the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

First documentation of putative mating behavior in blue sharks (Prionace glauca) reveals a potential reproductive area in the Northeast Atlantic

Lennart Vossgaetter

Lukas Müller

Isaias Cruz

Marika Schultz

Anna T. Renner

Maite Erauskin-Extramiana

Reproductive behavior in sharks remains poorly understood, with direct observations of mating reported in only a few species. The blue shark (Prionace glauca) is a widely distributed, placental viviparous species, yet direct evidence of mating behavior remains undocumented. Here, we describe the first visual documentation of a putative mating attempt involving blue sharks in the Bay of Biscay, off the Basque coast, observed during a shark ecotourism dive in July 2023. An adult male and an immature female exhibited a sequence of behaviors consistent with shark courtship, including parallel swimming, following, a courtship bite, and an inversion of both individuals. Additionally, we documented females with mating scars across 4 consecutive years, the majority of which were considered immature. These observations align with prior reports suggesting mating attempts between adult males and immature females. The combination of direct behavioral observation and repeated evidence of mating scars highlights the potential reproductive significance of the region and underscores the need for further research on the demographics, habitat use, and reproductive ecology of blue sharks in the Northeast Atlantic.

- Article

(2170 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(19310 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Reproductive biology and behavior are among the least understood aspects of shark biology, with direct observations of mating documented in only a few species (e.g., Pratt and Carrier, 2011; McCauley et al., 2010; Salinas-de-León et al., 2017). The blue shark (Prionace glauca, Linnaeus, 1758) is a large-bodied placental viviparous species with a circumglobal distribution in temperate and tropical waters (Compagno, 1984). They reach maturity at approximately 190 cm fork length (FL) for both males and females, at around 4–5 years of age (Pratt, 1979; Skomal and Natanson, 2003; Viducic et al., 2022). Typically, blue shark populations are segregated by sex, except for areas where reproductive activity has been documented (e.g., Vandeperre et al., 2014; Calich and Campana, 2015). One of these areas is the continental shelf off the eastern coast of North America, ranging from North Carolina to Newfoundland. In this region, sharks of both sexes and females with mating scars were observed from May until November (Pratt, 1979; Kohler et al., 2002). Notably, instances of mating attempts with immature females have been reported based on mating scars off Nova Scotia, Canada (Calich and Campana, 2015). Despite the species' wide distribution and ecological significance, direct observations of mating behavior in blue sharks have yet to be documented (Calich and Campana, 2015). The understanding of the latter is therefore primarily based on indirect evidence (e.g., mating scars) and analogies drawn from other large shark species (Tricas and Le Feuvre, 1985; Calich and Campana, 2015).

In elasmobranchs, mating generally begins with males and females swimming closely together, sometimes engaging in parallel swimming or circling behaviors. This proximity allows the male to gauge the female's receptivity and readiness to mate (Pratt and Carrier, 2001; Talwar et al., 2023). As part of their courtship behavior, males bite the females, usually on the pectoral fins, flanks, or gill area. The biting helps the male to hold onto the female during copulation, often described as a violent and vigorous process (Carrier et al. 2004). The resulting scars resemble semi-circular jaw impressions and individual tooth cuts and are henceforth termed as mating scars (Stevens, 1974). Such scars are absent in males, indicating a lack of reciprocal biting by females (Pratt, 1979; Tricas and Le Feuvre, 1985). The actual act of copulation involves the male inserting usually one of his claspers into the female's cloaca to transfer sperm. This process can last from a few seconds to several minutes depending on the species (Klimley et al., 2023). Post-copulatory behavior often involves the separation of male and female. The female might exhibit avoidance behavior to escape further advances from the male, which may involve rapid swimming or evasive maneuvers (Gordon, 1993; Pratt and Carrier, 2001). The male may continue to show interest and follow the female for a short period before losing interest or finding another mate (Carrier et al., 2004; Afonso et al., 2016).

In the Bay of Biscay, Europe, blue sharks of both sexes have been recorded in commercial fishing data, including information on presence, sex, and size, whereas observations from fishery-independent sources, such as tagging programs or ecotourism observations, remain scarce (Druon et al., 2022). Blue shark sightings along the continental slope off the Basque Country, northern Spain, were documented through shark ecotourism activities between 2020 and 2022, showing the presence of both males and females with an average size of 1.2 m total length (TL; Cruz et al., unpublished data). However, detailed knowledge of their demographics, reproductive behavior, and patterns of habitat use in this region remains limited. In this brief communication, we use opportunistic data from ecotourism initiatives and research trips to describe (a) the first visual documentation of putative mating behavior of blue sharks and (b) the interannual occurrence of mating scars in females along a submarine canyon system off the Basque coast in the southern Bay of Biscay.

Observations were conducted at two study sites in the southern Bay of Biscay: a submarine canyon area located 7–18 km off Bermeo, Basque Country, Spain, and the Gouf de Capbreton canyon, roughly 18–27 km off Hondarribia, Basque Country, Spain. Both areas include the regions primarily along the continental slope and adjacent shelf at depths of approximately 150–1000 m. Since 2020, the shark ecotourism operator MakoPako has conducted tourism trips off Bermeo typically between June and September. During these activities, sharks were attracted to a drifting boat using albacore tuna (Thunnus alalunga), sardines (Sardina pilchardus), and mackerel (Scomber scombrus). On every trip, photographs of sharks on professional Digital Single Lens Mirrorless (DSLM) cameras (Sony, Panasonic) were collected and saved. The shark's sex was determined based on the presence of claspers, and their length was estimated based on objects of known length (e.g., Rohner et al., 2015). Since 2023, a shark tagging program has used the same methods to attract sharks for tagging purposes off Bermeo and Hondarribia. During tagging activities, length was obtained from direct measurements with a measuring tape, and any obvious markings and injuries were photographed and noted.

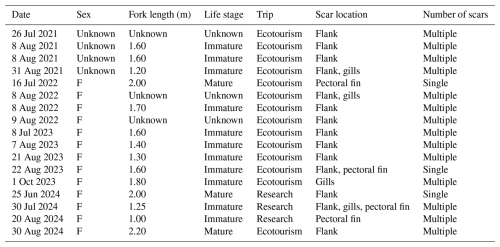

For this analysis, we coalesced all information indicating mating behavior or mating scars on sharks from both ecotourism and research trips. Animals were only included in this study if at least one semi-circular jaw impression was visible. Mating scars were categorized based on their locations on flanks, gills, and/or pectoral fins, and the presence of a single mating scar or multiple mating scars was noted. Individuals were classified as either mature or immature based on published size-at-maturity estimates for blue sharks in the North Atlantic (Viducic et al., 2022; Carlson et al., 2023). Females exceeding 1.90 m FL and males over 1.96 cm FL were considered mature (Carlson et al., 2023).

In addition, one opportunistic observation of putative mating behavior was documented in exceptional detail on 31 July 2023. During this event, sharks were photographed with a Panasonic Lumix GH5 Mark 2 in serial photo mode (up to 12 frames per second) and simultaneously recorded with a Panasonic Lumix S1H in video mode from a different perspective (Supplement).

Between 2021 and 2024, approximately 200 ecotourism trips were conducted off Bermeo, distributed relatively evenly across the 4 years. In addition, 24 dedicated research trips were carried out in 2023 and 2024, including 14 off Hondarribia and 10 off Bermeo (10 in 2023 and 14 in 2024). Across these combined efforts, we collected a total of 17 instances of bite marks on females and noted one observation of putative mating behavior. Of these, 14 cases of mating scars were recorded during ecotourism trips off Bermeo, while three were observed during research activities off Hondarribia.

3.1 Observation of putative mating behavior

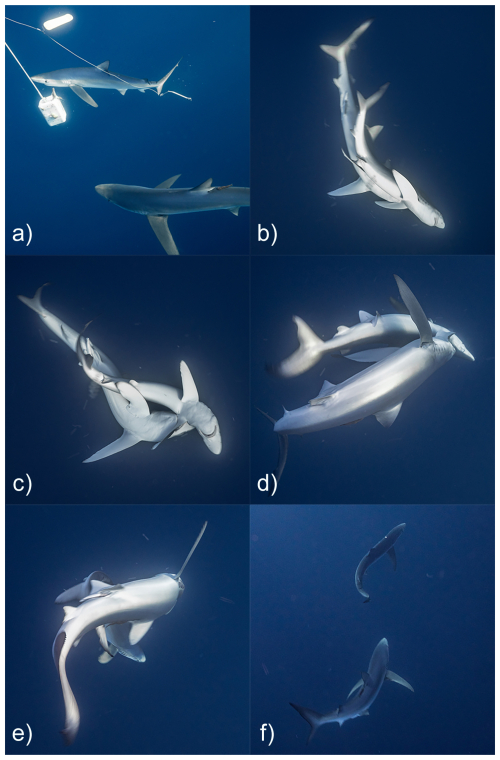

On 31 July 2023, two blue sharks were observed in the Bermeo canyon at 400–600 m depth (8 km offshore). A male erratically followed a female and delivered a courtship bite. The total duration of the interaction was 4 min and 15 s. The detailed sequence of courtship behaviors is described below.

At 18:33:00 LT (local time, UTC+02:00), a male blue shark estimated at 2.2 m FL appeared at the dive site. His claspers were large and appeared rigid (Fig. 1), suggesting it was an adult male. The male made a short pass along the dive site and disappeared out of the visual field of the researchers. 1 min later, a female of roughly 1.8 m FL appeared at the dive site. She was likely an immature female (8 % mature at 180 cm FL; Carlson et al., 2023). She remained alone at the dive site for 2 min before the male appeared again at 18:36:00 LT. At 18:36:56 LT, the male calmly approached the female for the first time, and both sharks swam in parallel to each other towards the bait container, the male slightly behind. This exact behavior was repeated 2 min later, and, at 18:38:52 LT, the female shark reached the bait container before the male. The male continued to follow the female slowly (Fig. 1a). Suddenly, the male began chasing the female at high speeds while trying to bite and grasp her. He succeeded in biting her left pectoral fin at 18:39:42 LT (Fig. 1b). The male subsequently maneuvered the female into an inverted position with her ventral side oriented upward while she continued to move. Both sharks were upside down while the male maintained his grip on the female's left pectoral fin at 18:39:44 LT (Fig. 1c and d). 1 s later, at 18:39:45 LT, the female erratically accelerated to free herself from the bite (Fig. 1d and e). The male pursued her at high speeds for another 30 s until 18:40:15 LT (Fig. 1f, Supplement). The female left the dive site and did not return, whereas the male remained in the area for approximately 1 additional hour until 19:45:46 LT.

Figure 1The observation photographed in serial photo mode, with the male following the female (a) and biting her left pectoral fin (b) and with both sharks inverted (c). The female tries freeing herself from the bite (d) and erratically accelerating away from the male (e). The male starts following the female again (f).

3.2 Mating scars

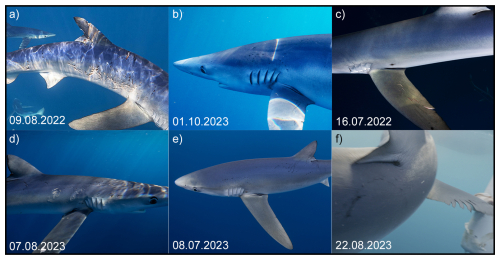

A total of 17 sharks ranging from 1.0 to 2.2 m FL (mean ± SD = 1.6±0.3 m) were documented with mating scars over 4 consecutive years (2021–2024; Table 1). These observations occurred throughout the sampling season, from late June to early October, with the majority recorded in August (64.7 %, N=11). Most sharks were likely immature females (78.6 %, N=11), and the majority had multiple bite marks (82.4 %, N=14). The injuries were primarily located on the flank of the body (82.4 %, N=14) and on the pectoral fin (17.6 %, N=4) and the gill area (17.6 %, N=4; see Fig. 2).

The male clearly exhibited precopulatory behaviors commonly described for other shark species. Such behaviors included following (Johnson and Nelson, 1978; Gordon, 1993; Carrier et al., 1994), parallel (or echelon) swimming (Clark, 1963; Klimley, 1980; Carrier et al., 1994; Harvey-Clark et al., 1999; Sims et al., 2022; Gore et al., 2019), close swimming as described by Gore et al. (2019), and the courtship bite (Stevens, 1974; Pratt, 1979; Pratt and Carrier, 2001; Klimley et al., 2023). The female did not show any indications of acceptance as described by other studies (Gordon, 1993; Pratt and Carrier, 2001). Instead, after the courtship bite, she displayed signs of avoidance by abruptly accelerating away from the male (Pratt and Carrier, 2001; Klimley et al., 2023; Talwar et al. 2023). The inversion of both sharks in the water column has been documented in several shark species during mating activities, including hammerhead, nurse, and reef sharks (Salinas-de-León et al., 2017; Klimley et al., 2023). Typically, in such instances, both sharks cease movement while inverted, facilitating copulation. In this observation, however, copulation did not occur. Instead, the female escaped from the male's bite. This account, therefore, likely represents an unsuccessful mating attempt. Although the observed behaviors strongly resemble typical courtship and mating displays, we interpret this event with caution and refer to it as a putative mating attempt.

Figure 2Exemplary records of female blue sharks with mating scars photographed during shark ecotourism operations. The sharks show scarring on the flank (a, d, e, f), gills (b, e) (1.8 m FL), and pectoral fins (c, f). Multiple (a, d, e, f) and single (b, c) bite marks were documented. More information on the individuals is provided in Table 1.

Documentation of mating behavior in oceanic sharks is rare. However, similar behaviors have been filmed in the oceanic whitetip shark at a similar water depth off Cat Island, Bahamas. Here, putative mating in the water column included following, close swimming, courtship bite, and female avoidance. The behavior was associated with mating scars and hormonal evidence, suggesting the area may serve as a mating habitat (Talwar et al., 2023). Likewise, scalloped hammerhead sharks in the Galapagos have been observed mating in the water column. Copulation occurred after parallel swimming and a courtship bite, with both sharks sinking to the seafloor during the act (Salinas-de-León et al., 2017). These findings support interpreting the current event as a putative mating attempt in blue sharks.

Given the size-at-maturity estimates (Carlson et al., 2023), we likely observed a behavior that has been hypothesized for blue sharks off Nova Scotia, Canada, by Calich and Campagna (2015). In their study, immature females ranging from 1.6 to 2.0 m FL were documented with mating scars from adult males estimated to be 1.8 to 2.6 m FL. Blue sharks have been recorded to be segregated by sex and maturity status, except during mating season (Stevens, 1990; Vandeperre et al., 2014), where males exhibit a tendency to mate with as many females as possible, even if females are immature and as small as 1.4 m FL (Pratt, 1979). We hypothesize that mature males start reproductive attempts with immature females to maximize reproductive success, as has been postulated by other researchers (Pratt, 1979; Calich and Campagna, 2015). Additionally, immature females may be able to store spermatozoa before they reach maturity (Pratt and Carrier, 2011). Hence, mating with immature females may still lead to pregnancies due to delayed fertilization (Pratt, 1993; Dutilloy and Dunn, 2020).

Mating in blue sharks has not been documented in the Northeast Atlantic to date, and reproductive data on the species in the Bay of Biscay are scarce. In this study, several females have been observed with mating scars from June until October. This time period coincides with the known mating season for blue sharks in the Northwest Atlantic (Pratt, 1979). Similarly, blue sharks in the Northwest Pacific were observed with fresh mating scars during spring and summer across large spatial scales ranging from 20 to 40° N (Fujinami et al., 2017). These parallels suggest that the southern Bay of Biscay could represent a potential reproductive area for blue sharks. However, given the opportunistic nature of the dataset, further work combining long-term monitoring, tagging, and reproductive physiology will be essential to establish the ecological importance and spatial scale of this habitat.

This study presents the first visual documentation of putative mating behavior in blue sharks and provides new evidence of mating scars in females within the Bay of Biscay. The observed putative mating interaction and repeated presence of females with mating-associated injuries across multiple years suggest that the continental slope off the Basque coast, northern Spain, may represent a seasonally important reproductive habitat for this species in the Northeast Atlantic. Although the mating attempt was unsuccessful, the sequence of behaviors exhibited aligns with established descriptions of elasmobranch mating interactions. Given the scarcity of fishery-independent data in the Bay of Biscay and the broader knowledge gap regarding blue shark reproductive ecology in the Northeast Atlantic, our findings highlight the ecological significance of this region. However, the demographics in the area, the connectivity to the broader North Atlantic, and their migratory behavior still remain largely unknown. This emphasizes the imminent need for further research efforts on the demographics, habitat use, and reproductive biology of blue sharks in the Bay of Biscay, particularly in relation to conservation and management efforts for this wide-ranging, yet vulnerable, pelagic species. Moreover, the fact that these observations were largely made during ecotourism activities highlights the potential value of responsible ecotourism as a complementary tool for monitoring and conservation.

The data used for this analysis are provided within this paper (see Table 1 and Figs. 1 and 2); no further data were obtained.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/we-25-213-2025-supplement.

LV and LM designed the study and recorded the putative mating behavior. IC photographed the sharks with mating scars during ecotourism operations. ME recorded mating indications during research trips. MS and AR provided a literature review. LV analyzed the data and prepared the article with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We would like to acknowledge the following citizen scientists who made the research expedition, during we documented the putative mating behavior, possible: Johanna Mersmann, Lisa Neher, Michaela Rick, Svenja Rätzsch, Emily Zauner, Sabrina Singer, and Timo Armberger.

This paper was edited by Sergio Navarrete and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Afonso, A. S., Cantareli, C. V., Levy, R. P., Veras, L. B., Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco, Brazil, Instituto Caá-Oby de Conservação e Pesquisa, Brazil, Universidade Santa Cecilia, Brazil, Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Brazil, and Museu dos Tubarões, Brazil: Evasive mating behaviour by female nurse sharks, Ginglymostoma cirratum (Bonnaterre, 1788), in an equatorial insular breeding ground, Neotrop. ichthyol., 14, https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0224-20160103, 2016.

Calich, H. J. and Campana, S. E.: Mating scars reveal mate size in immature female blue shark Prionace glauca, J. Fish Biol., 86, 1845–1851, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.12671, 2015.

Carlson, J., Passerotti, M., and McCandless, C.: Age, growth and maturity of blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the northwest Atlantic Ocean, Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 80, 269–283, 2023.

Carrier, J. C., Pratt, H. L., and Martin, L. K.: Group reproductive behaviour in free-living nurse sharks, Ginglymostoma cirratum, Copeia, 3, 646–656, 1994.

Carrier, J. C., Musick, J. A., and Heithaus, M. R. (Eds.): Biology of sharks and their relatives, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla, 596 pp., https://doi.org/10.1201/b11867, 2004.

Clark, E.: Massive aggregations of large rays and sharks in and near Sarasota, Florida, Zoologica, N.Y., 61–64, 1963.

Compagno, L. J. V. (Ed.): Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Part 2: Carcharhiniformes, FAO Fish. Synop. Rome: FAO, 125, 251-655, http://www.fao.org/docrep/009/ad123e/ad123e00.HTM (last access: 24 October 2025), 1984.

Druon, J.-N., Campana, S., Vandeperre, F., Hazin, F. H. V., Bowlby, H., Coelho, R., Queiroz, N., Serena, F., Abascal, F., Damalas, D., Musyl, M., Lopez, J., Block, B., Afonso, P., Dewar, H., Sabarros, P. S., Finucci, B., Zanzi, A., Bach, P., Senina, I., Garibaldi, F., Sims, D. W., Navarro, J., Cermeño, P., Leone, A., Diez, G., Zapiain, M. T. C., Deflorio, M., Romanov, E. V., Jung, A., Lapinski, M., Francis, M. P., Hazin, H., and Travassos, P.: Global-Scale Environmental Niche and Habitat of Blue Shark (Prionace glauca) by Size and Sex: A Pivotal Step to Improving Stock Management, Front. Mar. Sci., 9, 828412, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.828412, 2022.

Dutilloy, A. and Dunn, M. R.: Observations of sperm storage in some deep-sea elasmobranchs, Deep-Sea Res. I, 166, 103405, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2020.103405, 2020.

Fujinami, Y., Semba, Y., Okamoto, H., Ohshimo, S., and Tanaka, S.: Reproductive biology of the blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the western North Pacific Ocean, Mar. Freshwater Res., 68, 2018–2027, https://doi.org/10.1071/MF16101, 2017.

Gordon, I.: Pre-copulatory behaviour of captive sandtiger sharks, Carcharias taurus, Environ. Biol. Fish. 38, 159–164, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00842912, 1993.

Gore, M., Abels, L., Wasik, S., Saddler, L., and Ormond, R.: Are close-following and breaching behaviours by basking sharks at aggregation sites related to courtship?, J. Mar. Biol. Ass., 99, 681–693, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315418000383, 2019.

Harvey-Clark, C. J., Stobo, W. T., Helle, E., and Mattson, M.: Putative Mating Behavior in Basking Sharks off the Nova Scotia Coast, Copeia, 1999, 780, https://doi.org/10.2307/1447614, 1999.

Johnson, R. H. and Nelson, D. R.: Copulation and possible olfaction-mediated pair information in two species of carcharhinid sharks, Copeia, 3, 539–542, 1978.

Klimley, A. P.: Observations of Courtship and Copulation in the Nurse Shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, Copeia, 1980, 878–882, https://doi.org/10.2307/1444471, 1980.

Klimley, A. P., Porcher, I. F., Clua, E. E. G., and Pratt, H. L.: A review of the behaviours of the Chondrichthyes: a multi-species ethogram for the chimaeras, sharks, and rays, Behav., 160, 967–1080, https://doi.org/10.1163/1568539X-bja10214, 2023.

Kohler, N. E., Turner, P. A., Hoey, J. J., Natanson, L. J., and Briggs, R.: Tag and recapture data for three pelagic shark species: blue shark (Prionace glauca), shortfin mako (Isurus oxyrinchus), and porbeagle (Lamna nasus) in the North Atlantic Ocean, Col. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 54, 1231–1260, 2002.

Linnaeus, C.: Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Editio Decima, Laurentius Salvius, Holmiae (Stockholm), 824 pp., 1758.

McCauley, D. J., Papastamatiou, Y. P., and Young, H. S.: An Observation of Mating in Free-Ranging Blacktip Reef Sharks, Carcbarbinus melanopterus, Pac. Sci., 64, 349–352, https://doi.org/10.2984/64.2.349, 2010.

Pratt, H. L.: Reproduction in the blue shark, Prionace glauca, Fish. B-NOAA, U.S., 77, 445–470, 1979.

Pratt, H. L.: The storage of spermatozoa in the oviducal glands of western North Atlantic sharks, in: The reproduction and development of sharks, skates, rays and ratfishes, vol. 14, edited by: Demski, L. S. and Wourms, J. P., Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht, 139–149, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-3450-9_12, 1993.

Pratt, H. L. and Carrier, J. C.: A Review of Elasmobranch Reproductive Behavior with a Case Study on the Nurse Shark, Ginglymostoma Cirratum, Environ. Biol. Fish., 60, 157–188, 2001.

Pratt, H. L. and Carrier, J. C.: Elasmobranch Courtship and Mating Behavior, In Reproductive biology and phylogeny of Chondrichthyes, CRC press, 129–169 pp., CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla, 2011.

Rohner, C. A., Richardson, A. J., Prebble, C. E., Marshall, A. D., Bennett, M. B., Weeks, S. J., Cliff, G., Wintner, S. P., and Pierce, S. J.: Laser photogrammetry improves size and demographic estimates for whale sharks, PeerJ, 3, e886, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.886, 2015.

Salinas-de-León, P., Hoyos-Padilla, E. M., and Pochet, F.: First observation on the mating behaviour of the endangered scalloped hammerhead shark Sphyrna lewini in the Tropical Eastern Pacific, Environ. Biol. Fish., 100, 1603–1608, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10641-017-0668-0, 2017.

Sims, D. W., Berrow, S. D., O'Sullivan, K. M., Pfeiffer, N. J., Collins, R., Smith, K. L., Pfeiffer, B. M., Connery, P., Wasik, S., Flounders, L., Queiroz, N., Humphries, N. E., Womersley, F. C., and Southall, E. J.: Circles in the sea: annual courtship “torus” behaviour of basking sharks Cetorhinus maximus identified in the eastern North Atlantic Ocean, J. Fish Biol., 101, 1160–1181, https://doi.org/10.1111/jfb.15187, 2022.

Skomal, G. and Natanson, L. J.: Age and growth of the blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the North Atlantic Ocean, Fish. B-NOAA, 101, 627–639, 2003.

Stevens, J. D.: The Occurrence and Significance of Tooth Cuts on the Blue Shark (Prionace Glauca L.) From British Waters, J. Mar. Biol. Ass., 54, 373–378, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400058604, 1974.

Stevens, J. D.: Further results from a tagging study of pelagic sharks in the north-east Atlantic, J. Mar. Biol. Ass., 70, 707–720, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0025315400058999, 1990.

Talwar, B., Bond, M., Williams, S., Brooks, E., Chapman, D., Howey, L., Knotek, R., and Gelsleichter, J.: Reproductive timing and putative mating behavior of the oceanic whitetip shark Carcharhinus longimanus in the eastern Bahamas, Endang. Species. Res., 50, 181–194, https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01231, 2023.

Tricas, T. C. and Le Feuvre, E. M.: Mating in the reef white-tip shark Triaenodon obesus, Mar. Biol., 84, 233–237, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00392492, 1985.

Vandeperre, F., Aires-da-Silva, A., Santos, M., Ferreira, R., Bolten, A. B., Serrao Santos, R., and Afonso, P.: Demography and ecology of blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the central North Atlantic, Fish. Res., 153, 89–102, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2014.01.006, 2014.

Viducic, K., Natanson, L. J., Winton, M. V., and Humphries, A.: Reproductive characteristics for the blue shark (Prionace glauca) in the North Atlantic Ocean, Fish. B-NOAA, 120, 26–38, https://doi.org/10.7755/FB.120.1.3, 2022.