the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Soil nematode communities in extreme environments: adaptations, biogeography, and climate change responses

Tairan Zhang

Wanyanhan Jiang

Background and aims: Extreme environments (polar, alpine, arid) are frontiers of global change, where the interaction between plants and soil biota dictates ecosystem resilience. Soil nematodes are critical components of the soil food web, mediating nutrient cycling. This review synthesizes current understanding of nematode ecology across these systems, focusing on adaptive strategies, biogeographic patterns, and climate change responses. Scope: We combine research from around the world on soil nematodes from polar, alpine, and dry areas. We examine their adaptive strategies, what causes their community structure, and how they respond to climate change. Results: Soil nematode survival is underpinned by convergent adaptations, notably cryptobiosis and opportunistic life histories. While liquid water availability is a universal constraint, biogeographical patterns are shaped by system-specific drivers: temperature thresholds in cold environments and moisture pulses in deserts. Our synthesis reveals that local soil properties and, where present, vegetation patches (e.g., biocrusts, plant rhizospheres) create crucial micro-refugia, often overriding macroclimatic controls. Climate change impacts are primarily indirect; for instance, warming affects nematodes by altering permafrost stability and meltwater regimes in polar regions or by inducing uphill shifts in plant communities in alpine zones, creating mismatches between migrating nematodes and soil development. Conclusions: Soil nematode communities in extreme environments are highly sensitive indicators of climate change, responding to shifts in both abiotic and biotic conditions. Understanding their adaptive limitations and the response pathways is critical for predicting the future of nutrient cycling and the stability of communities in Earth's most vulnerable ecosystems. Future research should focus on the multi-faceted interactions between plants, microbes, and nematodes under combined global change stressors.

- Article

(1040 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Extreme environments are defined as habitats that present severe physiological challenges to the survival, growth, and reproduction of most organisms. In terrestrial ecology, these environments primarily involve three major categories: alpine regions (e.g., alpine zones above the treeline), high-latitude regions (e.g., polar regions), and arid zones (e.g., arid and hyper-arid zones) (Birrell et al., 2020; Wilschut et al., 2019). The characteristics of these environments are the presence of distinct and intense physical or chemical stressors. Specifically, alpine regions are characterized by high ultraviolet radiation, low temperature, and hypoxia (Singh and Singh, 2004); polar regions are characterized by extreme cold, permafrost, and drastic seasonal shifts in photoperiod (Marshall and Turner, 2011); and arid zones are characterized by severe water scarcity and large diurnal temperature fluctuations (Chen et al., 2021; Hu et al., 2017; Li et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2023, 2019).

Due to the inherent ecological fragility and the high sensitivity to environmental change, these extreme environments are considered to be the amplifiers of global climate change (Birrell et al., 2020; Groner et al., 2023). Previous studies revealed that the frequency and intensity of extreme climate events will increase, a development expected to significantly impact ecosystem structure and function, which will more significantly increase in high-latitude and alpine regions (Groner et al., 2023; Morán-Ordóñez et al., 2018; Ruess et al., 1999). For instance, recent research reveals that the Arctic has warmed nearly 4 times faster than the global average over the past 4 decades, with some regions experiencing temperature increases exceeding 0.75 °C per decade (Rantanen et al., 2022). This accelerated warming is driving rapid permafrost thaw and fundamental ecosystem transformation (Liu et al., 2023). Concurrently, the lower biodiversity and simplified food web structures in extreme environments provide an ideal natural laboratory for ecological research (Clitherow et al., 2013; König et al., 2020). Within such systems, the correlations between environmental drivers and biological responses are more discernible, and the effects of climate change on specific communities and key ecological processes are easily distinguished. This reveals fundamental ecological mechanisms that might be obscured in more complex ecosystems (Wall and Virginia, 1999).

Organisms in extreme environments are exposed to environmental stresses such as cold, drought, high salinity, and ultraviolet radiation (Birrell et al., 2020; Osborne et al., 2020; Razgour et al., 2018). Nevertheless, complex organisms remain active in the soil, among which soil nematodes are indispensable key components (Wilschut et al., 2019). As one of the most widely distributed and abundant animals on Earth, nematodes occupy multiple trophic levels even in extreme-environment soil food webs – from feeding on bacteria and fungi to preying on other nematodes (Ferris et al., 2001; Yeates, 2003; Yeates et al., 1993). They play a critical role in biogeochemical cycling, especially the mineralization of carbon and nutrients (van den Hoogen et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019; Pires et al., 2023). Compared with other soil organisms, soil nematodes' taxonomic identification is well established (Yeates et al., 1993), they are extremely sensitive to various changes in soil properties (Bongers and Bongers, 1998; Neher, 2001; Yeates, 2003), and they respond rapidly to short-term environmental shifts (Bongers and Bongers, 1998), making them an ideal model organism for studying how life survives, evolves, and maintains ecosystem functions under extreme environments (Ferris et al., 2001; Yeates, 2003).

In recent years, research focusing on soil nematodes in specific extreme environments has advanced significantly (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023a; Nielsen et al., 2011; Shain et al., 2021; Simmons et al., 2009; Treonis and Wall, 2005; Vlaar et al., 2021). For instance, an 8-year warming and watering experiment in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica, showed that while elevated temperatures reduced the abundance of microbial-feeding nematodes by 42 %, other trophic groups remained unaffected by the warming treatment (Simmons et al., 2009). Meanwhile, studies on the Qingzang Plateau have revealed the critical role of regional-scale environmental factors in structuring nematode communities (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023a). Furthermore, nematodes have even been discovered within the glaciers of the New Zealand Southern Alps, demonstrating their capacity to survive and maintain biodiversity under frozen conditions (Shain et al., 2021).

However, these studies are mainly conducted in isolation, each confined to a single type of extreme environment. Consequently, a systematic review that synthesizes the common principles and unique patterns of nematode communities across these systems (i.e., alpine, polar, and desert) is currently lacking. This review, for the first time, aims to synthesize global research on soil nematodes from alpine, polar, and arid regions, with a primary focus on (1) summarizing and comparing their adaptive strategies in the face of differing environmental stress, (2) dissecting the drivers of their biogeographical patterns to explore potential universal principles, and (3) evaluating their response mechanisms to contemporary climate change and the associated ecological consequences. Through this review, we hope to provide a novel and more comprehensive perspective for understanding the past, present, and future of Earth's most vulnerable underground ecosystems.

To ensure a comprehensive and systematic synthesis, we conducted a literature search using the Web of Science and Scopus databases, covering publications up to October 2024. The search strategy combined keywords related to the target organism (e.g., “soil nematode”), ecosystem types (e.g., “polar”, “Arctic”, “Antarctic”, “alpine”, “arid”, “desert”), and environmental drivers (e.g., “climate change”, “warming”, “precipitation”). We primarily selected peer-reviewed field studies and experimental manipulations that provided mechanistic insights, while excluding purely taxonomic descriptions lacking ecological context.

The adaptation strategies of soil nematodes in extreme environments involves studies of physiological adaptations, life history strategies, and food web structures, among other dimensions. At the core of these strategies lies the goal of maximizing survival and reproductive success under conditions of extremely limited resources and intense environmental stress.

2.1 Physiological adaptations: cryptobiosis and stress tolerance

Nematodes, as one of the most abundant organisms on Earth, can survive in the harshest environments, mainly due to their highly physiological adaptation mechanisms, particularly cryptobiosis (Vlaar et al., 2021). Cryptobiosis is the ability of organisms to enter a state of metabolic stasis under extreme adverse conditions and resume normal life activities once these harsh conditions have passed (Bertolani et al., 2004).

Anhydrobiosis represents a key strategy for nematodes coping with dried environments. By controlling dehydration, nematodes can suspend their metabolic activities to protect cellular structures from damage (Bertolani et al., 2004). This process can involve the loss of over 95 % of their body water and physical contraction to reduce the evaporative surface area (Bertolani et al., 2004), coupled with the synthesis and accumulation of various protective compounds (Liu et al., 2024; Vlaar et al., 2021). Soil nematodes in the McMurdo Dry Valleys of Antarctica, for instance, exhibit this capacity, adopting a coiled morphology, a hallmark of anhydrobiosis, that facilitates their survival under extremely cold, saline, and arid conditions (Treonis and Wall, 2005). Meanwhile, cryobiosis is the corresponding adaptive mechanism against extreme cold. Given that the formation of intracellular ice crystals during freezing is typically lethal, nematodes counteract this threat by synthesizing antifreeze proteins and other ice-inhibiting factors, which inhibit the growth and recrystallization of ice, thereby preserving cellular integrity and function (Kletetschka and Hruba, 2015).

These physiological adaptations profoundly enhance the survival of nematodes in extreme environments. By suspending or drastically reducing their metabolic activity, nematodes can endure unfavorable periods and rapidly resume activity once conditions become favorable. This resilience enables them to colonize and persist in ecosystems such as the arid soils of Antarctica or other seasonally arid regions (Nielsen et al., 2011; Treonis and Wall, 2005). Furthermore, this capacity facilitates their broad geographical dispersal. The simplified community structure of nematodes on Ross Island, Antarctica, for example, is considered to be the result of these adaptations; hence, the responses of this community to climatic shifts in temperature and precipitation are expected to have significant impacts on local population dynamics (Nielsen et al., 2011).

2.2 Life history strategies: simplification and opportunism

The fluctuating and unpredictable resource availability in extreme environments promotes the adoption of opportunists, of which life history are r-strategies among nematode communities (Ferris et al., 2001; Yeates et al., 1993). This strategy prioritizes rapid growth and reproduction to maximize population increases during transiently favorable periods, rather than investing heavily in competitive ability or long-term persistence. The physiological basis for this strategy includes (1) short generation times (often <2 weeks), allowing multiple reproductive cycles within brief favorable windows; (2) high fecundity (>50 eggs per female); and (3) low metabolic maintenance costs, enabling survival during unfavorable periods with minimal energy expenditure (Bongers and Bongers, 1998).

In extreme environments, particularly those characterized by high disturbance frequencies or intermittent resource availability, nematode communities are typically dominated by taxa with low colonizer–persister (cp) values, ranging from 1 to 5, where low values represent r-strategists with short generation times and high tolerance to disturbance, while high values represent K-strategists sensitive to stress (Ferris et al., 2001; Yeates, 2003; Yeates et al., 1993). These nematodes generally possess short generation times, high reproductive ability, and the capacity to respond rapidly to environmental disturbances like drought and soil tillage (Bongiorno et al., 2019; Pedra et al., 2024). For instance, the order Rhabditida was the predominant nematode taxon in both bare soil and soils that had undergone 10 years of cultivation (Pedra et al., 2024). This life history strategy enables them to exploit ephemeral ecological windows, such as rainfall events following a drought or brief warm spells, to rapidly expand their populations (Xiong et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2020a). In the desert steppe of Inner Mongolia, it shows that nematode communities exhibit tolerance to warming, though warming primarily impacts the diversity and stability of deep-soil nematodes, whereas nitrogen deposition predominantly affects shallow-soil communities (Gao et al., 2023).

Extreme environments are generally characterized by low biodiversity (Heatwole and Miller, 2019). For soil nematode communities, it indicates a simplified community composition where a few highly adapted species become dominant (Nielsen et al., 2011). A low cp value of soil nematode community reflects a colonizer-driven structure, with these nematodes primarily functioning as bacterivores and fungivores within the soil food web (Ferris et al., 2001; Yeates et al., 1993). For instance, the terrestrial biota of the Larsemann Hills in Antarctica exhibits low species diversity and limited taxonomic breadth (Heatwole and Miller, 2019). Such simplified systems provide a unique opportunity to investigate adaptive mechanisms and the fundamentals of community structure and dynamics under extreme environmental constraints.

2.3 Food web structure: truncated and specialized

In extreme environments, soil food webs typically exhibit simplified and specialized structures, a characteristic closely linked to resource limitation and low biodiversity (Potapov et al., 2023). Predators (cp-4, cp-5) and omnivores (cp-3, cp-4, cp-5) require a continuous and abundant biomass at lower trophic levels (Ferris et al., 2001; Yeates et al., 1993). In environments characterized by pulsed resource availability and extremely low primary productivity, trophic transfer efficiency is poor, preventing energy from reaching the apex of the food web (Potapov et al., 2023). For instance, the soil food web in the Antarctic Dry Valleys consists of only a few species of microbivorous nematodes and protozoa, with a complete absence of higher-level predators (Nielsen et al., 2011).

To consider the scarcity or absence of vascular plants, the energy flow of soil food webs in extreme environments relies almost exclusively on microorganisms (e.g., bacteria, fungi, algae) capable of chemo- or photosynthesis (Potapov et al., 2023). Hence, nematode communities are dominated by bacterivores and fungivores, forming a highly specialized, microbe-based energy channel (Cesarz et al., 2015). This dependence tightly couples the stability of the entire ecosystem to the dynamics of the microbial community, meaning that any disturbance impacting microorganisms can rapidly cascade through to the nematodes and the food web as a whole (Bongiorno et al., 2019; Sánchez-Moreno and Ferris, 2018).

In summary, soil nematodes exhibit multi-level adaptations to extreme environments, ranging from molecular-level physiological protection mechanisms (cryptobiosis) to population-level rapid reproduction strategies (r-strategy) and further extending to simplified food web structures at the ecosystem level. Collectively, these adaptive traits have shaped the ability of nematodes to survive and evolve in Earth's harshest habitats, establishing them as crucial model organisms for understanding the impacts of climate change on ecosystems (Liu et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2011).

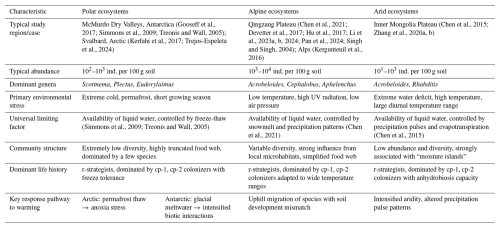

The response pathways of nematode communities to climate change in polar and alpine ecosystems exhibit significant regional divergence and complexity, comprehensively influenced by factors such as water availability, local environmental conditions, and biotic interactions (Table 1) (Ernakovich et al., 2014; Mawarda et al., 2020; Wilschut et al., 2019). Although these cold regions face common challenges in the context of global warming, their responses appear to follow convergent evolutionary trajectories (Gooseff et al., 2017; Mawarda et al., 2020).

Table 1A comparative summary of biogeographical characteristics of soil nematode communities across 203 different extreme environments.

3.1 Polar ecosystems: the Arctic and Antarctic

As one of the regions most sensitive to climate change, the Arctic soils exhibit low average abundance of soil nematodes. A global-scale synthesis reveals that polar and subpolar tundra regions support nematode densities that are 1 to 2 orders of magnitude lower than temperate grasslands (van den Hoogen et al., 2019). This is attributable to the harsh climate, sparse vegetation, and nutrient-poor soils (Song et al., 2017). As an amplifier of global climate change, the impacts of permafrost degradation, active layer deepening, and altered soil temperature and hydrology on the entire soil biota are pervasive in the Arctic (Christiansen et al., 2025; Kerfahi et al., 2017; Romanowicz and Kling, 2022). Specifically, the warming effect is primarily manifested in permafrost thaw, which leads to the physical collapse of landforms. This process triggers widespread soil waterlogging and anoxia, fundamentally altering nematode habitats. Compared to the direct increase in temperature, the anoxic environment caused by this abrupt physical state change (from solid to liquid) is the key factor leading to the decline of nematode communities (Mawarda et al., 2020; Van Daele et al., 2025).

In contrast to the Arctic, climate warming in the hyper-arid ecosystem of the McMurdo Dry Valleys in Antarctica paradoxically acts as a disturbance to the existing community by increasing glacial meltwater (Barrett et al., 2008; Gooseff et al., 2017; Simmons et al., 2009). This increased moisture imposes multiple stressors on the dominant species Scottnema lindsayae, which is highly adapted to arid conditions (Barrett et al., 2008). Specifically, the water dissolves soil salts, causing osmotic shock (Barrett et al., 2008). Concurrently, the added moisture creates favorable conditions for the expansion of hydrophilic competitors (e.g., Plectus spp.) and predators (e.g., Eudorylaimus antarcticus) (Gooseff et al., 2017). These factors collectively lead to a sharp decline in the population of S. lindsayae. Although community evenness increases, there is a net decrease in the total biomass of soil fauna. This change marks a fundamental shift in community assembly rules: from abiotic to biotic control of community assembly (Gooseff et al., 2017).

3.2 High-altitude ecosystems: the alpine zone

Alpine ecosystems share the stress of low temperatures with polar ecosystems but also face unique challenges such as intense ultraviolet radiation, low atmospheric pressure, and more drastic diurnal temperature fluctuations (Li et al., 2023b). In such ecosystems, the biogeographical patterns of soil nematodes present a high degree of complexity and uncertainty, and no universal pattern exists (Chen et al., 2021; Devetter et al., 2017; van den Hoogen et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023a; Pan et al., 2024).

As the “Third Pole”, the Qingzang Plateau provides a unique natural laboratory for studying alpine nematode biogeography. Large-scale research in this region reveals that the distribution patterns of soil nematodes are not simply determined by a single climatic gradient (temperature or precipitation) but are governed by the complex interaction between the two (Chen et al., 2021). For example, in areas with less precipitation, warming enhances soil moisture through snowmelt, benefiting nematodes. Conversely, in wetter areas, warming may intensify evapotranspiration, causing drought stress. This indicates that effective moisture availability, rather than precipitation per se, is the critical determinant. At finer spatial scales, elevational gradients reveal pronounced community zonation: nematode abundance and diversity decline significantly with increasing elevation, with the steepest decline occurring at higher elevations (Chen et al., 2024; Li et al., 2024). This elevational pattern is accompanied by systematic shifts in trophic structure, bacterivorous nematodes (e.g., Acrobeloides, Cephalobus, Plectus) dominate at lower, more productive elevations, whereas the relative proportion of fungivorous and omnivorous nematodes increases at higher elevations where fungal decomposition pathways become more important (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024). However, these broad climatic and elevational trends are frequently overridden by local-scale heterogeneity in soil properties (such as soil organic matter and pH) and often have greater explanatory power for nematode communities than macroclimatic gradients (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023a), vegetation cover, and biotic disturbances such as animal burrowing (Zhang et al., 2025a), which collectively can explain more variance in nematode communities (van den Hoogen et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2019).

Similar patterns, where local microhabitat diversity overrides broad climatic gradients (Kergunteuil et al., 2016; Shain et al., 2021), have been documented in other alpine systems. In the glacier forelands of the New Zealand Southern Alps, nematode community succession is tightly coupled with the process of soil development (Shain et al., 2021). In the European Alps, research has found that high-elevation grasslands host very high nematode diversity, which is related to the diversity of local microhabitats (Kergunteuil et al., 2016). Overall, in alpine regions, the macroclimate sets the broad context for survival, but it is the “microclimate” and local soil conditions that ultimately determine nematode community structure.

3.3 Arid ecosystems: deserts and drylands

Water deficit is the primary characteristic of arid ecosystems. As aquatic organisms, the activity, foraging, and reproduction of soil nematodes all depend on the water films surrounding soil particles; thus, moisture availability directly constrains their survival and distribution (Chen et al., 2021; Yeates, 2003). In arid and hyper-arid regions, the life activities of nematodes are strictly confined to spatiotemporal “moisture islands” (Faist et al., 2021), localized patches where soil moisture is temporarily or persistently higher than the surrounding matrix, such as plant rhizospheres and biological soil crusts. Spatially, these biological “hotspots” include the plant rhizosphere and biological soil crusts (biocrusts). These structures enhance water infiltration, soil stability, and nutrient cycling, creating favorable microhabitats that support higher nematode abundance and diversity (Faist et al., 2021; Zhang and Liu, 2024). Temporally, the life activities of nematodes are synchronized in “pulses” with rare rainfall events. Studies have shown that extreme drought is more destructive to soil microbial communities than gradual climate change, and drought intensity is a decisive factor in shaping the community structure and stability of desert steppe nematodes (Philipp et al., 2025). In extreme deserts, the presence of liquid water can sometimes paradoxically limit the survival of organisms, which in a desiccated state are more resistant to extreme high temperatures and ultraviolet radiation (Cockell et al., 2017).

3.4 Common drivers and divergent patterns

Across all extreme environments, water availability is generally considered a universal primary limiting factor. Whether in polar, alpine, or arid ecosystems, the lack or instability of water directly affects the properties of soil, nutrient transport, microbial activity, and plant growth, which in turn shape the composition and function of nematode communities (Chen et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2019; Philipp et al., 2025; Song et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2020b).

The 0 °C temperature threshold is critical in both polar and alpine systems for distinguishing freezing/thawing and influencing biological activity. The thaw of permafrost and deepening of the active layer are directly related to the increased duration of temperatures above 0 °C (Chen et al., 2021; Mawarda et al., 2020; Van Daele et al., 2025). However, the thermal state of permafrost in different regions can lead to varied response patterns of nematode communities to climate warming. Besides 0 °C, other temperature thresholds also significantly affect nematode physiology: the optimal temperature range for the survival and reproduction of nematodes is typically 20–25 °C, with significant inhibition below 5 °C or above 30 °C (Majdi et al., 2019; Song et al., 2017). Laboratory studies have shown that soil temperature and moisture have complex interactive effects on the abundance, diversity, composition, and carbon footprint of nematode communities. Moisture is the primary driver of community composition, and while the singular effect of temperature is weaker, its interaction with moisture is crucial (Zheng et al., 2023).

The biogeographical patterns of extreme environments are complex and diverse, and their ecological driving mechanisms are often the result of the combined effects of large-scale climatic factors and local microenvironmental conditions. Global-scale studies indicate that latitude, climate, and vegetation type are key drivers of terrestrial nematode distribution and diversity (van den Hoogen et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023a; Liu et al., 2019; Nielsen et al., 2014; Wilschut et al., 2019). At the micro-scale, however, local soil factors (such as pH, bulk density, dissolved organic carbon, and soluble organic nitrogen) can often better explain variations in nematode community structure (Chen et al., 2015, 2021; Nielsen et al., 2014; Zheng et al., 2023).

Global change, particularly accelerated climate warming and altered hydrological patterns, is exerting profound and complex impacts on nematode communities in extreme environments. Recent syntheses indicate that the effects of different global change factors on nematodes vary significantly: drought and nitrogen deposition cause the most drastic changes to community structure, whereas warming has a relatively small direct effect on total abundance but induces deeper impacts by altering species composition and trophic structure (Zhou et al., 2022). This highlights the importance of shifting from single-factor experiments to multi-factor approaches to more accurately predict the future trajectory of subterranean ecosystems.

4.1 Responses to warming

The propagation mechanisms and ecological consequences of climate warming differ among extreme environments, yet they all point toward a fundamental restructuring of community assembly mechanisms. In the Arctic, the primary ecological consequences of warming are permafrost thaw and dramatic shifts in vegetation communities, including shrubification and the expansion of graminoids. For nematodes, these changes are primarily mediated through plant–microbe–nematode cascading effects (Nielsen and Wall, 2013). On one hand, a deeper active layer theoretically expands their habitat space (Sjöberg et al., 2021); on the other hand, the formation of thermokarst topography often leads to poor drainage, soil waterlogging, and anoxia. This abrupt physical state change, from a frozen-aerobic to a thawed-anoxic state, can significantly reduce nematode abundance and diversity, especially for aerobic bacterivores and fungivores (Nitzbon et al., 2024; Pires et al., 2023).

More importantly, warming-induced shifts in microbial community function are reshaping the foundation of the subterranean food web. Recent mechanistic studies indicate that in the high Arctic, fungal communities play a principal role in soil carbon stabilization during early pedogenesis, a process significantly modulated by warming (Trejos-Espeleta et al., 2024). This warming-driven enhancement of fungal dominance shifts the soil microbial composition, which subsequently cascades to affect the nematode community structure. Specifically, the proportion of fungivorous nematodes increases at the expense of bacterivores (Chen et al., 2015; Neher, 2001). Simultaneously, changes in the quality of root exudates and litter from altered vegetation further regulate microbial community composition, thereby indirectly determining the trophic structure of the nematode community (Yergeau et al., 2012). This evidence reveals the core driver of Arctic nematode community change: multi-level indirect effects cascading from vegetation to microbes to nematodes, rather than the direct effect of temperature.

Unlike the Arctic, the Antarctic Dry Valleys have almost no vascular plants; therefore, nematode communities respond primarily and directly to changes in temperature and moisture, as well as to shifts in microbial communities (Nielsen et al., 2011). As previously mentioned, increased meltwater disrupts the hyper-arid equilibrium (Nielsen et al., 2011; Simmons et al., 2009), but its deeper ecological significance points to a paradigm shift in community assembly rules: from a history of species filtering by extreme abiotic stress (e.g., drought) to a future where community dynamics are driven by biotic interactions (e.g., competition, predation) (Gooseff et al., 2017; Simmons et al., 2009). This transition can occur over a short period, much faster than the gradual changes in the Arctic, and may be irreversible, meaning the community is unlikely to return to its original state even if climatic conditions were to recover.

In alpine ecosystems, warming drives vegetation zones to migrate to higher elevations, and soil nematodes are theoretically expected to follow them upslope. However, this process is fraught with spatiotemporal mismatches. Firstly, the rate of change in soil properties is much slower than the response of climate and vegetation, meaning upwardly migrating nematodes may encounter maladapted soil environments (Devetter et al., 2017; Frey et al., 2016; Kergunteuil et al., 2016). Secondly, vast differences in the dispersal ability, adaptability to new environments, and competitive strength against new neighbors among nematode species lead to community reorganization that is stochastic and unpredictable (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023a). A shrub removal experiment on the Qingzang Plateau showed that warming, by altering plant communities and soil properties, indirectly reduced nematode body size and reproductive rates, which could weaken their ability to disperse to higher elevations (Yang et al., 2025).

4.2 Responses to altered hydrological regimes

Water is the primary limiting factor for life in extreme environments. Notably, global change is altering not only the total amount of precipitation but also its spatiotemporal distribution and predictability (Ernakovich et al., 2014). This fundamental alteration of hydrological rhythms will have profound and lasting impacts on nematode communities.

The trend of aridification is intensifying globally, but its impact on nematode communities in extreme environments follows a complex pattern. Extreme drought events selectively filter for bacterivorous nematodes with anhydrobiotic capabilities, while predators and omnivores at a higher trophic level often suffer irreversible population declines. Energy flow is increasingly concentrated in the fundamental pathway of microbivorous nematodes, while consumers at higher trophic levels are gradually disappearing (Chen et al., 2015; Philipp et al., 2025). Furthermore, the recovery of soil properties disrupted by drought, such as the breakdown of soil aggregates, reduced pore connectivity, and loss of microbial diversity, can take years or even decades. The slow recovery of these soil properties directly constrains the rebuilding of the nematode community (Lu et al., 2023).

More subtle, but equally important, are the indirect effects of drought mediated by plant communities. In semi-arid ecosystems, persistent drought promotes the encroachment of drought-tolerant shrubs into grasslands. The litter from these shrubs has a higher ratio and content of secondary metabolites, altering the functional composition of the soil microbial community and, in turn, reshaping the nematode community (Chen et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2020). This two-way process, involving both “bottom-up” and “top-down” controls, ultimately leads to the functional degradation of the soil food web, a degradation that may persist long after the drought has ended (Araujo et al., 2024).

In polar and alpine regions, the hydrological rhythm depends on the seasonal moisture supply provided by spring snowmelt (Ernakovich et al., 2014). Climate warming is causing earlier snowmelt and accelerated glacier melt, while it extends the potential growing season for nematodes, whereas it can trigger “false spring” phenomena, where an early thaw is followed by late frosts, causing freeze damage (Schiestl et al., 2025). More critically, if the spring meltwater is depleted too early and not effectively replenished by summer rains, it can lead to seasonal drought in the mid- to late growing season, strongly inhibiting nematode activity (Sorensen and Michelsen, 2011). This transition from a snowmelt-dominated to a rainfall-dominated hydrological pattern, along with its cascading effects, poses a major challenge to the subterranean world of cold ecosystems.

4.3 Responses to biotic invasions, range shifts, and anthropogenic disturbances

Climate change not only alters the living conditions for native species but also provides an opportunity for the invasion and colonization of non-native species (Jan et al., 2025; Sorte et al., 2013). The harsh climate of extreme environments once served as a natural barrier preventing the invasion of species from lower altitudes and latitudes, but as warming progresses, these barriers are weakening (Shepard et al., 2021). Studies show that some highly adaptable temperate plants are expanding into polar and alpine regions. The novel root exudates and litter they introduce can completely alter local microbial communities, thereby creating cascading effects on nematodes that feed on these microbes (Dutta and Phani, 2023; Wilschut et al., 2019, p. 20). Even more concerning is that warming may facilitate the spread of plant-parasitic nematodes into new regions. Review studies indicate that the geographic distribution of many agricultural pest nematodes is expanding toward higher latitudes and elevations as temperatures rise, establishing stable populations in these new environments (Dutta and Phani, 2023). A global meta-analysis reveals that the impact of climate change on soil animal communities is most significant in polar and arid regions, where the risk of biodiversity loss is highest (van den Hoogen et al., 2019; Li et al., 2023b; Razgour et al., 2018). Once these dominant species decline due to climate change or competition from invasive species, there may be no functional substitutes to fill their ecological niches, as the low species diversity in extreme environments implies low functional redundancy (Treonis and Wall, 2005).

In summary, the impacts of global change on nematode communities in extreme environments are multidimensional, multiscale, and highly non-linear. From alterations in physical conditions to the reorganization of ecosystem functions, from changes in hydrological rhythms to the reshaping of biogeographical patterns, these intertwined processes collectively shape the future trajectory and resilience of Earth's most fragile subterranean ecosystems.

Beyond climate-driven changes and biological invasions, direct anthropogenic disturbances are increasingly affecting nematode communities in extreme environments. In alpine grasslands of the Qingzang Plateau, fungicide application has been shown to reduce nematode diversity by 25 %–40 % and simplify food web structure, with effects stronger than nitrogen enrichment alone (Zhang et al., 2025b). This is particularly concerning because fungicides not only directly kill fungivorous nematodes but also indirectly affect bacterivores by altering the bacteria-to-fungi ratio in soil. In regions where traditional nomadic pastoralism is being replaced by intensive livestock management, such chemical inputs may synergize with climate warming to push nematode communities toward simplified, degraded states. Given the low functional redundancy in extreme environments, these anthropogenic pressures may have disproportionately large and long-lasting impacts on ecosystem functioning.

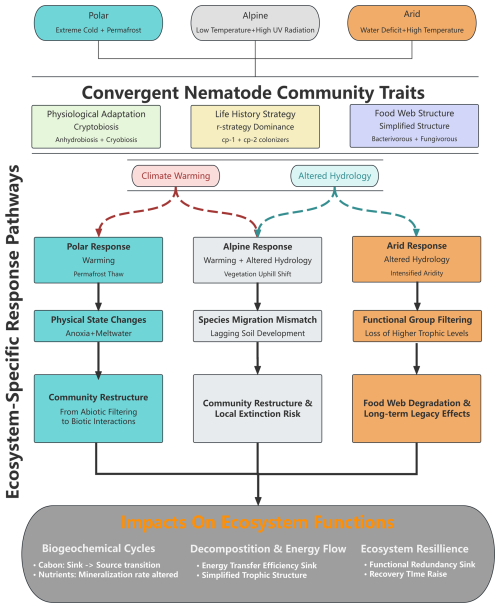

This review, for the first time, systematically integrates research progress on soil nematodes in polar, alpine, and arid regions, revealing the survival strategies, spatial patterns, and response mechanisms to global change of nematode communities in these natural laboratories for studying life under extreme stress. Through a cross-system comparative analysis, we found that although different extreme environments vary significantly in the type and intensity of stressors, nematode communities exhibit several common traits of convergent evolution while also retaining environment-specific adaptive patterns (Fig. 1).

5.1 Key findings

-

Convergent functional strategies across disparate systems. Despite geographic isolation and distinct environmental constraints, nematode communities in polar, alpine, and arid ecosystems have independently evolved similar adaptive traits, including low colonizer–persister (cp) values (1–2), anhydrobiotic capacity, and truncated food webs dominated by bacterivores (typically 60 %–80 % of total abundance). This convergence suggests that extreme environmental filtering imposes predictable selective pressures that transcend regional biogeographic histories.

-

Multi-scalar drivers operating hierarchically. Nematode distribution patterns emerge from hierarchical interactions spanning micro- to macro-scales. At macro-scales (>1 km), climate and biogeography explain 40 %–60 % of community variance; at meso-scales (10 m–1 km), edaphic factors (soil moisture, pH) account for an additional 20 %–35 %; while at micro-scales (<10 m), biotic interactions and stochastic processes dominate. Critically, the relative importance of these drivers shifts predictably along environmental gradients, with abiotic filters prevailing under harsher conditions.

-

Non-linear responses and threshold dynamics. Nematode communities exhibit discontinuous responses to environmental change, characterized by abrupt transitions at critical thresholds (e.g., 0 °C for freeze–thaw cycles, 5 %–10 % soil moisture for anhydrobiosis activation). These thresholds delineate distinct ecological regimes, wherein community assembly mechanisms shift from environmental filtering to stochastic processes. Such non-linearities render simple extrapolations from current trends unreliable for predicting future community states.

5.2 Knowledge gaps

Despite recent advances, fundamental uncertainties persist across multiple dimensions. At the mechanistic level, we lack quantitative frameworks linking physiological tolerance thresholds to population-level responses. For instance, while anhydrobiotic capacity is well documented at the individual level, its translation into demographic resilience remains unclear – particularly regarding the trade-offs between survival and reproductive output under fluctuating moisture regimes. Similarly, the molecular basis of cold tolerance (e.g., cryoprotectant production, membrane fluidity adjustments) has been characterized for only a handful of taxa, precluding generalizations about adaptive potential across phylogenetic lineages.

At the community level, our understanding of biotic interactions in extreme environments is rudimentary. Most studies treat nematodes as isolated responders to abiotic stress, neglecting potential feedbacks with microbial communities, plant roots, and predators. For example, warming-induced shifts in bacteria-to-fungi ratios may indirectly restructure nematode trophic guilds, yet such cascading effects remain poorly quantified. Additionally, the role of priority effects and historical contingency in community assembly, to compare with deterministic environmental sorting, requires disentanglement through experimental manipulations.

Methodologically, inconsistent sampling protocols and taxonomic resolution hinder cross-system synthesis. Published studies employ sampling depths ranging from 0–5 cm to 0–20 cm, introduce systematic biases in abundance estimates (shallow samples may miss deep-dwelling taxa). Furthermore, reliance on morphological identification underestimates cryptic diversity, as evidenced by molecular studies revealing 2 to 3 times more operational taxonomic units (OTUs) than morphospecies in Antarctic soils. Standardized protocols integrating metabarcoding with traditional approaches are urgently needed.

5.3 Prospects

Research priorities for the next decade should emphasize the following: (i) long-term experiments should be implemented, tracking community dynamics through complete environmental cycles (>5 years). In particular, these experiments should adopt nested sampling designs that simultaneously capture macro-climatic trends and micro-habitat buffering effects. This involves differentiating samples between micro-habitats (e.g., under-canopy vs. interspace) and utilizing micro-sensors to monitor soil moisture and temperature at the nematode-relevant scale (<10 cm), thereby resolving the mismatch between macro-climate data and the actual conditions experienced by soil biota. (ii) Integrative approaches should be developed, coupling genomics, physiology, and demography within trait-based frameworks to quantify how micro-scale heterogeneity influences population persistence. (iii) Cross-system syntheses should be conducted via meta-analyses quantifying effect sizes across polar, alpine, and arid environments.

For conservation, nematode-based indices (Maturity Index, Channel Index) show promise as early warning indicators of ecosystem degradation. Shifts in cp-value distributions may presage soil erosion months before visible vegetation loss, offering a monitoring tool for remote regions where intensive sampling is impractical. To increase practical applicability, we recommend integrating standardized nematode monitoring into global research infrastructures, such as the International Long-Term Ecological Research (ILTER) network and the Soil Biodiversity Observation Network (SoilBON). Specifically, adopting nematode functional indices as a standard biological module within these frameworks would allow cross-site comparisons and enhance the detection of cryptic environmental change.

This paper is a review article synthesizing existing literature. No new software, algorithms, custom scripts, or datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study. All information and data discussed in this review are available in the cited references.

HC: conceptualization, investigation, visualization, writing (original draft). TZ: investigation, writing (original draft). WJ: conceptualization, funding acquisition, project administration, supervision, writing (original draft and review and editing). All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This work was supported by the research projects of “Xinglin Scholars” Nursery Talent in 2021 (grant no. MPRC2021013) from Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine. During the preparation of this article, the authors utilized the large language model Gemini (Google) to assist with language polishing and the drafting of ancillary text, including the non-technical summary, the author contribution statement, and the cover letter.

This research has been supported by the research projects of “Xinglin Scholars” Nursery Talent in 2021 (grant no. MPRC2021013) from Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

This paper was edited by Erinne Stirling and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Araujo, A. S. F., De Medeiros, E. V., Da Costa, D. P., Pereira, A. P. D. A., and Mendes, L. W.: From desertification to restoration in the Brazilian semiarid region: Unveiling the potential of land restoration on soil microbial properties, J. Environ. Manage., 351, 119746, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.119746, 2024.

Barrett, J. E., Virginia, R. A., Wall, D. H., and Adams, B. J.: Decline in a dominant invertebrate species contributes to altered carbon cycling in a low-diversity soil ecosystem, Glob. Change Biol., 14, 1734–1744, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2008.01611.x, 2008.

Bertolani, R., Guidetti, R., Jönsson, I. K., Altiero, T., Boschini, D., and Rebecchi, L.: Experiences with dormancy in tardigrades, J. Limnol., 63, 16, https://doi.org/10.4081/jlimnol.2004.s1.16, 2004.

Birrell, J. H., Shah, A. A., Hotaling, S., Giersch, J. J., Williamson, C. E., Jacobsen, D., and Woods, H. A.: Insects in high-elevation streams: Life in extreme environments imperiled by climate change, Glob. Change Biol., 26, 6667–6684, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15356, 2020.

Bongers, T. and Bongers, M.: Functional diversity of nematodes, Appl. Soil Ecol., 10, 239–251, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(98)00123-1, 1998.

Bongiorno, G., Bodenhausen, N., Bünemann, E. K., Brussaard, L., Geisen, S., Mäder, P., Quist, C. W., Walser, J., and De Goede, R. G. M.: Reduced tillage, but not organic matter input, increased nematode diversity and food web stability in European long-term field experiments, Mol. Ecol., 28, 4987–5005, https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.15270, 2019.

Cesarz, S., Peter Reich, B., Scheu, S., Ruess, L., Schaefer, M., and Eisenhauer, N.: Nematode functional guilds, not trophic groups, reflect shifts in soil food webs and processes in response to interacting global change factors, Pedobiologia, 58, 23–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedobi.2015.01.001, 2015.

Chen, D., Cheng, J., Chu, P., Hu, S., Xie, Y., Tuvshintogtokh, I., and Bai, Y.: Regional-scale patterns of soil microbes and nematodes across grasslands on the Mongolian plateau: Relationships with climate, soil, and plants, Ecography, 38, 622–631, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01226, 2015.

Chen, H., Luo, S., Li, G., Jiang, W., Qi, W., Hu, J., Ma, M., and Du, G.: Large-Scale Patterns of Soil Nematodes across Grasslands on the Tibetan Plateau: Relationships with Climate, Soil and Plants, Diversity, 13, 369, https://doi.org/10.3390/d13080369, 2021.

Chen, J., Zhang, Y., Liu, C., and Huang, L.: Distribution pattern of soil nematode communities along an elevational gradient in arid and semi-arid mountains of Northwest China, Front. Plant Sci., 15, 1466079, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2024.1466079, 2024.

Christiansen, C. T., Engel, K., Hall, M., Neufeld, J. D., Walker, V. K., and Grogan, P.: Arctic tundra soil depth, more than seasonality, determines active layer bacterial community variation down to the permafrost transition, Soil Biol. Biochem., 200, 109624, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2024.109624, 2025.

Clitherow, L. R., Carrivick, J. L., and Brown, L. E.: Food Web Structure in a Harsh Glacier-Fed River, PLoS ONE, 8, e60899, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060899, 2013.

Cockell, C. S., Brown, S., Landenmark, H., Samuels, T., Siddall, R., and Wadsworth, J.: Liquid Water Restricts Habitability in Extreme Deserts, Astrobiology, 17, 309–318, https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2016.1580, 2017.

Devetter, M., Háněl, L., Řeháková, K., and Doležal, J.: Diversity and feeding strategies of soil microfauna along elevation gradients in Himalayan cold deserts, PLOS ONE, 12, e0187646, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0187646, 2017.

Dutta, T. K. and Phani, V.: The pervasive impact of global climate change on plant-nematode interaction continuum, Front. Plant Sci., 14, 1143889, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2023.1143889, 2023.

Ernakovich, J. G., Hopping, K. A., Berdanier, A. B., Simpson, R. T., Kachergis, E. J., Steltzer, H., and Wallenstein, M. D.: Predicted responses of arctic and alpine ecosystems to altered seasonality under climate change, Glob. Change Biol., 20, 3256–3269, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12568, 2014.

Faist, A. M., Antoninka, A. J., Barger, N. N., Bowker, M. A., Chaudhary, V. B., Havrilla, C. A., Huber-Sannwald, E., Reed, S. C., and Weber, B.: Broader Impacts for Ecologists: Biological Soil Crust as a Model System for Education, Front. Microbiol., 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2020.577922, 2021.

Ferris, H., Bongers, T., and De Goede, R. G. M.: A framework for soil food web diagnostics: extension of the nematode faunal analysis concept, Appl. Soil Ecol., 18, 13–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(01)00152-4, 2001.

Frey, B., Rime, T., Phillips, M., Stierli, B., Hajdas, I., Widmer, F., and Hartmann, M.: Microbial diversity in European alpine permafrost and active layers, FEMS Microbiol. Ecol., 92, fiw018, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsec/fiw018, 2016.

Gao, Z., Huang, J., Gao, W., Jia, M., Li, X., Han, G., and Zhang, G.: Exploring the effects of warming and nitrogen deposition on desert steppe based on soil nematodes, Land Degrad. Dev., 34, 682–697, https://doi.org/10.1002/ldr.4486, 2023.

Gooseff, M. N., Barrett, J. E., Adams, B. J., Doran, P. T., Fountain, A. G., Lyons, W. B., McKnight, D. M., Priscu, J. C., Sokol, E. R., Takacs-Vesbach, C., Vandegehuchte, M. L., Virginia, R. A., and Wall, D. H.: Decadal ecosystem response to an anomalous melt season in a polar desert in Antarctica, Nat. Ecol. Evol., 1, 1334–1338, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0253-0, 2017.

Groner, E., Babad, A., Berda Swiderski, N., and Shachak, M.: Toward an extreme world: The hyper-arid ecosystem as a natural model, Ecosphere, 14, e4586, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.4586, 2023.

Heatwole, H. and Miller, W. R.: Structure of micrometazoan assemblages in the Larsemann Hills, Antarctica, Polar Biol., 42, 1837–1848, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-019-02557-6, 2019.

Hu, J., Chen, G., Hassan, W. M., Chen, H., Li, J., and Du, G.: Fertilization influences the nematode community through changing the plant community in the Tibetan Plateau, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 78, 7–16, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2016.11.001, 2017.

Jan, A., Arismendi, I., and Giannico, G.: Double Trouble for Native Species Under Climate Change: Habitat Loss and Increased Environmental Overlap With Non-Native Species, Glob. Change Biol., 31, e70040, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.70040, 2025.

Kerfahi, D., Park, J., Tripathi, B. M., Singh, D., Porazinska, D. L., Moroenyane, I., and Adams, J. M.: Molecular methods reveal controls on nematode community structure and unexpectedly high nematode diversity, in Svalbard high Arctic tundra, Polar Biol., 40, 765–776, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-016-1999-6, 2017.

Kergunteuil, A., Campos-Herrera, R., Sánchez-Moreno, S., Vittoz, P., and Rasmann, S.: The Abundance, Diversity, and Metabolic Footprint of Soil Nematodes Is Highest in High Elevation Alpine Grasslands, Front. Ecol. Evol., 4, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2016.00084, 2016.

Kletetschka, G. and Hruba, J.: Dissolved Gases and Ice Fracturing During the Freezing of a Multicellular Organism: Lessons from Tardigrades, BioResearch Open Access, 4, 209–217, https://doi.org/10.1089/biores.2015.0008, 2015.

König, S., Vogel, H.-J., Harms, H., and Worrich, A.: Physical, Chemical and Biological Effects on Soil Bacterial Dynamics in Microscale Models, Front. Ecol. Evol., 8, 53, https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2020.00053, 2020.

Li, G., Wilschut, R., Luo, S., Chen, H., Wang, X., Du, G., and Geisen, S.: Nematode biomass changes along an elevational gradient are trophic group dependent but independent of body size, Glob. Change Biol., 29, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.16814, 2023a.

Li, X., Liu, Z., Zhang, C., Zheng, L., and Li, H.: Altitudinal variation in soil nematode communities in an alpine mountain region of the eastern Tibetan plateau, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 121, 103617, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2024.103617, 2024.

Li, Z., Yang, Y., Zheng, H., Hu, B., Dai, X., Meng, N., Zhu, J., and Yan, D.: Environmental changes drive soil microbial community assembly across arid alpine grasslands on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, China, Catena, 228, 107175, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2023.107175, 2023b.

Liu, L., Xie, R., Ma, D., Fu, L., and Wu, X.: Effects of snow removal on seasonal dynamics of soil bacterial community and enzyme activity, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 119, 103564, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2023.103564, 2023.

Liu, T., Hu, F., and Li, H.: Spatial ecology of soil nematodes: Perspectives from global to micro scales, Soil Biol. Biochem., 137, 107565, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.107565, 2019.

Liu, Y., Wu, K.-X., Abozeid, A., Guo, X.-R., Mu, L.-Q., Liu, J., and Tang, Z.-H.: Transcriptomic and metabolomic insights into drought response strategies of two Astragalus species, Ind. Crops Prod., 214, 118509, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.118509, 2024.

Lu, L., Li, G., He, N., Li, H., Liu, T., Li, X., Whalen, J. K., Geisen, S., and Liu, M.: Drought shifts soil nematodes to smaller size across biological scales, Soil Biol. Biochem., 184, 109099, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2023.109099, 2023.

Majdi, N., Traunspurger, W., Fueser, H., Gansfort, B., Laffaille, P., and Maire, A.: Effects of a broad range of experimental temperatures on the population growth and body-size of five species of free-living nematodes, J. Therm. Biol., 80, 21–36, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2018.12.010, 2019.

Marshall, G. J. and Turner, J. (Eds.): 1 – Introduction, in: Climate Change in the Polar Regions, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, v–viii, ISBN 9780521850100 2011.

Mawarda, P. C., Le Roux, X., van Elsas, J. D., and Salles, J. F.: Deliberate introduction of invisible invaders: A critical appraisal of the impact of microbial inoculants on soil microbial communities, Soil Biol. Biochem., 148, 107874, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2020.107874, 2020.

Morán-Ordóñez, A., Briscoe, N. J., and Wintle, B. A.: Modelling species responses to extreme weather provides new insights into constraints on range and likely climate change impacts for Australian mammals, Ecography, 41, 308–320, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02850, 2018.

Neher, D. A.: Role of nematodes in soil health and their use as indicators, J. Nematol., 33, 161–168, 2001.

Nielsen, U. N. and Wall, D. H.: The future of soil invertebrate communities in polar regions: different climate change responses in the Arctic and Antarctic?, Ecol. Lett., 16, 409–419, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12058, 2013.

Nielsen, U. N., Wall, D. H., Adams, B. J., and Virginia, R. A.: Antarctic nematode communities: observed and predicted responses to climate change, Polar Biol., 34, 1701–1711, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-011-1021-2, 2011.

Nielsen, U. N., Ayres, E., Wall, D. H., Li, G., Bardgett, R. D., Wu, T., and Garey, J. R.: Global-scale patterns of assemblage structure of soil nematodes in relation to climate and ecosystem properties, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 23, 968–978, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12177, 2014.

Nitzbon, J., Schneider Von Deimling, T., Aliyeva, M., Chadburn, S. E., Grosse, G., Laboor, S., Lee, H., Lohmann, G., Steinert, N. J., Stuenzi, S. M., Werner, M., Westermann, S., and Langer, M.: No respite from permafrost-thaw impacts in the absence of a global tipping point, Nat. Clim. Change, 14, 573–585, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-024-02011-4, 2024.

Osborne, P., Hall, L. J., Kronfeld-Schor, N., Thybert, D., and Haerty, W.: A rather dry subject; investigating the study of arid-associated microbial communities, Environ. Microbiome, 15, 20, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40793-020-00367-6, 2020.

Pan, J., Zhang, X., Liu, S., Liu, N., Liu, M., Chen, C., Zhang, X., Niu, S., and Wang, J.: Precipitation alleviates microbial C limitation but aggravates N and P limitations along a 3000 km transect on the Tibetan Plateau, Catena, 247, 108535, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2024.108535, 2024.

Pedra, F., Inácio, M. L., Fareleira, P., Oliveira, P., Pereira, P., and Carranca, C.: Long-Term Effects of Plastic Mulch in a Sandy Loam Soil Used to Cultivate Blueberry in Southern Portugal, Pollutants, 4, 16–25, https://doi.org/10.3390/pollutants4010002, 2024.

Philipp, L., Blagodatskaya, E., Tarkka, M., and Reitz, T.: Soil microbial communities are more disrupted by extreme drought than by gradual climate shifts under different land-use intensities, Front. Microbiol., 16, 1649443, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2025.1649443, 2025.

Pires, D., Orlando, V., Collett, R. L., Moreira, D., Costa, S. R., and Inácio, M. L.: Linking Nematode Communities and Soil Health under Climate Change, Sustainability, 15, 11747, https://doi.org/10.3390/su151511747, 2023.

Potapov, A., Lindo, Z., Buchkowski, R., and Geisen, S.: Multiple dimensions of soil food-web research: History and prospects, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 117, 103494, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2023.103494, 2023.

Rantanen, M., Karpechko, A. Yu., Lipponen, A., Nordling, K., Hyvärinen, O., Ruosteenoja, K., Vihma, T., and Laaksonen, A.: The Arctic has warmed nearly four times faster than the globe since 1979, Commun. Earth Environ., 3, 168, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00498-3, 2022.

Razgour, O., Persey, M., Shamir, U., and Korine, C.: The role of climate, water and biotic interactions in shaping biodiversity patterns in arid environments across spatial scales, Divers. Distrib., 24, 1440–1452, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12773, 2018.

Romanowicz, K. J. and Kling, G. W.: Summer thaw duration is a strong predictor of the soil microbiome and its response to permafrost thaw in arctic tundra, Environ. Microbiol., 24, 6220–6237, https://doi.org/10.1111/1462-2920.16218, 2022.

Ruess, L., Michelsen, A., Schmidt, I. K., and Jonasson, S.: Simulated climate change affecting microorganisms, nematode density and biodiversity in subarctic soils, Plant Soil, 212, 63–73, https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1004567816355, 1999.

Sánchez-Moreno, S. and Ferris, H.: Nematode ecology and soil health, in: Plant parasitic nematodes in subtropical and tropical agriculture, 62–86, https://doi.org/10.1079/9781786391247.0062, 2018.

Schiestl, F. P., Wartmann, B. A., Bänziger, R., Györög-Kobi, B., Hess, K., Luder, J., Merz, E., Peter, B., Reutlinger, M., Richter, T., Senn, H., Ulrich, T., Waldeck, B., Wartmann, C., Wüest, R., Wüest, W., and Rusman, Q.: The Late Orchid Catches the Bee: Frost Damage and Pollination Success in the Face of Global Warming in a European Terrestrial Orchid, Ecol. Evol., 15, e70729, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.70729, 2025.

Shain, D. H., Novis, P. M., Cridge, A. G., Zawierucha, K., Geneva, A. J., and Dearden, P. K.: Five animal phyla in glacier ice reveal unprecedented biodiversity in New Zealand's Southern Alps, Sci. Rep., 11, 3898, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83256-3, 2021.

Shepard, I. D., Wissinger, S. A., and Greig, H. S.: Elevation alters outcome of competition between resident and range-shifting species, Glob. Change Biol., 27, 270–281, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15401, 2021.

Simmons, B. L., Wall, D. H., Adams, B. J., Ayres, E., Barrett, J. E., and Virginia, R. A.: Long-term experimental warming reduces soil nematode populations in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, Antarctica, Soil Biol. Biochem., 41, 2052–2060, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2009.07.009, 2009.

Singh, S. and Singh, R.: High-altitude clear-sky direct solar ultraviolet irradiance at Leh and Hanle in the western Himalayas: Observations and model calculations, J. Geophys. Res. Atmospheres, 109, https://doi.org/10.1029/2004JD004854, 2004.

Sjöberg, Y., Jan, A., Painter, S. L., Coon, E. T., Carey, M. P., O'Donnell, J. A., and Koch, J. C.: Permafrost Promotes Shallow Groundwater Flow and Warmer Headwater Streams, Water Resour. Res., 57, e2020WR027463, https://doi.org/10.1029/2020WR027463, 2021.

Song, D., Pan, K., Tariq, A., Sun, F., Li, Z., Sun, X., Zhang, L., Olusanya, O. A., and Wu, X.: Large-scale patterns of distribution and diversity of terrestrial nematodes, Appl. Soil Ecol., 114, 161–169, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2017.02.013, 2017.

Sorensen, P. L. and Michelsen, A.: Long-term warming and litter addition affects nitrogen fixation in a subarctic heath, Glob. Change Biol., 17, 528–537, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02234.x, 2011.

Sorte, C. J. B., Ibáñez, I., Blumenthal, D. M., Molinari, N. A., Miller, L. P., Grosholz, E. D., Diez, J. M., D'Antonio, C. M., Olden, J. D., Jones, S. J., and Dukes, J. S.: Poised to prosper? A cross-system comparison of climate change effects on native and non-native species performance, Ecol. Lett., 16, 261–270, https://doi.org/10.1111/ele.12017, 2013.

Trejos-Espeleta, J. C., Marin-Jaramillo, J. P., Schmidt, S. K., Sommers, P., Bradley, J. A., and Orsi, W. D.: Principal role of fungi in soil carbon stabilization during early pedogenesis in the high Arctic, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 121, e2402689121, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2402689121, 2024.

Treonis, A. M. and Wall, D. H.: Soil nematodes and desiccation survival in the extreme arid environment of the Antarctic Dry Valleys, Integr. Comp. Biol., 45, 741–750, https://doi.org/10.1093/icb/45.5.741, 2005.

Van Daele, R., Lee, H., Althuizen, I., and Vandegehuchte, M. L.: Experimental warming and permafrost thaw decrease soil nematode abundance in northern palsa peatlands, Web Ecol., 25, 121–135, https://doi.org/10.5194/we-25-121-2025, 2025.

van den Hoogen, J., Geisen, S., Routh, D., Ferris, H., Traunspurger, W., Wardle, D. A., de Goede, R. G. M., Adams, B. J., Ahmad, W., Andriuzzi, W. S., Bardgett, R. D., Bonkowski, M., Campos-Herrera, R., Cares, J. E., Caruso, T., de Brito Caixeta, L., Chen, X., Costa, S. R., Creamer, R., Mauro da Cunha Castro, J., Dam, M., Djigal, D., Escuer, M., Griffiths, B. S., Gutiérrez, C., Hohberg, K., Kalinkina, D., Kardol, P., Kergunteuil, A., Korthals, G., Krashevska, V., Kudrin, A. A., Li, Q., Liang, W., Magilton, M., Marais, M., Martín, J. A. R., Matveeva, E., Mayad, E. H., Mulder, C., Mullin, P., Neilson, R., Nguyen, T. A. D., Nielsen, U. N., Okada, H., Rius, J. E. P., Pan, K., Peneva, V., Pellissier, L., Carlos Pereira da Silva, J., Pitteloud, C., Powers, T. O., Powers, K., Quist, C. W., Rasmann, S., Moreno, S. S., Scheu, S., Setälä, H., Sushchuk, A., Tiunov, A. V., Trap, J., van der Putten, W., Vestergård, M., Villenave, C., Waeyenberge, L., Wall, D. H., Wilschut, R., Wright, D. G., Yang, J., and Crowther, T. W.: Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale, Nature, 572, 194–198, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1418-6, 2019.

Vlaar, L. E., Bertran, A., Rahimi, M., Dong, L., Kammenga, J. E., Helder, J., Goverse, A., and Bouwmeester, H. J.: On the role of dauer in the adaptation of nematodes to a parasitic lifestyle, Parasit. Vectors, 14, 554, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-021-04953-6, 2021.

Wall, D. H. and Virginia, R. A.: Controls on soil biodiversity: insights from extreme environments, Appl. Soil Ecol., 13, 137–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0929-1393(99)00029-3, 1999.

Wilschut, R. A., Geisen, S., Martens, H., Kostenko, O., De Hollander, M., Ten Hooven, F. C., Weser, C., Snoek, L. B., Bloem, J., Caković, D., Čelik, T., Koorem, K., Krigas, N., Manrubia, M., Ramirez, K. S., Tsiafouli, M. A., Vreš, B., and Van Der Putten, W. H.: Latitudinal variation in soil nematode communities under climate warming-related range-expanding and native plants, Glob. Change Biol., 25, 2714–2726, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14657, 2019.

Xiong, D., Wei, C., Wubs, E. R. J., Veen, G. F., Liang, W., Wang, X., Li, Q., Van der Putten, W. H., and Han, X.: Nonlinear responses of soil nematode community composition to increasing aridity, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 29, 117–126, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13013, 2020.

Yang, Z., Chen, J., Wang, J., Liu, Z., Meng, L., Cui, H., Xiao, S., Zhang, A., Liu, K., An, L., Chen, S., and Nielsen, U. N.: Shrub removal suppresses the effects of warming on nematode communities in an alpine grassy ecosystem, Appl. Soil Ecol., 211, 106117, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.106117, 2025.

Yeates, G. W.: Modelling species responses to extreme weather provides new insights into constraints on range and likely climate change impacts for Australian mammals, Biol. Fertil. Soils, 37, 199–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-003-0586-5, 2003.

Yeates, G. W., Bongers, T., De Goede, R. G. M., Freckman, D. W., and Georgieva, S. S.: Feeding habits in soil nematode families and genera-an outline for soil ecologists., J. Nematol., 25, 315–331, https://doi.org/10.1006/jipa.1993.1100, 1993.

Yergeau, E., Bokhorst, S., Kang, S., Zhou, J., Greer, C. W., Aerts, R., and Kowalchuk, G. A.: Shifts in soil microorganisms in response to warming are consistent across a range of Antarctic environments, ISME J., 6, 692–702, https://doi.org/10.1038/ismej.2011.124, 2012.

Zhang, G., Sui, X., Li, Y., Jia, M., Wang, Z., Han, G., and Wang, L.: The response of soil nematode fauna to climate drying and warming in Stipa breviflora desert steppe in Inner Mongolia, China, J. Soils Sediments, 20, 2166–2180, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11368-019-02555-5, 2020a.

Zhang, Q., Buyantuev, A., Fang, X., Han, P., Li, A., Li, F. Y., Liang, C., Liu, Q., Ma, Q., Niu, J., Shang, C., Yan, Y., and Zhang, J.: Ecology and sustainability of the Inner Mongolian Grassland: Looking back and moving forward, Landsc. Ecol., 35, 2413–2432, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10980-020-01083-9, 2020b.

Zhang, X., Nian, L., Li, L., Liu, X., and Wang, Q.: Soil Nematodes Regulate Ecosystem Multifunctionality Under Different Zokor Mounds in Qinghai–Tibet Alpine Grasslands, Biology, 14, 1200, https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14091200, 2025a.

Zhang, Y. and Liu, B.: Biological soil crusts and their potential applications in the sand land over Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, Res. Cold Arid Reg., 16, 20–29, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcar.2024.03.001, 2024.

Zhang, Y., Xi, H., Whalen, J. K., Han, J., Liu, X., and Liu, Y.: Fungicide, not nitrogen, reduces soil nematode diversity and multifunctionality in alpine grasslands, Appl. Soil Ecol., 215, 106481, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsoil.2025.106481, 2025b.

Zheng, L., Wu, S., Lu, L., Li, T., Liu, Z., Li, X., and Li, H.: Unraveling the interaction effects of soil temperature and moisture on soil nematode community: A laboratory study, Eur. J. Soil Biol., 118, 103537, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejsobi.2023.103537, 2023.

Zhou, J., Wu, J., Huang, J., Sheng, X., Dou, X., and Lu, M.: A synthesis of soil nematode responses to global change factors, Soil Biol. Biochem., 165, 108538, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2021.108538, 2022.

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Nematode adaptation strategies in extreme environments

- Biogeography across poles and peaks

- Responses to global change: impacts on belowground ecosystems

- Conclusions and prospects

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Nematode adaptation strategies in extreme environments

- Biogeography across poles and peaks

- Responses to global change: impacts on belowground ecosystems

- Conclusions and prospects

- Code and data availability

- Author contributions

- Competing interests

- Disclaimer

- Acknowledgements

- Financial support

- Review statement

- References