the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

The Rings of Power: managing nutrient cycles in aquatic food webs above and beyond primary producers

Jan Mraz

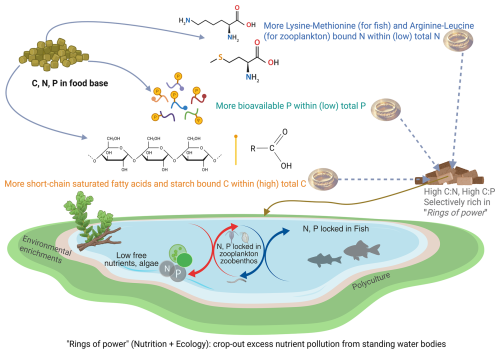

Global nutrient cycles (biogeochemical flows of nitrogen and phosphorus; N, P) are at a tipping point. In aquatic systems, natural food webs facilitate nutrient digestion and decomposition, but nutrient assimilation is poor. The current approach to understanding and managing nutrient cycles in aquatic systems needs to integrate animal nutritionist thinking. It is not the supply or stoichiometry of elements (carbon (C), N, P) in the food web but the supply and stoichiometry of specific biomolecular packages in which they come (aka Rings of Power) that decides the state of nutrient cycles (slow/fast, low/high) in all trophic levels above primary producers. Animal nutritionists often maximize N and P retention efficiency in animal production systems by expanding the scope of homeostatic control of nutrient deposition in animals. By spiking specific biomolecular packages in the diet (e.g., Rings of Power, such as specific amino acids, lipid classes, carbohydrate subfractions like starch), it is possible to alleviate energy–nutrient transfer barriers from food to biomass. Under the influence of “Rings of Power”, free N and P excretion is minimized and protein (N-bound), phospholipid, and apatite-rich (P-bound) biomass is maximized. Combining such expertise with food web (plankton) ecology, we can develop nature-based, regenerative aquaculture solutions in hypertrophic inland standing waterbodies (which accumulate nutrients) to slow down N and P cycles by curbing the metabolic N and P throughput of consumer communities (omnivorous fish, zooplankton) and suppress eutrophication.

- Article

(2217 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Global nutrient cycles are at a tipping point. We are already overshooting Earth's safe operating space (planetary health boundaries) for carbon (C; climate change), nitrogen, and phosphorus flows (N and P; biogeochemical cycling) (Steffen et al., 2015; Richardson et al., 2023). To slow down or restrict nutrient cycles, the current approach to understanding and managing eutrophication processes in diverse ecosystems (Elser et al., 2007) needs an urgent integration of animal nutritionist thinking. Elements and elemental ratios are used across trophic levels to understand and manipulate nutrient cycles in terrestrial and aquatic food webs. Ecologists concern themselves with elements (e.g., C, N, P) and elemental ratios (e.g., the Redfield ratio, ecological stoichiometry theory) across trophic levels and predator–prey/consumer–producer interactions to understand nutrient cycles in our global food web (Sterner and Elser, 2003).

To some extent, it is valid up to the primary producers' trophic level, but not beyond. Our biosphere is not composed solely of primary producers; it also includes consumers. To restrain global nutrient cycles (C, N, P) from tipping points, the general focus on and reductionist approach to the elements C, N, and P have limitations. The supply–demand relationships of elemental C, N, and P are straightforward for plants, fungi, and protists that require these elements for biomass accretion. The more fertilization of these elements in free forms, the greater their response to growth. However, animals do not grow on free forms of elemental C, N, and P, and the supply–demand relationships of elemental C, N, and P are not straightforward for animal systems. For example, in fish, the mean effect size of diet elemental proportion (N : P) on excretion N : P was not significantly different from 0 (meaning no effect) in either diet manipulation studies or field surveys (Moody et al., 2015). Seeing this, it was hypothesized that testing stoichiometric theory might require that future work examining dietary effects on excretion rates and ratios considers not only dietary N : P ratios but also the forms in which these nutrients are present (Moody et al., 2015). Therefore, a re-focus is necessary on the various packaging(s) or biomolecular forms of these elements, in which C, N, and P are available to consumers from the resource pool (food web). One can supply the same amount of nitrogen to fish mainly via non-essential amino acids, while the other can supply mainly via essential amino acids, rendering the growth response higher in the latter (Peres and Oliva-Teles, 2006). Similarly, one can supply more carbon to fish through a high-protein diet or through non-protein fractions (lipids, carbohydrates) on an isoenergetic intake basis; the growth response would be higher in the latter (Heinitz et al., 2018). One can supply the same amount of phosphorus to fish, but with low and high background levels of essential-amino-acid-bound N or low and high levels of non-protein-bound C fractions, the phosphorus storage is always low under the “low” supplies of key biomolecular packages (Roy et al., 2024a; Ruohonen et al., 1999). These interactions in animal systems are overlooked, and a generalist focus on elements only (quantity × stoichiometry) in the “animal-type” food web makes it redundant. Not all C, N, or P is equal in animal systems or their food webs; mathematically, we keep treating those data as if they were equal, but their biomolecular packaging matters a lot. For example, essential-amino-acid-bound N or non-protein-bound C (that is digestible and not a fiber) should have more weightage or be disentangled from the total N or total C measured in the food or body. Such a weighting or disentangling approach is not often seen in food web ecology (C, N, P flow) calculations. It is well realized that it is time to look beyond C : N : P (Van de Waal et al., 2018) and that animal nutritionists are necessary in ecology.

Ecology and nutrition are two discrete fields that rarely interact. So far, ecologists have taken the lead in bridging the nutrition gap. Limited interdisciplinary relationships have resulted in seminal biochemical views of the food web (Müller-Navarra, 2008; Ruess and Müller-Navarra, 2019), bridging nutritional geometry with ecological stoichiometry theory (Sperfeld et al., 2017; Meunier et al., 2017) and contemplating nutrient form/quality over quantity (Danger et al., 2022; Müller-Navarra and Ruess, 2019). So far, while bridging nutrition and ecology (by ecologists), too much emphasis has been on viewing one biomolecule at a time, rather than on their proportions relative to other biomolecules or metabolizable energy. For example, there is an overemphasis on fatty acids in the aquatic food web, while amino acids are discussed negligibly. Also, biomolecule groups in the food web (e.g., lipids) are often discussed alone, not considering complex bioenergetics principles such as protein- and lipid-sparing effects, protein quality for tissue synthesis, or what mitochondria prefer as easy metabolic fuel (e.g., starch, saturated fatty acids) and what is too complex to burn as metabolic fuel (e.g., long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids).

Plants, or primary producers, need elements (N, C, and P) (Parent et al., 2013), while animals, or consumers, require biomolecules such as proteins, carbohydrates/lipids, and phospholipids/non-apatite P as sources of those elements, respectively. The trophic levels above primary producers have lost half of their amino acid synthesis or nitrogen re-packing capabilities (e.g., essential amino acids) (Jennings, 1972; Wu, 2017). Unlike primary producers, consumers cannot reflect the elemental composition of their food base in their bodies, due to homeostatic control (Van de Waal and Boersma, 2012). Consumers cannot use photonic energy to synthesize and store matter from absorbed elements (e.g., the photosynthesis principle); instead, they need a combination of metabolic energy and catabolism first to be able to synthesize and store new matter (e.g., the nutritional bioenergetics principle) (Bureau et al., 2003). Also, the fates of C, N, and P in consumers in terrestrial and aquatic food webs, whether released from or retained in the body, are dictated by a handful of key biomolecules containing such elements. The minimum requirement of those key biomolecules (e.g., essential amino acids, long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids, cholesterol, phospholipids) changes relative to the availability of energy from non-key biomolecules. Surplus energy provided by dietary non-key biomolecules (e.g., non-essential amino acids, starch, glycogen, and saturated or monounsaturated fats) lowers the requirement of dietary key biomolecules, and more of dietary C, N, and P could remain trapped in the body of consumers. While inadequate energy from non-key biomolecules increases the need for and catabolism (destruction) of key biomolecules to supply energy, more C, N, and P could be released from consumers' bodies due to a loss of nutritional bioenergetic efficiency. The fundamentals of nutrient ingestion–excretion cycles in the animal body are better understood by nutritionists, who strive to provide a balanced diet or nutrition optimized for bioenergetics. Aquatic animal nutritionists concern themselves with a wider set of biomolecules (not elements) and biomolecule ratios (e.g., amino acids, fatty acids, starch/glycogen, energy profiles) across digestive and metabolic axes to understand C, N, and P cycles (retention, excretion) (Roy et al., 2022, 2023, 2024a; Kaushik and Seiliez, 2010; Bureau et al., 2003; Kaushik and Schrama, 2022; Heinitz et al., 2018; Ruohonen et al., 1999; Kaushik et al., 1995; Kim and Kaushik, 1992; Watanabe et al., 1987). In nature, we now understand that the natural food web helps digest nutrients (Roy et al., 2024c). However, metabolic assimilation is rather poorly constrained by stoichiometric errors and consumer homeostasis in an imbalanced diet (Roy et al., 2022, 2024a, b; Mraz et al., 2025). It is, by nature, a deliberate error to keep primary productivity running on free nutrients leaked/spilled by consumers. Nutritionists have been able to address those natural flaws while understanding physiology and fulfilling the commercial interests of animal production science. Thanks to that, we are now farming animals at much lower nutritional requirements and maximized digestible and metabolic nutrient use efficiencies (e.g., poultry, fish, pig) than what they used to be in the past (Kaushik and Schrama, 2022; Kim et al., 2019; You et al., 2024; Turchini et al., 2019; Glencross et al., 2023). It is not the elemental C, N, or P that ecologists traditionally see, but specific biomolecules (aka rings) that ecologists can use to understand C, N, and P flows (or even manage C, N, and P cycles) in ecosystems. It is not the C, N, or P in the food web but the package in which they come (aka Rings of Power) to animal systems that decides the fate of nutrient cycles in higher trophic levels (Roy et al., 2022; Roy et al., 2024a). Total N in seston or algae may be meaningless for zooplankton or fish food web calculations; it is the essential-amino-acid-bound N that matters. Likewise, total C in seston or algae could be meaningless for zooplankton or fish; it is the non-protein-fraction-bound C that is easily assimilated (and not part of fibers/non-starch polysaccharides, polyunsaturated fatty acids, or cholesterol) that matters. Total P in seston or algae could also be meaningless, as the non-apatite-, non-phytate-, and phospholipid-bound P is what matters for zooplankton or fish. For example, rings of power for fish and crustaceans (including zooplankton) in aquatic systems could be ratios of starch/glycogen–fatty acid–cholesterol-bound C, lysine–methionine–arginine-bound N, and phospholipid-bound P or orthophosphates in water absorbed by integuments. Even for terrestrial mammals or humans, the rings of power could be ratios of starch–triglyceride-bound C, leucine-bound N, and organic P in food. Here, it is important to note that nutritionists emphasize not the quantity alone, but the relative proportion of these rings of power that rule the Liebig's law of the minimum in animal systems (Konnert et al., 2022; Rombenso et al., 2022; Roy et al., 2022, 2023, 2024a). These rings of power, when sufficient, could abolish nutrient–energy transfer barriers between food and the body and suppress nutrient leakage or spillover from the ecosystem's consumers. When these rings of power are insufficient in the food webs, they do the opposite – ecosystems turn into a soup of free nutrients, overshooting primary productivity (but no effect on secondary and tertiary productivity), and the chain of trophic transfer efficiency is broken (“kaput”). The mechanism of rings of power is conceptually described in Fig. 1.

Figure 2Rings of power in action to slow down nutrient flows from tipping points in standing freshwater bodies. By providing “rings-of-power feeds” (e.g., spring-/autumn-time digestible non-protein energy or C-rich feed, summer-time essential-amino-acid- and non-protein-energy-balanced feed), one can periodically stock and harvest fish stocks to remove anthropogenic nutrients loaded into these waterbodies. Detailed specifications of such rings-of-power-spiked aquatic feeds, but low in overall N and P content, can be found elsewhere (Roy et al., 2025).

Recent efforts by fish nutritionists to balance seasonal imbalances or natural stoichiometric errors in aquatic ecosystems are an excellent example of the potential of the rings of power to manage nutrient cycles (Roy et al., 2022; Kabir et al., 2020). For example, nutrients from human settlements, land, runoff, and farming end up in standing water bodies like a shower sink. In contrast, rings of power in aquatic food webs, such as specific amino acids (lysine) and fatty acids (saturated fatty acids), go missing over the vegetative season (Roy et al., 2024b; Mraz et al., 2025), or remain missing throughout the season, e.g. specific carbohydrate (starch/ glycogen) (Roy et al., 2023, 2024a). Their absence impedes the assimilation of nutrients (C, N, P) into the bodies of aquatic consumers (Bureau et al., 2003; Kaushik et al., 1995; Kim and Kaushik, 1992; Roy et al., 2022, 2023, 2024a; Ruohonen et al., 1999; Watanabe et al., 1987). As a result, free nutrient pollution in water and harmful algal blooms may take precedence (Sharitt et al., 2021; Brabrand et al., 1990; Villeger et al., 2012). By designing “stoichiometric feeds” combining principles of ecological stoichiometry theory, ecological plankton modeling (PEG model), and fish nutritional bioenergetics, scientists are turning nutrient pollution into a solution (biomass) (Roy et al., 2025; Kabir et al., 2020). It is possible to control freely available nutrients (N, P) and suppress eutrophication processes (Roy et al., 2022, 2023, 2024a, 2025; Kabir et al., 2020).

It is now known that fish can directly absorb orthophosphateP from water into the body, in addition to P from the dietary pathway (Roy et al., 2024a; Drábiková, 2023; Sarker et al., 2011; Sugiura, 2024). It is also known that fish can retain more N and P per unit of body mass under a balanced diet, under the influences of the rings of power, e.g., lysine–methionine-bound N and digestible “non-protein” energy or C (Heinitz et al., 2018; Kaushik et al., 1995; Kaushik and Seiliez, 2010; Kim and Kaushik, 1992; Roy et al., 2023; Ruohonen et al., 1999; Watanabe et al., 1987). Besides, the planktonic food web, dominated by zooplankton, can keep C, N, and P from being freely available in the water under low fish grazing pressure (Sommer et al., 2012; Fott et al., 1980; Scheffer and van Nes, 2007; Scheffer, 1998). There is an indirect pathway to cause high metabolic satiety of fish stocks and gut fullness via balanced feeds (Holt et al., 1995; Yamamoto et al., 2003; Harter et al., 2015) that relieves some grazing pressure (active gill filtering, not passive) on zooplankton or reduces homing range in search for benthic macrozoobenthos (Mehner et al., 2019; Jurajda et al., 2016; Říha et al., 2026). Besides the effect of nutrition, providing substrates or refugia in water can also enhance consumer biomass, which can further lock in nutrients (Kajgrova et al., 2021; Šetlíková et al., 2024; van Dam et al., 2002).

Given the global problem of eutrophication and the reliance on chemical- or plant/algae/microbial-based remedial measures to abate nutrient pollution (Kakade et al., 2021), the poor metabolic assimilation of C, N, and P in aquatic consumers may also need to be addressed. Combining the above knowledge or pathways, what if we could maximize the overall efficiency of aquatic consumers (zooplankton and fish) to store more C, N, and P in their bodies? By applying stoichiometrically corrective seasonal feeds spiked with the “rings of power”, we can crop out nutrients via fish and plankton harvests. We have thought of such regenerative agriculture before (Newton et al., 2020), but are the “rings of power” a means to realize it? It can be done in focus locations, such as the inland freshwater standing water bodies that naturally collect anthropogenic and agricultural nutrients from the landscape (like the sink of a shower) – converting them from points of pollution into solutions. A conceptual diagram of the approach is shown in Fig. 2. It is time to establish the field of nutritional ecology within educational and research organizations, where animal nutritionists should be trained and tasked with working on applications in ecology.

KR: conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing (original draft, review and editing). JM: resources, validation, writing (review and editing).

The contact author has declared that neither of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Moving concepts: ecological units in different contexts”. It does not belong to a conference.

The authors are very grateful to the editor and reviewer for improving the scientific quality of the article. The figures were made with Biorender premium (license: DE29B5PYCG, KU29B5Q74D).

The authors were financially supported by the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports of the Czech Republic, OP JAK – Aquaculture for Future project (CZ.02.01.01/00/23_021/0012616) for the preparation of the article. The first author acknowledges the funds from WIAS (Wageningen Institute of Animal Sciences) visiting scientist fellowship for supporting a sabbatical stay and access to its resources that helped in conceiving the article.

This paper was edited by Hermann Heilmeier and reviewed by Tomás Marina.

Brabrand, A., Faafeng, B. A., and Nilssen, J. P. M.: Relative importance of phosphorus supply to phytoplankton production – Fish excretion versus external loading, Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, 47, 364–372, https://doi.org/10.1139/f90-038, 1990.

Bureau, D. P., Kaushik, S. J., and Cho, C. Y.: Bioenergetics, Fish Nutrition, 1–59, 2003.

Danger, M., Bec, A., Spitz, J., and Perga, M.-E.: Special issue: Questioning the roles of resources nutritional quality in ecology, Oikos, 2022, e09503, https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.09503, 2022.

Drábiková, L.: Re-thinking phosphorus: The effects of low and high dietary phosphorus on the development of the skeleton in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar, L.), Ghent University, http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-01H1P4W1DSXFJM3YJ3R7JG5W1R (last access: 9 February 2026), 2023.

Elser, J. J., Bracken, M. E. S., Cleland, E. E., Gruner, D. S., Harpole, W. S., Hillebrand, H., Ngai, J. T., Seabloom, E. W., Shurin, J. B., and Smith, J. E.: Global analysis of nitrogen and phosphorus limitation of primary producers in freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems, Ecol. Lett., 10, 1135–1142, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01113.x, 2007.

Fott, J., Pechar, L., and Pražáková, M.: Fish as a factor controlling water quality in ponds, in: Hypertrophic ecosystems, edited by: Barica, J. and Mur, L. C., Springer, 255–261, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-009-9203-0_28, 1980.

Glencross, B., Fracalossi, D. M., Hua, K., Izquierdo, M., Ma, K. S., Overland, M., Robb, D., Roubach, R., Schrama, J., Small, B., Tacon, A., Valente, L. M. P., Viana, M. T., Xie, S. Q., and Yakupityage, A.: Harvesting the benefits of nutritional research to address global challenges in the 21st century, Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 54, 343–363, https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12948, 2023.

Harter, T. S., Heinsbroek, L. T. N., and Schrama, J. W.: The source of dietary non-protein energy affects in vivo protein digestion in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus), Aquaculture Nutrition, 21, 569–577, https://doi.org/10.1111/anu.12185, 2015.

Heinitz, M. C., Silva, C. F., Schulz, C., and Lemme, A.: The effect of varying dietary digestible protein and digestible non-protein energy sources on growth, nutrient utilization efficiencies and body composition of carp (Cyprinus carpio) evaluated with a two-factorial central composite study design, Aquaculture Nutrition, 24, 723–740, https://doi.org/10.1111/anu.12601, 2018.

Holt, S. H., Miller, J. C., Petocz, P., and Farmakalidis, E.: A satiety index of common foods, European Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 49, 675–690, 1995.

Jennings, J.: Essential components of the diet, in: Feeding, digestion and assimilation in animals, Springer, 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-15482-1_1, 1972.

Jurajda, P., Adámek, Z., Roche, K., Mrkvová, M., Starhová, D., Prásek, V., and Zukal, J.: Carp feeding activity and habitat utilisation in relation to supplementary feeding in a semi-intensive aquaculture pond, Aquaculture International, 24, 1627–1640, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-016-0061-6, 2016.

Kabir, K. A., Verdegem, M. C. J., Verreth, J. A. J., Phillips, M. J., and Schrama, J. W.: Dietary non-starch polysaccharides influenced natural food web and fish production in semi-intensive pond culture of Nile tilapia, Aquaculture, 528, 735506, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735506, 2020.

Kajgrova, L., Adamek, Z., Regenda, J., Bauer, C., Stejskal, V., Pecha, O., and Hlavac, D.: Macrozoobenthos assemblage patterns in European carp (Cyprinus carpio) ponds – the importance of emersed macrophyte beds, Knowledge and Management of Aquatic Ecosystems, 9, https://doi.org/10.1051/kmae/2021008, 2021.

Kakade, A., Salama, E. S., Han, H. W., Zheng, Y. Z., Kulshrestha, S., Jalalah, M., Harraz, F. A., Alsareii, S. A., and Li, X. K.: World eutrophic pollution of lake and river: Biotreatment potential and future perspectives, Environ. Technol. Inno., 23, 101604, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eti.2021.101604, 2021.

Kaushik, S. J. and Schrama, J. W.: Chapter 2 – Bioenergetics, in: Fish Nutrition, 4th Edn., edited by: Hardy, R. W. and Kaushik, S. J., Academic Press, 17–55, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-819587-1.00011-2, 2022.

Kaushik, S. J. and Seiliez, I.: Protein and amino acid nutrition and metabolism in fish: current knowledge and future needs, Aquaculture Research, 41, 322–332, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02174.x, 2010.

Kaushik, S., Doudet, T., Médale, F., Aguirre, P., and Blanc, D.: Protein and energy needs for maintenance and growth of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), Journal of Applied Ichthyology, 11, 290–296, 1995.

Kim, J. D. and Kaushik, S. J.: Contribution of Digestible Energy from Carbohydrates and Estimation of Protein-Energy Requirements for Growth of Rainbow-Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), Aquaculture, 106, 161–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/0044-8486(92)90200-5, 1992.

Kim, S. W., Less, J. F., Wang, L., Yan, T., Kiron, V., Kaushik, S. J., and Lei, X. G.: Meeting global feed protein demand: challenge, opportunity, and strategy, Annual Review of Animal Biosciences, 7, 221–243, 2019.

Konnert, G. D. P., Gerrits, W. J. J., Gussekloo, S. W. S., and Schrama, J. W.: Balancing protein and energy in Nile tilapia feeds: A meta-analysis, Reviews in Aquaculture, 14, 1757–1778, https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12671, 2022.

Mehner, T., Rapp, T., Monk, C. T., Beck, M. E., Trudeau, A., Kiljunen, M., Hilt, S., and Arlinghaus, R.: Feeding aquatic ecosystems: whole-lake experimental addition of angler's ground bait strongly affects omnivorous fish despite low contribution to lake carbon budget, Ecosystems, 22, 346–362, 2019.

Meunier, C. L., Boersma, M., El-Sabaawi, R., Halvorson, H. M., Herstoff, E. M., Van de Waal, D. B., Vogt, R. J., and Litchman, E.: From elements to function: toward unifying ecological stoichiometry and trait-based ecology, Frontiers in Environmental Science, 5, 18, https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2017.00018, 2017.

Moody, E. K., Corman, J. R., Elser, J. J., and Sabo, J. L.: Diet composition affects the rate and N:P ratio of fish excretion, Freshwater Biology, 60, 456–465, https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.12500, 2015.

Mraz, J., Mandal, B., Vrba, J., Kajgrova, L., Blaha, M., Kuebutornye, F. K. A., Zabransky, L., Nahlik, V., Lepic, P., and Roy, K.: Nutritional requirement of European fishponds to achieve low and efficient feed use avoiding eutrophication, Aquaculture, 613, 743389, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2025.743389, 2025.

Müller-Navarra, D. C.: Food web paradigms: the biochemical view on trophic interactions, International Review of Hydrobiology, 93, 489–505, https://doi.org/10.1002/iroh.200711046, 2008.

Müller-Navarra, D. C. and Ruess, L.: Editorial: Essential biomolecules caught in the food web?, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 471, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00471, 2019.

Newton, P., Civita, N., Frankel-Goldwater, L., Bartel, K., and Johns, C.: What is regenerative agriculture? A review of scholar and practitioner definitions based on processes and outcomes, Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4, 577723, https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.577723, 2020.

Parent, S. É., Parent, L. E., Egozcue, J. J., Rozane, D. E., Hernandes, A., Lapointe, L., Hébert-Gentile, V., Naess, K., Marchand, S., Lafond, J., Mattos, D., Barlow, P., and Natale, W.: The plant ionome revisited by the nutrient balance concept, Frontiers in Plant Science, 4, 39, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00039, 2013.

Peres, H. and Oliva-Teles, A.: Effect of the dietary essential to non-essential amino acid ratio on growth, feed utilization and nitrogen metabolism of European sea bass (Dicentrarchus labrax), Aquaculture, 256, 395–402, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.02.010, 2006.

Richardson, K., Steffen, W., Lucht, W., Bendtsen, J., Cornell, S. E., Donges, J. F., Drüke, M., Fetzer, I., Bala, G., von Bloh, W., Feulner, G., Fiedler, S., Gerten, D., Gleeson, T., Hofmann, M., Huiskamp, W., Kummu, M., Mohan, C., Nogués-Bravo, D., Petri, S., Porkka, M., Rahmstorf, S., Schaphoff, S., Thonicke, K., Tobian, A., Virkki, V., Wang-Erlandsson, L., Weber, L., and Rockström, J.: Earth beyond six of nine planetary boundaries, Science Advances, 9, eadh2458, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.adh2458, 2023.

Říha, M., Rabaneda-Bueno, R., Prchalová, M., Kajgrová, L., Meador, T. B., Bláha, M., Draštík, V., Kočvara, L., Kuklina, I., and Veselý, L.: Integrating high-resolution telemetry and stable isotope analysis to link behavior, diet, and growth in pond-reared carp, Aquacultural Engineering, 112, 102641, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaeng.2025.102641, 2026.

Rombenso, A. N., Turchini, G. M., and Trushenski, J. T.: The omega-3 sparing effect of saturated fatty acids: A reason to reconsider common knowledge of fish oil replacement, Reviews in Aquaculture, 14, 213–217, https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12593, 2022.

Roy, K., Vrba, J., Kajgrova, L., and Mraz, J.: The concept of balanced fish nutrition in temperate European fishponds to tackle eutrophication, Journal of Cleaner Production, 364, 132584, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132584, 2022.

Roy, K., Másílko, J., Kajgrova, L., Kuebutornye, F. K. A., Oberle, M., and Mraz, J.: End-of-season supplementary feeding in European carp ponds with appropriate plant protein and carbohydrate combinations to ecologically boost productivity: Lupine, rapeseed and, triticale, Aquaculture, 577, 739906, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2023.739906, 2023.

Roy, K., Vrba, J., Kuebutornye, F. K. A., Dvorak, P., Kajgrova, L., and Mraz, J.: Fish stocks as phosphorus sources or sinks: Influenced by nutritional and metabolic variations, not solely by dietary content and stoichiometry, Science of the Total Environment, 938, 173611, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173611, 2024a.

Roy, K., Zabransky, L., Petraskova, E., Machova, Z., Tomcala, A., and Mraz, J.: Dynamics of amino and fatty acids in pond pelagic plankton consortia: Links to temperature, photoperiod and grazing pressure of consumers, AQUA2024, Copenhagen, August 2024, https://eurofish.dk/PDF/Light-abstracts/10.pdf (last access: 9 February 2026), 2024b.

Roy, K., Kajgrova, L., Capkova, L., Zabransky, L., Petraskova, E., Dvorak, P., Nahlik, V., Kuebutornye, F. K. A., Blabolil, P., Blaha, M., Vrba, J., and Mraz, J.: Synergistic digestibility effect by planktonic natural food and habitat renders high digestion efficiency in agastric aquatic consumers, Science of the Total Environment, 927, 172105, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.172105, 2024c.

Roy, K., Verdegem, M. C. J., and Mraz, J.: Ecological restoration of inland aquaculture in land-locked Europe: the role of semi-intensive fishponds and multitrophic technologies in transforming food systems, Reviews in Aquaculture, 17, e12999, https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12999, 2025.

Ruess, L. and Müller-Navarra, D. C.: Essential biomolecules in food webs, Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution, 7, 269, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2019.00269, 2019.

Ruohonen, K., Vielma, J., and Grove, D. J.: Low-protein supplement increases protein retention and reduces the amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus wasted by rainbow trout fed on low-fat herring, Aquaculture Nutrition, 5, 83–91, 1999.

Sarker, P. K., Fournier, J., Boucher, E., Proulx, E., de la Noüe, J., and Vandenberg, G. W.: Effects of low phosphorus ingredient combinations on weight gain, apparent digestibility coefficients, non-fecal phosphorus excretion, phosphorus retention and loading of large rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), Animal Feed Science and Technology, 168, 241–249, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2011.04.086, 2011.

Scheffer, M.: Ecology of shallow lakes, Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-3154-0, 1998.

Scheffer, M. and van Nes, E. H.: Shallow lakes theory revisited: various alternative regimes driven by climate, nutrients, depth and lake size, in: Shallow lakes in a changing world, edited by: Gulati, R. D., Lammens, E., Pauw, N., and Donk, E., Springer, 455–466, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-6399-2_41, 2007.

Šetlíková, I., Bláha, M., Navrátil, J., Policar, T., and Berec, M.: Comparison of periphyton growth on two artificial substrates in temperate zone fishponds, Aquaculture International, 32, 10301–10311, https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-4605597/v1, 2024.

Sharitt, C. A., González, M. J., Williamson, T. J., and Vanni, M. J.: Nutrient excretion by fish supports a variable but significant proportion of lake primary productivity over 15 years, Ecology, 102, e03364, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecy.3364, 2021.

Sommer, U., Adrian, R., De Senerpont Domis, L., Elser, J. J., Gaedke, U., Ibelings, B., Jeppesen, E., Lürling, M., Molinero, J. C., and Mooij, W. M.: Beyond the Plankton Ecology Group (PEG) model: mechanisms driving plankton succession, Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 43, 429–448, 2012.

Sperfeld, E., Wagner, N. D., Halvorson, H. M., Malishev, M., and Raubenheimer, D.: Bridging Ecological Stoichiometry and Nutritional Geometry with homeostasis concepts and integrative models of organism nutrition, Functional Ecology, 31, 286–296, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2435.12707, 2017.

Steffen, W., Richardson, K., Rockström, J., Cornell, S. E., Fetzer, I., Bennett, E. M., Biggs, R., Carpenter, S. R., De Vries, W., and De Wit, C. A.: Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet, Science, 347, 1259855, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1259855, 2015.

Sterner, R. W. and Elser, J. J.: Ecological stoichiometry: the biology of elements from molecules to the biosphere, Princeton University Press, ISSN 0-691-07491-7, 2003.

Sugiura, S. H.: Digestion and absorption of dietary phosphorus in fish, Fishes-Basel, 9, 324, https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes9080324, 2024.

Turchini, G. M., Trushenski, J. T., and Glencross, B. D.: Thoughts for the future of aquaculture nutrition: realigning perspectives to reflect contemporary issues related to judicious use of marine resources in aquafeeds, North American Journal of Aquaculture, 81, 13–39, 2019.

van Dam, A. A., Beveridge, M., Azim, M. E., and Verdegem, M. C.: The potential of fish production based on periphyton, Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries, 12, 1–31, 2002.

Van de Waal, D. and Boersma, M.: Ecological stoichiometry in aquatic ecosystems, Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (EOLSS), edited by: UNESCO-EOLSS Joint Committee, Eolss Publishers, Oxford, UK, https://hdl.handle.net/10013/epic.40842 (last access: 9 February 2026), 2012.

Van de Waal, D. B., Elser, J. J., Martiny, A. C., Sterner, R. W., and Cotner, J. B.: Progress in ecological stoichiometry, Frontiers in Microbiology 9, 1957, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01957, 2018.

Villeger, S., Grenouillet, G., Suc, V., and Brosse, S.: Intra-and interspecific differences in nutrient recycling by European freshwater fish, Freshwater Biology, 57, 2330–2341, 2012.

Watanabe, T., Takeuchi, T., Satoh, S., Wang, K. W., Ida, T., Yaguchi, M., Nakada, M., Amano, T., Yoshijima, S., and Aoe, H.: Development of less-polluting diets for practical fish culture. 3. Development of practical carp diets for reduction of total nitrogen loading on water environment, Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi, 53, 2217–2225, 1987.

Wu, G.: Principles of animal nutrition, CRC Press, ISBN 9781032095998, 2017.

Yamamoto, T., Shima, T., Furuita, H., and Suzuki, N.: Effect of water temperature and short-term fasting on macronutrient self-selection by common carp (Cyprinus carpio), Aquaculture, 220, 655–666, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(02)00541-0, 2003.

You, J. H., Ellis, J. L., Tulpan, D., and Malpass, M. C.: Review: recent advances and future technologies in poultry feed manufacturing, World's Poultry Science Journal, 80, 643–655, https://doi.org/10.1080/00439339.2024.2323536, 2024.