius fuliginosus (Latreille, 1798) were found only once at 0 m in an arboreal hedgerow. These rare species present mainly in one hedgerow type are the principal explanation for the turnover presented above. On the other hand, these species, notably C. truncata and L. fuliginosus, are known to nest in old tree roots or trunk holes (Markó et al., 2009; Radchenko, 1997; Ślipiński et al., 2014). The presence of such species near arboreal hedgerows could be linked to the vegetation layers that these hedgerows include compared to the fields and, to a lesser extent, to shrubby ones. Subsequently, this would offer more ecological niches, including nesting and feeding resources, as stated by the “habitat heterogeneity hypothesis” (MacArthur and MacArthur, 1961; MacArthur and Wilson, 2001).

Do these specific composition differences affect the functionality of these ecosystems? To explore this question, we investigated the ecosystem functionality of ant communities.

4.2 Functional analysis of ant communities

Functional evenness and functional mean nearest neighbor distance had higher values at short distances from hedgerows, with a step between 6 and 12 m, more pronounced for the latter index in arboreal hedgerows. This implies that there are greater minimal functional differences between species and that functions are more evenly distributed near hedgerows. Additionally, the low values observed for the FNND low values involved a higher functional redundancy at great distances from hedgerows. Moreover, functional diversity indices such as functional richness or functional diversity were not correlated with the distance gradient from hedgerows. This contrasts with our hypothesis that increasing distance to hedgerows would lead to a loss of functional performance, reflected in lower values of functional redundancy and diversity.

Agricultural fields are ecosystems subject to regular disturbances that exert selective pressures on various arthropod groups, such as ground beetles (Carabidae) (Burel et al., 2004) and bumblebees (Apidae) (Westphal et al., 2003). In such ecosystems, the lower complexity (e.g., of the vegetation) and those disturbances may lead to lower functional diversity and higher redundancy, respectively. Ultimately facilitating the presence and abundance of (more) generalist species (e.g., Westphal et al., 2003). Our results appear to validate this, as ant species at great distances to hedgerows were functionally redundant and supposedly ecologically generalist. For instance, four species (F. rufibarbis, F. cunicularia, Lasius niger (Linnaeus, 1758) and T. grp. caespitum-impurum), mainly found at 24 and 48 m from hedgerows, are found in highly anthropic areas, such as gardens and agricultural fields (Lebas et al., 2016).

Continuing onward, functional dispersion was higher in arboreal hedgerows than in shrubby ones, implying that arboreal hedgerows have species performing more distinct functional roles. Thus, the more habitat-complexified and less-often-perturbed arboreal hedgerows were found to be functionally more dispersed and less redundant compared to shrubby ones, hosting for instance C. truncata, which can be considered a specialist species, notably for its arboreal-nesting specificity (Markó et al., 2009).

These more distinct functions in arboreal hedgerows may suggest better functional performance from an agricultural perspective. Since functional richness was not correlated with hedgerow type – both types having a similar functional volume – the additional functions associated with greater functional dispersion in arboreal hedgerows are thought to be more closely related to, and indeed more complementary to, the other functions. Ultimately, they may also be more compatible with agricultural practices (but see discussions below).

García-Navas et al. (2022) found differences in ant communities for two functional indices: functional richness and functional originality, when comparing landscape structures. It is possible that these two indices, which were not significant in our study, are more suited to a larger study scale (as in García-Navas et al., 2022). However, other indices used in this study, which highlighted differences, could be more appropriate for the agricultural plot scale. Yet, as far as we know, no study at the landscape scale has tested these indices (e.g., FNND or FDis) for arthropods in an agricultural context.

We then seek to identify which functional traits could influence the previous functional diversity differences.

Here, ant communities in shrubby hedgerows were more polymorphic, diurnal group foragers, frequently associated with high numbers of nests, and fewer collective foragers compared to those in arboreal hedgerows. Within the literature, this comparison of structural hedgerow categories seems to have been restricted to other groups of arthropods, with (e.g., for ground beetles; Theves and Zebitz, 2012) or without a functional focus (e.g., for saproxylic beetles; David and Keith, 2009). Interestingly, Theves and Zebitz (2012) suggested that old hedgerows tend to host more specialized ground beetles species. Similarly, in our study, ant species were less polymorphic (and possibly more specialized) in the presumably older arboreal hedgerows.

For the distance gradient from hedgerows, as we moved further away from them, species became smaller, more polymorphic, dominant and granivorous. Among the three foraging strategies, species near hedgerows rather displayed an individual strategy, while the collective foraging ones became more prevalent as we moved farther away. Still, only two species (C. truncata and M. graminicola) exhibited an individual foraging behavior and these were infrequent and observed exclusively near the hedgerow. On the other hand, our study underlines that, going further from hedgerows favors granivorous species. We argue that Tetramorium spp. and more generally granivorous ant species are characteristic of opened habitats, such as the agricultural fields studied here. However, our findings differ from results reported in agricultural Mediterranean areas, where proximity to hedgerows favored granivorous traits, likely linked to the influence of dominant granivorous species such as those of the Messor genus (Zumeaga et al., 2021). Boinot et al. (2024) also pointed out that granivorous ground beetle species were more abundant in landscapes with the greater length of hedgerows. Following that, hedgerows may locally enhance weed control by favoring granivorous taxa (Baraibar et al., 2009; Westerman et al., 2012), potentially offsetting nutrient loss and helping maintain yields (Baraibar et al., 2011). What is more, colony size increased at greater distances from hedgerows; however, at these distances, the number of queens and nests within colonies reduced. Additionally, colony foundation became more independent at greater distances from hedgerows. Kreider et al. (2021) observed similar shifts in canopy ant functional traits (e.g., colony size and diet) along a land-use gradient from forest to more intensively managed agricultural fields in the tropical region of Sumatra. Ultimately, Scharnhorst et al. (2021) found that younger environments tended to support larger ant colonies, and we suggest that the agricultural field, with its frequent and significant disturbances, could be considered a “younger” environment compared to the less often perturbed hedgerow ones.

All these functional traits, which are prevalent at greater distances from hedgerows, support the previously mentioned generalist/pioneer species hypothesis. For example, smaller species, omnivorous, with larger colony size (Scharnhorst et al., 2021) and independent colony foundation type, may facilitate the colonization of remote/perturbed environments.

The variance of all (individual, group and collective) foraging strategies, number of queens, number of nests and colony foundation type were significantly correlated with hedgerow distance, with greater variance observed at shorter distances from hedgerows.

On the other hand, traits that exhibited significant differences between hedgerow distances in community-weighted variances generally showed greater variability near hedgerows, such as colony foundation type, number of nests and queens and foraging strategy. The decrease in functional variability with the distance from hedgerows aligns with our observations on functional diversity indices and vegetal layers number and gives precisions on the involved response traits.

We then examined the presumed impacts of these functional differences among ant communities on presumed ecosystem (dis)services by analyzing functional effect traits.

4.3 Presumed (dis)services analysis provided by ant communities

We observed a reduction in the soil tilling (dis)service, which corresponds to soil bioturbation, as the distance from hedgerows increased. Among the few studies in Europe that have focused on ant-driven soil bioturbation, a trend has emerged showing that this (dis)service tends to be higher in open habitats (e.g., grassland) than in closed ones (e.g., broad leaf forest) (Taylor et al., 2019; Viles et al., 2021). Notably, three ant genera – Formica, Myrmica and Lasius – which were also recorded in our study, seem to play a major role in soil bioturbation in European open habitats (Taylor et al., 2019; Viles et al., 2021). Our study complements this trend by suggesting that, at local scale, the presence of arboreal structures within open habitats may promote this (dis)service.

Generally, ant-driven soil bioturbation has been documented to enhance infiltration rates, increase nutrient contents such as nitrogen and phosphorus, neutralize soil pH, accelerate decomposition and modify microbial activity (Frouz and Jílková, 2008). Thus, from an agricultural perspective, it can therefore be considered an agroecological service. However, in certain cases, these modifications might be disadvantageous, particularly regarding microbial activity and pH compatibility with some cultivated species.

Insect predation, in the same way, decreased with the distance from hedgerows. This is consistent with several studies that highlighted an increase in auxiliary abundance (e.g., in parasitoid wasps and ground beetles; Morandin et al., 2014; Theves and Zebitz, 2012) and diversity (e.g., in spiders and ground beetles; Diehl et al., 2013; Theves and Zebitz, 2012), of the ratio of auxiliary to pest insects (e.g., Pisani Gareau et al., 2013) and of pest predation (e.g., in ants, wasps and spiders; Otieno et al., 2023) at the proximity of hedgerows or fallows. This overall observation seems consistent given the greater expected hedgerow complexity and availability of ecological niches, as previously mentioned. Given that insect predation includes pest predation, it can also be assumed to be an agroecological service. Nevertheless, beneficial insects such as pollinators, parasites, or other predators could eventually be predated by the former.

Also, the aphid breeding/nectar thief (dis)service was lower at short distances, particularly 0 m, from hedgerows and in shrubby compared to arboreal hedgerows. Regarding the distance gradient, our main explanation is that the higher insect predation at short distance from hedgerows, as already discussed, impede ant/aphid mutualism. Given that aphid presence is of primary concern from an agricultural perspective, we searched for studies conducted in comparable agricultural contexts. In line with our observations, Morandin et al. (2014) and Stutz and Entling (2011) reported reduced aphid abundance in fields adjacent to hedgerows. Furthermore, Diehl et al. (2013) found a decrease in aphid abundance linked to vegetal structure complexification. This vegetal structure complexification may explain in two different, but not incompatible, ways the lower presence of aphids near hedgerows: it can enhance insect predation and/or reduce the availability of suitable ecological niches for aphids.

We hypothesize that insect predators inhabiting shrubby hedgerows (ants and others) may exhibit greater functional compatibility with the adjacent agricultural environment compared to those inhabiting arboreal hedgerows. Specifically, the predators of the latter might be less prone to extend their functional service into the adjacent field interior, at least to a lesser extent than their counterparts in shrubby hedgerows. This remains largely theoretical and warrants verification in future research. However, our study revealed a trend at 0 m, indicating stronger ant predation associated with arboreal hedgerows, consistent with enhanced insect predation services with increasing vegetation structural complexity (Fig. A3o). This difference decreased by 6 m and even reversed beyond 12 m, favoring shrubby hedgerows. This later observation aligns with a greater functional compatibility between organisms providing insect predation services and the adjacent agricultural field in the case of shrubby hedgerows, potentially impeding aphid breeding. Eventually, we assume that aphid breeding/nectar thief, by favoring the presence and abundance of insects frequently assimilated as pests, could be interpreted as an agroecological disservice.

Our study emphasizes that hedgerows and their associated biodiversity must enhance and reduce ecosystem agroecological services and disservices, respectively. However, we wish to highlight the fact that biodiversity does not solely contribute to ecosystem services but also disservices (Zhang et al., 2007) and that the classification of a biological process as a service or disservice depends on the context, as discussed in this study, particularly for soil tilling. While the concept of biodiversity providing ecosystem services is widely studied and promoted, it is often an oversimplified and inaccurate portrayal of reality (Blanco et al., 2019). We argue that framing biodiversity solely in terms of its ecosystem service benefits can be counterproductive, especially when attempting to defend biodiversity, such as in agricultural contexts. Overlooking (or sometimes obscuring) this more complex reality may actually backfire. For instance, stakeholders within the system, such as farmers, may feel misled or that their concerns are misunderstood, leading them to dismiss the conversation altogether.

Ants, as recognized ecosystem engineers, play key roles in agroecosystem functioning, influencing both ecosystem services and disservices. In this study, we observed a clear impact of hedgerow proximity on ant communities, both from taxonomic and functional perspectives. Beyond a slight increase in species richness, our results reveal that ant community composition near hedgerows is distinct from those further away, resulting in higher functional diversity closer to these ecological infrastructures. At a local scale, hedgerows appear to support and maintain both taxonomic and functional diversity within agricultural landscapes. Moreover, for the first time to our knowledge, shrubby and arboreal hedgerows were compared for ant communities, notably showing that arboreal hedgerows have greater species richness and functional dispersion.

There is growing scientific evidence that hedgerows serve as valuable agroecological infrastructures, enhancing biodiversity from an ecological perspective and improving system resilience from an agronomic viewpoint. Our study both confirms and completes this evidence from a taxonomic and functional perspective but also for agroecological (dis)services regarding the increase in presumed services (i.e., soil tilling and insect predation) and the decrease in presumed disservices (i.e., aphid breeding/nectar thief), the latter being even lower in shrubby hedgerows. These agronomic services and disservices are essential for understanding agroecosystem functioning, and to promote trust between academics and farmers, we advise the latter to provide the former with an unbiased vision of the system they are part of.

Our study primarily focused on the effects of different types of hedgerows on ant communities at short (< 50 m) distances, where relative impacts on crop productivity are believed to occur. Future research could extend our investigation to assess the influence of hedgerows on other taxa and over larger distances within agricultural landscapes. Such studies could be particularly informative in degraded bocage or open-field landscapes and could contribute to the development of more effective agroecological management plans. We also encourage future studies to follow the recommendations on pitfall traps provided by Brown and Matthews (2016), particularly the standardization of trap design and the inclusion of a system to prevent vertebrate bycatch. Coupled with this study, future research will offer insights into designing and manage French agricultural landscapes to optimize both biodiversity conservation and agricultural productivity.

Table A1Variables considered in the present study, their type and unit, and if and how they were analyzed.

Table A2Simplified taxonomy of the sampled ant species (Formicidae). The Descriptor column presents the species reference description according to the admitted international nomenclature.

Table A3Results of the Kruskal–Wallis analyses conducted for the species occurrences. We present the Kruskal–Wallis χ2 statistics along with the significance levels of the pvalues indicated as follows: • < 0.06, ∗ < 0.05, < 0.01, < 0.001. Values are rounded to three decimal places (0.001) and set in bold when statistically significant.

Figure A1Scatterplot showing the distribution of the qualitative variables used in the multiple correspondence analysis (MCA). Type refers to the hedgerow type. Adjacent land culture indicates the crop of the adjacent agricultural plot. Adjacent land slope direction was categorized as “Perpendicular”, “Parallel”, “Flat” (no slope), or “None”, the latter when the slope direction was not clearly perpendicular or parallel to the hedgerow. Orientation refers to the cardinal orientation of the hedgerow: “S” for south, “N” for north, “E” for east and “W” for west.

Figure A2Principal component analysis (PCA): (a) plot of hedgerows variables, (b) biplot of hedgerows according to their type (arboreal in dark green, shrubby in light green); Dim1 – principal component 1; Dim2 – principal component 2.

Figure A3Distribution (violin plots and associated boxplots) of the parameters for which GLM and Kruskal–Wallis analyses were significant, regarding the distance (m) from and type of hedgerows. (a) Species richness, (b) functional dispersion, (c) functional mean nearest neighbor distance and (d) functional evenness indices. Hedgerow type was coded as shrubby (light green) and arboreal (dark green). The dashed line at zero, in cases where the distribution includes negative values, serves as a reminder that these values are not realistic but remain consistent with the predicted dispersal indicator.

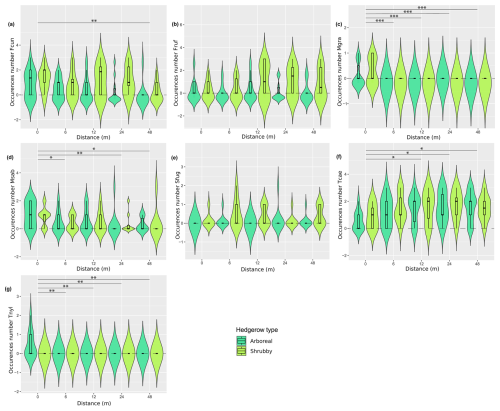

Figure A4Distribution (violin plots and associated boxplots) of the occurrence number of several species, for which Kruskal–Wallis tests were significant, regarding the distance (m) from and type of hedgerows. (a) Formica cunicularia, (b) F. rufibarbis, (c) Myrmecina graminicola, (d) Myrmica specioides, (e) Solenopsis fugax, (f) Tetramorium grp. caespitum-impurum and (g) Temnothorax nylanderi. Hedgerow type was coded as shrubby (light green) and arboreal (dark green). The dashed line at zero, in cases where the distribution includes negative values, serves as a reminder that these values are not realistic but remain consistent with the predicted dispersal indicator.

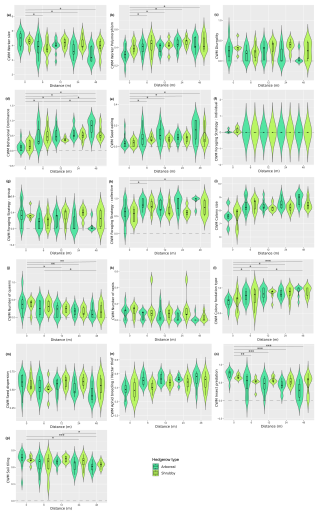

Figure A5Distribution (violin plots and associated boxplots) of the community-weighted means for which GLM and Kruskal–Wallis analyses were significant regarding the distance (m) from and type of hedgerows. (a) Worker size, (b) worker polymorphism, (c) diurnality, (d) behavioral dominance, (e) seed eating, (f) individual foraging strategy, (g) group foraging strategy, (h) collective foraging strategy, (i) colony size, (j) number of queens, (k) number of nests, (l) colony foundation type, (m) seed dispersion, (n) aphid breeding/nectar thief, (o) insect predation and (p) soil tilling. Hedgerow type was coded as shrubby (light green) and arboreal (dark green). The dashed line at zero, in cases where the distribution includes negative values, serves as a reminder that these values are not realistic but remain consistent with the predicted dispersal indicator.

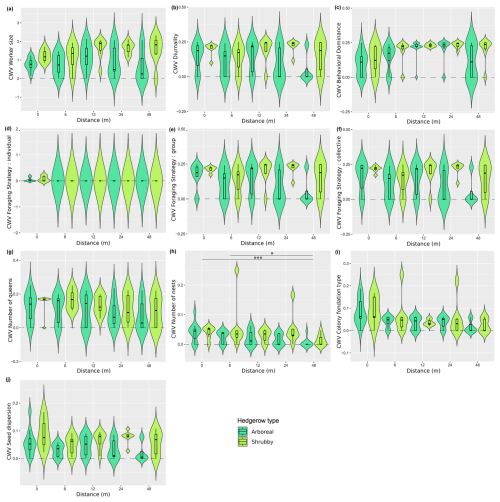

Figure A6Distribution (violin plots and associated boxplots) of the community-weighted variances for which Kruskal–Wallis tests were significant regarding the distance (m) from and type of hedgerows. (a) Worker size, (b) diurnality, (c) behavioral dominance, (d) individual foraging strategy, (e) group foraging strategy, (f) collective foraging strategy, (g) number of queens, (h) number of nests, (i) colony foundation type and (j) seed dispersion. Hedgerow type was coded as shrubby (light green) and arboreal (dark green). The dashed line at zero, in cases where the distribution includes negative values, serves as a reminder that these values are not realistic but remain consistent with the predicted dispersal indicator.

Raw data set is available in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplement and code is available upon reasonable request to the authors.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/we-26-1-2026-supplement.

The research project protocol was conceived by GJ (lead), with significant contributions from CM and TJ. The research project analyses were conceptualized by CM and TJ (lead), with additional contributions from GJ. Field biological sampling was conducted equally by CM, TJ and GJ. Ant identification was led by CM and TJ, with additional contributions from GJ. CM and TJ structured and analyzed the data. The paper was drafted by CM and TJ (lead), with further contributions from GJ. All authors contributed to editing the article and approved the final version.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors.

We express our gratitude to several colleagues from the University of Montpellier, who provided significant support throughout the study. Their assistance in conceptualizing the research, conducting fieldwork, sorting specimens, identifying ants and refining the article was greatly appreciated. Special thanks go to Roland Godon, Timothée Chenin and Simon Mazaud for their contributions.

We are also grateful to Rumsais Blatrix (CEFE Laboratory, Montpellier) and Fabien Leprieur (MARBEC Laboratory, Montpellier) for their expertise and guidance, particularly in ant identification, statistical analyses, and the overall development and writing of this article.

Special thanks are extended to Todd and Marie-Lise Johnson for graciously providing us with accommodation during fieldwork.

We sincerely thank the Department of Biology and Ecology at the Faculty of Sciences of the University of Montpellier for lending us the stereo microscopes used for ant identification.

We wish to acknowledge Christophe Galkowski for his expertise in confirming the morphological identification of Tetramorium moravicum specimens.

Additionally, we are indebted to the Maymat Medical Laboratory of Moulins for generously supplying a substantial quantity of sterile sampling tubes.

We extend our thanks to Andrea Reyes C. for her assistance in improving the English quality of the present article.

We are grateful to the farmers, Pierre and Paul de Gallard, who welcomed us warmly and granted access to their properties for sampling during our fieldwork.

Finally, we would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive remarks throughout article revision.

This paper was edited by Daniel Montesinos and reviewed by three anonymous referees.

Aberlenc, H.-P., CIRAD-BIOS-UMR, and CBGP: Les insectes du monde – Biodiversité, classification, clés de détermination des familles, Quae., 1848 pp., ISBN 978-2-37375-101-7, 2021.

Aguiar, A. P., Deans, A. R., Engel, M. S., Forshage, M., Huber, J. T., Jennings, J. T., Johnson, N. F., Lelej, A. S., Longino, J. T., Lohrmann, V., Mikó, I., Ohl, M., Rasmussen, C., Taeger, A., and Yu, D. S. K.: Order Hymenoptera, in: Animal Biodiversity: An Outline of Higher-level Classification and Survey of Taxonomic Richness (Addenda 2013), edited by: Zhang, Z.-Q., Zootaxa, 3703, 51–62, https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3703.1.12, 2013.

Albrecht, M., Kleijn, D., Williams, N. M., Tschumi, M., Blaauw, B. R., Bommarco, R., Campbell, A. J., Dainese, M., Drummond, F. A., Entling, M. H., Ganser, D., Arjen de Groot, G., Goulson, D., Grab, H., Hamilton, H., Herzog, F., Isaacs, R., Jacot, K., Jeanneret, P., Jonsson, M., Knop, E., Kremen, C., Landis, D. A., Loeb, G. M., Marini, L., McKerchar, M., Morandin, L., Pfister, S. C., Potts, S. G., Rundlöf, M., Sardiñas, H., Sciligo, A., Thies, C., Tscharntke, T., Venturini, E., Veromann, E., Vollhardt, I. M. G., Wäckers, F., Ward, K., Westbury, D. B., Wilby, A., Woltz, M., Wratten, S., and Sutter, L.: The effectiveness of flower strips and hedgerows on pest control, pollination services and crop yield: a quantitative synthesis, Ecol. Lett., 23, 1488–1498, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.13576, 2020.

Alignier, A., Uroy, L., and Aviron, S.: The role of hedgerows in supporting biodiversity and other ecosystem services in intensively managed agricultural landscapes, in: Reconciling agricultural production with biodiversity conservation, Burleigh Dodds Science Publishing, ISBN 978-1-003-04792-6, 2020.

Andersen, A. N.: A Classification of Australian Ant Communities, Based on Functional Groups Which Parallel Plant Life-Forms in Relation to Stress and Disturbance, J. Biogeogr., 15, https://doi.org/10.2307/2846070, 1995.

Andersen, A. N.: Functional groups and patterns of organization in North American ant communities: a comparison with Australia, J. Biogeogr., 24, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.1997.00137.x, 1997.

Andersen, A. N. and Majer, J. D.: Ants show the way Down Under: invertebrates as bioindicators in land management, Front. Ecol. Environ., 2, 291–298, https://doi.org/10.1890/1540-9295(2004)002[0292:astwdu]2.0.co;2, 2004.

Angel, M., Glachant, M., and Lévèque, F.: La préservation des espèces: que peuvent dire les économistes?, Economie et statistique, https://doi.org/10.3406/estat.1992.6562, 1992.

Aoun, R.: An overview of the French landscape characteristics and dynamics on a national level, Tájökológiai Lapok, 8, 89–98, https://doi.org/10.56617/tl.4052, 2010.

Arnan, X., Cerdá, X., and Retana, J.: Ant functional responses along environmental gradients, J. Anim. Ecol., 83, 1398–1408, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2656.12227, 2014.

Arnan, X., Cerdá, X., and Retana, J.: Relationships among taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic ant diversity across the biogeographic regions of Europe, Ecography, 40, 448–457, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01938, 2017.

Baraibar, B., Westerman, P. R., Carrión, E., and Recasens, J.: Effects of tillage and irrigation in cereal fields on weed seed removal by seed predators, J. Appl. Ecol., 46, 380–387, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01614.x, 2009.

Baraibar, B., Carrión, E., Recasens, J., and Westerman, P. R.: Unravelling the process of weed seed predation: Developing options for better weed control, Biol. Control, 56, 85–90, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocontrol.2010.09.010, 2011.

Barr, C. J., Britt, C. P., Sparks, T. H., and Churchward, T. H.: Hedgerow management and wildlife: A review of research on the effects of hedgerow management and adjacent land on biodiversity, Adas, Barr ecology ltd, CEH, 2005.

Baudry, J. and Jouin, A.: De la haie aux bocages: organisation, dynamique et gestion, Institut national de la recherche agronomique, Paris, ISBN 978-2-7380-1050-6, 2003.

Blanco, J., Dendoncker, N., Barnaud, C., and Sirami, C.: Ecosystem disservices matter: Towards their systematic integration within ecosystem service research and policy, Ecosyst. Serv., 36, 100913, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoser.2019.100913, 2019.

Boinot, S., Alignier, A., Aviron, S., Bertrand, C., Cheviron, N., Comment, G., Jeavons, E., Le Lann, C., Mondy, S., Mougin, C., Précigout, P.-A., Ricono, C., Robert, C., Saias, G., Vandenkoornhuyse, P., and Mony, C.: Organic farming and semi-natural habitats for multifunctional agriculture: A case study in hedgerow landscapes of Brittany, J. Appl. Ecol., 1–11, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.14825, 2024.

Boutin, C., Jobin, B., Bélanger, L., and Choinière, L.: Plant diversity in three types of hedgerows adjacent to cropfields, Biodivers. Conserv., 11, 1–25, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014023326658, 2002.

Brown, G. R. and Matthews, I. M.: A review of extensive variation in the design of pitfall traps and a proposal for a standard pitfall trap design for monitoring ground-active arthropod biodiversity, Ecol. Evol., 6, 3953–3964, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.2176, 2016.

Burel, F., Baudry, J., Butet, A., Clergeau, P., Delettre, Y. R., Le Coeur, D., Dubs, F., Morvan, N., Paillat, G., Petit, S., Thenail, C., Brunel, E., and Lefeuvre, J.-C.: Comparative biodiversity along a gradient of agricultural landscapes, Acta Oecologica, 19, 47–60, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1146-609X(98)80007-6, 1998.

Burel, F., Butet, A., Delettre, Y. R., and Millàn de la Peña, N.: Differential response of selected taxa to landscape context and agricultural intensification, Landsc. Urban Plan., 67, 195–204, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-2046(03)00039-2, 2004.

Carmona, C. P., Guerrero, I., Peco, B., Morales, M. B., Oñate, J. J., Pärt, T., Tscharntke, T., Liira, J., Aavik, T., Emmerson, M., Berendse, F., Ceryngier, P., Bretagnolle, V., Weisser, W. W., and Bengtsson, J.: Agriculture intensification reduces plant taxonomic and functional diversity across European arable systems, Funct. Ecol., 34, 1448–1460, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.13608, 2020.

Carvalho, R. L., Andersen, A. N., Anjos, D. V., Pacheco, R., Chagas, L., and Vasconcelos, H. L.: Understanding what bioindicators are actually indicating: Linking disturbance responses to ecological traits of dung beetles and ants, Ecol. Indic., 108, 105764, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105764, 2020.

Chouquer, G.: Annie Antoine, Le paysage de l'historien. Archéologie des bocages de l'ouest de la France à l'époque moderne, Études Rural., 321–323, https://doi.org/10.4000/etudesrurales.2964, 2003.

Colwell, R. K., Chao, A., Gotelli, N. J., Lin, S.-Y., Mao, C. X., Chazdon, R. L., and Longino, J. T.: Models and estimators linking individual-based and sample-based rarefaction, extrapolation and comparison of assemblages, J. Plant Ecol., 5, 3–21, https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtr044, 2012.

Crist, T.: Biodiversity, species interactions, and functional roles of ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in fragmented landscapes: a review, Myrmecol. News, 12, 3–13, 2009.

Dauber, J. and Wolters, V.: Edge effects on ant community structure and species richness in an agricultural landscape, Biodivers. Conserv., 13, 901–915, https://doi.org/10.1023/B:BIOC.0000014460.65462.2b, 2004.

David, C. and Keith, A.: A comparative study of the invertebrate faunas of hedgerows of differing ages, with particular reference to indicators of ancient woodland and “old growth”, J. Pract. Ecol. Conserv., 8, ISSN 1354-0270, 2009.

Diehl, E., Mader, V. L., Wolters, V., and Birkhofer, K.: Management intensity and vegetation complexity affect web-building spiders and their prey, Oecologia, 173, 579–589, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-013-2634-7, 2013.

Dover, J. W.: The Ecology of Hedgerows and Field Margins, Routledge, 307 pp., ISBN 978-1-351-35550-6, 2019.

Dudley, N. and Alexander, S.: Agriculture and biodiversity: a review, Biodiversity, 18, 45–49, https://doi.org/10.1080/14888386.2017.1351892, 2017.

Duelli, P. and Obrist, M. K.: In search of the best correlates for local organismal biodiversity in cultivated areas, Biodivers. Conserv., 7, 297–309, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008873510817, 1998.

European Commission: La PAC en bref – Commission européenne, 2023.

FAO: Land use in agriculture by the numbers, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2020.

Folgarait, P. J.: Ant biodiversity and its relationship to ecosystem functioning: a review, Biodivers. Conserv., 7, 1221–1244, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008891901953, 1998.

French Biodiversity Agency: Haies et bocages: des réservoirs de biodiversité, Office Français pour la Biodiversité (OFB), 2024.

French Ministry of Agriculture and Food Sovereignty: Recensement agricole 2020, 2022.

Frouz, J. and Jílková, V.: The effect of ants on soil properties and processes (Hymenoptera: Formicidae), Myrmecol. News Myrmecol News, 11, 191–199, 2008.

Gallé, R., Happe, A.-K., Baillod, A. B., Tscharntke, T., and Batáry, P.: Landscape configuration, organic management, and within-field position drive functional diversity of spiders and carabids, J. Appl. Ecol., 56, 63–72, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13257, 2019.

García de León, D., Rey Benayas, J. M., and Andivia, E.: Contributions of Hedgerows to People: A Global Meta-Analysis, Front. Conserv. Sci., 2, ISSN 2673-611X, 2021.

García-Navas, V., Martínez-Núñez, C., Tarifa, R., Manzaneda, A. J., Valera, F., Salido, T., Camacho, F. M., Isla, J., and Rey, P. J.: Agricultural extensification enhances functional diversity but not phylogenetic diversity in Mediterranean olive groves: A case study with ant and bird communities, Agric. Ecosyst. Environ., 324, 107708, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2021.107708, 2022.

Garon, D., Guéguen, J.-C., and Rioult, J.-P.: Biodiversité et évolution du monde vivant, EDP Sciences, https://doi.org/10.1051/978-2-7598-1086-4, 2013.

Gómez, C. and Espadaler, X.: An update of the world survey of myrmecochorous dispersal distances, Ecography, 36, 1193–1201, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.00289.x, 2013.

Gómez, C., Espadaler, X., and Bas, J. M.: Ant behaviour and seed morphology: a missing link of myrmecochory, Oecologia, 146, 244–246, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-005-0200-7, 2005.

Gorb, S. N. and Gorb, E. V.: Effects of Ant Species Composition on Seed Removal in Deciduous Forest in Eastern Europe, Oikos, 84, 110–118, https://doi.org/10.2307/3546871, 1999.

Gordon, D. M.: The development of an ant colony's foraging range, Anim. Behav., 49, 649–659, https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-3472(95)80198-7, 1995.

Gotelli, N. J., Ellison, A. M., Dunn, R. R., and Sanders, N. J.: Counting ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae): biodiversity sampling and statistical analysis for myrmecologists, Myrmecol. News, 15, 13–19, 2011.

Handel, S. N. and Beattie, A. J.: Seed Dispersal by Ants, Sci. Am., 263, 76-83B, 1990.

Holland, J. M., Douma, J. C., Crowley, L., James, L., Kor, L., Stevenson, D. R. W., and Smith, B. M.: Semi-natural habitats support biological control, pollination and soil conservation in Europe. A review, Agron. Sustain. Dev., 37, 31, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13593-017-0434-x, 2017.

Hombegowda, H. C., Adhikary, P. P., Jakhar, P., Madhu, M., and Barman, D.: Hedge row intercropping impact on run-off, soil erosion, carbon sequestration and millet yield, Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosystems, 116, 103–116, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10705-019-10031-2, 2020.

Hothorn, T., Zeileis, A., Farebrother, R. W., Cummins, C., Millo, G., and Mitchell, D.: lmtest: Testing Linear Regression Models, 2022.

Hsieh, T. C. and Chao, K. H. M. A.: iNEXT: Interpolation and Extrapolation for Species Diversity, 2022.

Jahnová, Z., Knapp, M., Boháč, J., and Tulachová, M.: The role of various meadow margin types in shaping carabid and staphylinid beetle assemblages (Coleoptera: Carabidae, Staphylinidae) in meadow dominated landscapes, J. Insect Conserv., 20, 59–69, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-015-9839-5, 2016.

Kark, S.: Effects of Ecotones on Biodiversity, in: Encyclopedia of Biodiversity, Elsevier, 142–148, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-384719-5.00234-3, 2013.

Kassambara, A. and Mundt, F.: factoextra: Extract and Visualize the Results of Multivariate Data Analyses, https://doi.org/10.32614/cran.package.factoextra, 2020.

Kratschmer, S., Hauer, J., Zaller, J. G., Dürr, A., and Weninger, T.: Hedgerow structural diversity is key to promoting biodiversity and ecosystem services: A systematic review of Central European studies, Basic Appl. Ecol., 78, 28–38, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.baae.2024.04.010, 2024.

Kreider, J. J., Chen, T.-W., Hartke, T. R., Buchori, D., Hidayat, P., Nazarreta, R., Scheu, S., and Drescher, J.: Rainforest conversion to monocultures favors generalist ants with large colonies, Ecosphere, 12, e03717, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.3717, 2021.

Kubiak, K. L., Pereira, J. A., Tessaro, D., Santos, S. A. P., and Benhadi-Marín, J.: Functional diversity of epigeal spiders in the olive grove agroecosystem in northeastern Portugal: a comparison between crop and surrounding semi-natural habitats, Entomol. Exp. Appl., 170, 449–458, https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.13162, 2022.

Lê, S., Josse, J., and Husson, F.: FactoMineR: An R Package for Multivariate Analysis, J. Stat. Softw., 25, 1–18, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v025.i01, 2008.

Lebas, C., Galkowski, C., Blatrix, R., and Wegnez, P.: Fourmis d'Europe occidentale, Delachaux et Niestlé, Paris, 416 pp., ISBN 978-2-603-02430-0, 2016.

Lobry de Bruyn, L. A.: Ants as bioindicators of soil function in rural environments, in: Invertebrate Biodiversity as Bioindicators of Sustainable Landscapes, Elsevier, 425–441, https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-444-50019-9.50024-8, 1999.

MacArthur, R. H. and MacArthur, J. W.: On Bird Species Diversity, Ecology, 42, 594–598, https://doi.org/10.2307/1932254, 1961.

MacArthur, R. H. and Wilson, E. O.: The Theory of Island Biogeography, Princeton University Press, 226 pp., ISBN 9780691088365, 2001.

Magneville, C., Loiseau, N., Albouy, C., Casajus, N., Claverie, T., Escalas, A., Leprieur, F., Maire, E., Mouillot, D., and Villéger, S.: mFD: an R package to compute and illustrate the multiple facets of functional diversity, Ecography, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05904, 2022.

Majer, J. D.: Ants: Bio-indicators of minesite rehabilitation, land-use, and land conservation, Environ. Manage., 7, 375–383, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01866920, 1983.

Mangiafico, S.: rcompanion: Functions to Support Extension Education Program Evaluation, 2025.

Markó, B., Ionescu-Hirsch, A., and Anna-Maria, S.-L.: Genus Camponotus Mayr, 1861 (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Romania: distribution and identification key to the worker caste, Entomol. Romanica, 14, 29–41, 2009.

McCravy, K. W.: A Review of Sampling and Monitoring Methods for Beneficial Arthropods in Agroecosystems, Insects, 9, 170, https://doi.org/10.3390/insects9040170, 2018.