the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Identifying refugia from the synergistic threats of climate change and invasive species

Finnbar Lee

Ian A. K. Kusabs

George L. W. Perry

Calum MacNeil

Climate change may reduce available habitat for native species, while simultaneously increasing suitable habitat for invasive species, which then compete with or predate on native species. Thus, climate change and invasive species can interact synergistically to negatively affect native species. It is important to identify climate refugia that are likely to be both suitable for native species and unsuitable for invasive species, under both present and future climate conditions. We propose a refugia habitat metric (RHM) based on ecological niche modelling. We demonstrate the utility of the metric via a case study of an endemic freshwater crayfish, or kōura (Paranephrops planifrons), which is threatened by both climate change and predation from the invasive brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) in Aotearoa / New Zealand. We used maximum entropy (MaxEnt) ecological niche models to predict current and future habitat suitability for the two species across Aotearoa / New Zealand. By the period 2080–2100, suitable habitat will increase across the northern and western North Island for catfish, while suitable habitat for kōura will decrease overall and shift southwards and towards more mountainous regions. Using the refugia habitat metric, we identified areas of habitat within the current range of kōura, with significant potential refugia habitat outside the species current range. Using the refugia prioritization metric will allow conservation managers to identify habitat for protection and potentially translocation target sites for vulnerable native species.

- Article

(4419 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(88 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Climate change and invasive species can alter biodiversity and ecosystem processes. The impacts of climate change and invasive species are often considered independently, yet these two drivers of global environmental change interact in complex ways, such as enhancing the impacts of invasive species already present by skewing predatory and competitive interactions with natives, if the invader is better adapted to the changing conditions (Rahel et al., 2008). The presence of invasive competitors or predators may result in further declines in native species struggling to adapt to altered climate regimes. Thus, climate change can directly negatively affect a native species and indirectly affect it through facilitating invasive species (Rahel and Olden, 2008).

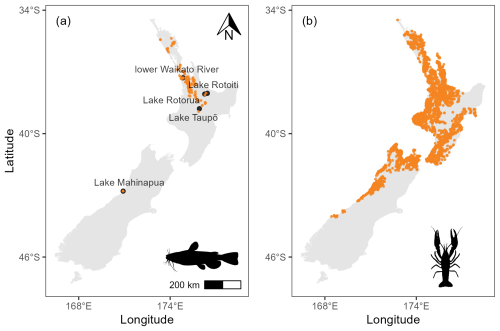

Figure 1(a) Distribution of brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) records in Aotearoa. (b) Distribution of kōura (Paranephrops planifrons) records in Aotearoa. Data from the New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database (Stoffels, 2022).

To identify conditions under which native species are more likely to persist given concurrent climatic change and interactions with introduced species, refugia habitat needs to be identified, ideally within the current range of native species but also further beyond if habitat within the current range becomes unsuitable (Gallardo et al., 2017). Attempts to identify climate change refugia provide an initial filter of environmental suitability (Ashcroft, 2010; Barrows et al., 2020; Keppel et al., 2012). Biotic interactions provide a second level of filtering; for example, the presence of predators or competitors (native and invasive) can reduce suitability, while the presence of prey or host species may be prerequisites for potential refugia (Van Der Putten et al., 2010; Wisz et al., 2013). Identifying all biotic interactions and how they may respond to climate change is effectively impossible, but the presence of invasive species (as a novel competitor, predator, or pathogen) known to threaten native species is likely to be a strong limiting factor to the quality of refugia habitat (McCarthy et al., 2021). Invasive predators in particular can impact lower trophic levels by intensified predator-controlled trophic cascades (Mpanza et al., 2024), which can be the result if refugia of prey are lost, in conjunction with the habitat of predators being sustained or increased. In addition, the presence of invasive predators can have non-consumptive effects on resident prey species, by negatively impacting on feeding, habitat use, and reproduction (MacNeil and Briffa, 2019).

Ecological niche models (ENMs) are widely used to predict the current and potential distribution of species and quantify habitat suitability. Ecological niche models typically use correlations between environmental predictors and species presences and absences (or pseudo-absences or background points) to understand where conditions are most suitable for a species. There are many algorithms available, such as Random Forests, GLM, and MaxEnt, that all make slightly different assumptions but produce relative probability of occurrence or habitat suitability scores (Elith and Leathwick, 2009). Extrapolating ENMs in time or space can be problematic because the assumption of environmental equilibrium may be violated, and novel species interactions and adaptation are not accounted for (Austin, 2007). Nevertheless, extrapolation is essential for conservation planning, and tools exist to quantify issues such as the extent to which extrapolation beyond training data has occurred (Velazco et al., 2024).

Here we address the need to identify refugia from both climate change and invasive species using a novel refugia habitat metric (RHM). We use EMNs to describe current and future habitat suitability for a native and an invasive species. We then use the habitat suitability of the invasive species to down-weight native habitat suitability. Our refugia habitat metric can be used to identify habitats that are both suitable for native species and unsuitable for invasive species. The metric can be applied using current or future environmental and habitat data and can include one or many invasive species. The metric is also agnostic to the modelling approach used to generate habitat suitability scores. We demonstrate the utility of the metric via a case study of an endemic freshwater crayfish, northern kōura (Paranephrops planifrons, hereafter kōura) in Aotearoa / New Zealand (hereafter Aotearoa).

Kōura may be exposed to warming-related stressors and predation by the invasive brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus, hereafter bullhead catfish). Kōura are considered a taonga (treasured) species by Māori (the indigenous people of Aotearoa), and they support important mahinga kai practices (customary food gathering; Kusabs and Quinn, 2009). Kōura occur across much of the North Island of Aotearoa and west of the Southern Alps in the South Island (Fig. 1); they prefer cool, slow-moving water, woody debris cover, and coarse substrates that provide a variety of food items (e.g. invertebrates, plant roots, and leaves) and shelter (Jowett et al., 2008; Kusabs et al., 2015; Parkyn et al., 2002; Usio and Townsend, 2000). Water temperature is an important factor dictating metabolic activity, growth, and feeding behaviour for crayfish (Verhoef and Austin, 1999). In the North Island, kōura have been observed where water temperature ranges from 6–18 °C in streams in native forest cover and from 5–25 °C in pasture streams (Parkyn et al., 2002). Jones (1981) reported the optimum mean daily temperature for kōura to be 19 °C, with a mean critical upper limit of 31.9 °C (Simons, 1984). Freshwater crayfish are vulnerable to climate change via increasing water temperatures and their limited adaptive capacity (Hossain et al., 2018). Kōura are currently declining (their official conservation status is “At Risk: Declining”).

Although population estimates for both kōura and bullhead catfish are uncertain, bullhead catfish are implicated in the decline in kōura in the locations where they have invaded and become established (Clearwater et al., 2014; Dedual, 2019). Although there are few studies in Aotearoa detailing stomach contents of bullhead catfish where kōura are present, Barnes and Hicks (2003) reported that 64 % of large catfish (<250 mm fork length) from rocky shoreline areas of Lake Taupō contained kōura, indicating the catfish is a major predator. Bullhead catfish are native to eastern North America, where they occur in a variety of habitats but particularly in still or slow-moving waterbodies with muddy substrates (Dedual, 2019). The range expansion of bullhead catfish is facilitated by its ability to survive in water temperatures up to 37.5 °C, spawn over a wide temperature range (14–29 °C; Blumer, 1985), and tolerate low oxygen concentrations and poor water quality for prolonged periods and by its broad omnivorous diet (Scott and Crossman, 1973). The bullhead catfish has been present in Aotearoa since 1877, when it was deliberately introduced for sport-fishing (McDowall, 1994). The current distribution of bullhead catfish in Aotearoa is largely confined to the upper North Island (Fig. 1), with only two restricted observations in the South Island (NIWA, 2020); however, in recent decades, the bullhead catfish has expanded its range (Hicks and Allan, 2018). Until 1985, the bullhead catfish was restricted to the lower parts of the Waikato River in the North Island and to Lake Mahinapua in the South Island (Fig. 1). In 1985, it was detected in Lake Taupō (Barnes and Hicks, 2003). It has since spread throughout the Waikato River and has reached lakes nearly 100 km to the northeast in the Rotorua region (lakes Rotorua and Rotoiti in 2016 and 2018, respectively) and multiple catchments in the north of the North Island (Hicks and Allan, 2018).

In Aotearoa, many freshwater native fish could face extinction or near-extinction from loss of viable habitat due to climate change (Canning et al., 2025), which will be exacerbated by interactions with other stressors, such as declining water quality and non-climate-related habitat loss (Ling, 2010). Given the broader temperature tolerances of bullhead catfish than kōura, and projected increases in temperature for Aotearoa under climate change, kōura face compounding pressures from climate change itself (NIWA 2020) and from a highly invasive predator favoured by such change. Climate change is likely to result in a net decrease in suitable habitat for kōura and a net increase in suitable habitat for bullhead catfish. Here, we describe the RHM, illustrate how habitat suitability for kōura and bullhead catfish is likely to change by the end of the century, and apply the RHM to identify a potential refugia habitat for kōura.

Firstly, we describe the RHM mathematically, along with its key properties. We then use ecological niche models to identify suitable habitat across Aotearoa for bullhead catfish and kōura for the present day and under predicted climate conditions for 2080–2100. We then calculate RHM scores for Aotearoa to identify potential current and future refugia for kōura.

2.1 Refugia habitat metric

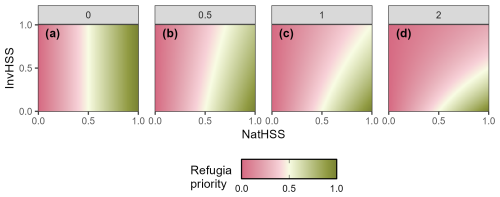

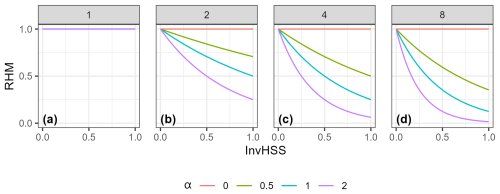

Refugia habitat metric (RHM) scores were calculated using habitat suitability maps produced via ecological niche modelling (explained below), where each raster pixel has a habitat suitability score ranging from 0–1 (0 unsuitable – 1 suitable). Habitat suitability maps are required for the native species and the n invasive species of interest. The RHM can only be calculated for pixels that have a score for all species of interest. The fundamental concept behind the RHM is that habitat suitability for the native species should be down-weighted based on the habitat suitability score(s) of invasive species. We chose to use a negative exponential weighting, as we assumed the presence of an increasing number of invasive species would have a diminishing effect on the native species. Firstly, a weighting parameter (ω) was calculated based on the habitat suitability score(s) of invasive species:

where InvHSSi is the habitat suitability score of the ith invasive species in each pixel, n is the total number of invasive species, and αi describes the strength of interactions between the ith invasive species and the native species. Higher values of αi indicate that high habitat suitability scores for the invasive species should more strongly negatively affect the habitat suitability scores of the native species. An αi of 0.0 results in an invasive species having no effect on the RHM (RHM = NatHSS). An αi of 1.0 can be used by default. The RHM was then calculated by reweighting the native species' habitat suitability score:

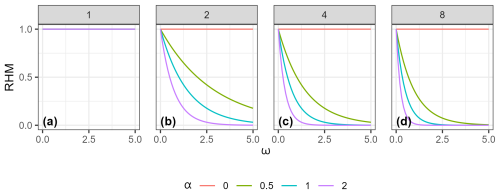

Figure 2Example of how the RHM responds to the invasive species habitat suitability score (InvHSS) for a range of invasive species habitat suitability score weighting parameter (α) values (a: 0; b: 0.5; c: 1; d: 2) when a single invasive species is present. β fixed at 2.0.

Figure 3Example of how the RHM responds to the invasive species habitat suitability score (InvHSS) for a range of invasive species habitat suitability score weighting parameter (α) values and shape parameter (β) values (a: 1; b: 2; c: 4; d: 8) when a single invasive species is present. All values of NatHSS were fixed at 1.0. See Fig. A1 for the equivalent figure but with multiple invasive species.

where NatHSS is the habitat suitability score of the native species in a given pixel and β is a global weighting parameter. Values of β must be 1.0 (all invasive species have no effect on native species) or greater. The RHM metric has the following properties:

-

It ranges between 0.0 and 1.0.

-

If the invasive species has a habitat suitability score of 0.0, the NatHSS is equal to the RHM.

-

If α is 0.0, the NatHSS is equal to the RHM.

-

If β is 1.0, the NatHSS is equal to the RHM.

-

If α = 1, β = 2, and ω = 1, the RHM = NatHSS/2. We recommend α = 1 and β = 2 as the default values.

-

There is no limit to the number of invasive species that can be included.

-

Down-weighting follows a negative exponential relationship; that is, as ω increases, the relative effect on the RHM deceases. (Figs. 3 and A1).

2.2 Case study: endemic kōura and invasive bullhead catfish

2.2.1 Species records

Occurrence records for bullhead catfish and kōura were downloaded from the New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database (NZFFD; Stoffels, 2022). Occurrence data were filtered to include records from 1986 onwards, to align with environmental data (see Sect. 2.2.2 for description of environmental data). Data were cleaned by removing duplicates and the following records: those within 1 km of country centroids, those within 1 km of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) headquarters in Copenhagen, those within 100 m of known biodiversity institutions (these coordinates emerge via automation when just the country is listed in the primary source; Zizka et al., 2019), and those located in the sea or at 0,0 longitude/latitude (Zizka et al., 2019). We only included “human observation” records (i.e. we discarded museum specimens, individuals at zoos, and other non-observation records). After these filters were applied, we were left with 7344 occurrence points (native range = 5766; introduced = 1578; Fig. 1). The NZFFD does not distinguish between Northern (Paranephrops planifrons) and Southern kōura (P. zealandicus; the only other crayfish species in Aotearoa); however, the records can be distinguished due to the two species maintaining distinct geographic ranges (Hopkins, 1970). After filtering the occurrence records, we were left with 255 and 3654 presences for bullhead and kōura, respectively (Fig. 1).

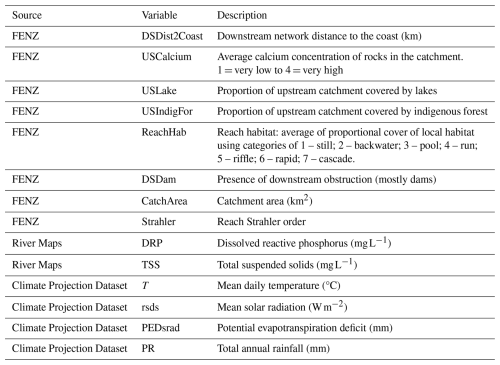

2.2.2 Environmental variables

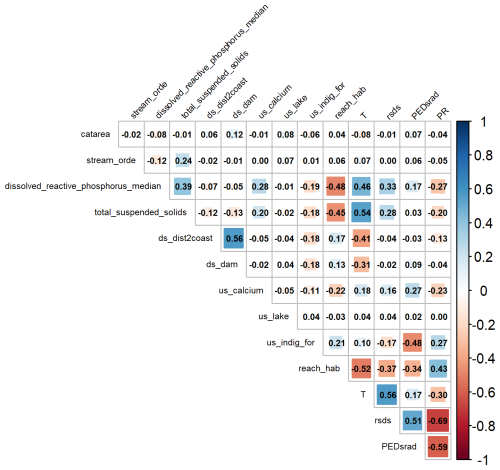

We focused on environmental and habitat variables that are ecologically important to freshwater species (Table A1). We included river-specific variables from the Freshwater Environments of New Zealand (FENZ) database. FENZ consists of a network representing all river reaches in Aotearoa, and it contains over 500 000 individual reaches (Leathwick et al., 2010). Each reach is described in terms of a series of modelled physiochemical variables such as upstream forest cover and reach slope. From the FENZ database we included the following variables: catchment area, Strahler order, median, downstream distance to the coast, upstream calcium concentration, proportion upstream catchment covered by lakes, upstream indigenous forest cover, and reach habitat type (1 = still; 2 = backwater; 3 = pool; 4 = run; 5 = riffle; 6 = rapid; 7 = cascade). Additionally, we included dissolved reactive phosphorus (DRP; Whitehead et al., 2022) and total suspended solids (TSS; Unwin and Larned, 2013) from the River Maps database (Whitehead and Booker, 2019). There are no future predictions available for the FENZ variables; therefore we assumed they would remain relatively static through time. We included ecologically important climate variables (mean daily temperature, total annual rainfall, mean solar radiation, and potential evapotranspiration deficit) from the New Zealand Climate Projection Dataset for the period 1986–2005 (Gibson et al., 2024). Air temperature variables were used as surrogates for instream temperature, as instream temperature data were not available and air temperature is correlated with instream temperature (McGarvey et al., 2018). The data have been downsampled at 5 km resolution specifically for Aotearoa from global models. Since the FENZ data were in vector format and the climate data were gridded raster data, we extracted climate data along each FENZ reach; if a reach intersected more than one grid pixel, we took the mean value across intersecting pixels. All absolute pairwise correlations among environmental variables were less than 0.7. Predictors were not transformed prior to analysis.

To understand how habitat suitability is likely to change later this century, we used projections for mean daily temperature, total annual rainfall, mean solar radiation, and potential evapotranspiration deficit for the period 2080–2100 from the New Zealand Climate Projection Dataset, which consists of climate projections created using six global models downscaled to provide New Zealand-specific projections at a 5 km grid. Given the uncertainty in future climate projections, we used mean estimates derived from the six models (NorESM2-MM, AWI-CM-1-1-MR, GFDL-ESM4, ACCESS-CM2, EC-Earth3, CNRM-CM6-1) for the Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) SSP3-7.0 scenario (Gibson et al., 2024). We have assumed the non-climate predictors will not change into the future, which is likely a best-case scenario for kōura; the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management 2020, which is the current overriding freshwater environmental protection legislation in Aotearoa / New Zealand, sets out the requirements that ecosystem health of water bodies must be either maintained or improved, which provides some justification for this assumption.

2.2.3 Ecological niche modelling

To predict habitat suitability across Aotearoa for bullhead catfish and kōura, we implemented a maximum entropy (MaxEnt) model (Phillips et al., 2006). MaxEnt is a presence–background approach based on an inhomogeneous Poisson process specifically designed for presence-only data (Phillips et al., 2017). We used MaxEnt due to its high predictive performance when using presence-only data and when looking to extrapolate in space or time (Ahmadi et al., 2023; Heikkinen et al., 2012; Valavi et al., 2022; Velazco et al., 2024).

When creating a calibration area for presence-only models, it is important to delineate areas where species have had the opportunity to colonize (Barve et al., 2011); therefore we constrained the calibration area to catchments that contained at least one occurrence record. We sampled 10 000 background reaches at random from within calibration areas (Hill et al., 2017; Merow et al., 2013).

We systematically varied the hyper-parameter settings to tune the MaxEnt model and tested regularization multiplier settings of 0.5, 1, 2, and 3 and feature class settings of linear (“l”), hinge (“h”), quadratic (“q”), product (“p”), and threshold (“t”). The hyper-parameter combination that maximized the true skill statistic (TSS) was selected, and the final model had the regularization multiplier set to 2.0 and 0.5 for bullhead catfish and kōura, respectively, and feature class combination “lhp” for both species.

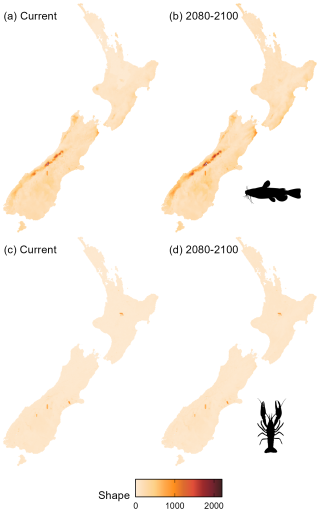

Model discrimination was assessed using K-fold cross-validation (N=5). Firstly, we used the area under the receiver operator curve (AUC), where values range from 0 to 1, with a value of 0.5 indicating no better than random predictive ability and a value of 1 indicating perfect prediction (Fielding and Bell, 1997). Secondly, we used the Continuous Boyce Index (CBI), which is favoured in studies that use presence-only data and where values range from −1 to 1, with higher values indicating better performance. Thirdly, we calculated sensitivity, specificity, and the true skill statistic (TSS), where values closer to 1.0 indicate better model discrimination. Because we extrapolated habitat suitability to areas and times outside the training data, we quantified the degree of extrapolation in environmental space between the training and projection data, using the shape metric (Velazco et al., 2024). Shape is calculated using the multivariate distance from each extrapolated point to the nearest training data point, in environmental space. If a given extrapolated point has a shape value of 100, it is 100 times further away from the nearest training data point than the averaged Mahalanobis distance between training data points and the centroid of the training data (Velazco et al., 2024). Non-analogue environments do not necessarily equate to invalid predictions, since invasive species have often shown their ability to colonize new environments, but identify areas where predictions may be uncertain.

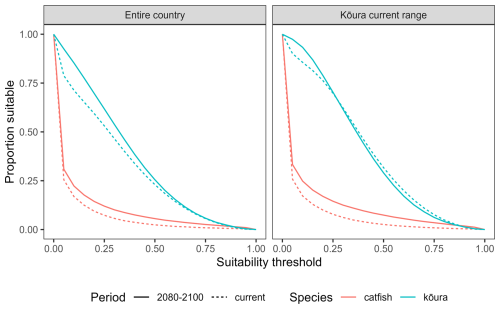

To understand how the amount of habitat available to kōura and bullhead catfish is likely to change between now and 2080–2100 and to avoid having to pick a single binarizing threshold, we calculated total available habitat for the two time periods across the full range of binarizing thresholds (0–1). Finally, we calculated the RHM for current and future time periods. All analysis was carried out in R v.4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2020). We used the tidyverse v2.0.0 (Wickham et al., 2019), terra v1.8.54 (Hijmans, 2024), and sf v1.0.21 (Pebesma, 2018) packages for data manipulation; the flexsdm v1.3.6 (Velazco et al., 2022) package for model fitting; and the tidyterra v0.7.2 (Hernangómez, 2023) and patchwork v1.3.1 (Pedersen, 2021) packages for visualization.

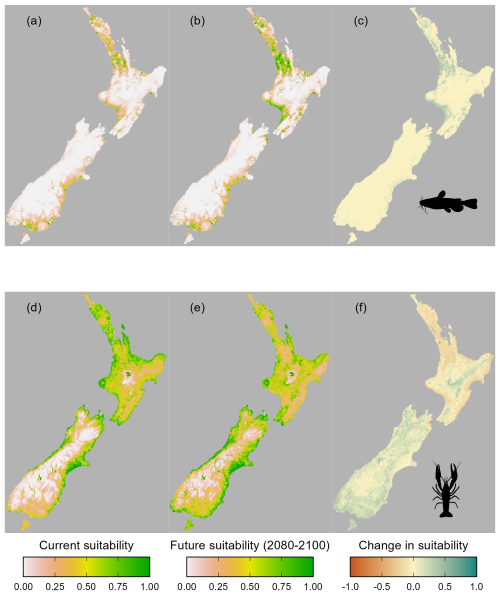

Figure 4Predicted habitat suitability of Aotearoa for (a–c) brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) and (d–f) kōura (Paranephrops planifrons) under current climatic conditions (a, d) and in the period 2080–2100 (b, e), with the change in suitability between current and future conditions (c, f).

3.1 Current and future habitat suitability

The accuracy of the MaxEnt models varied for bullhead catfish and kōura (AUC = 0.92, CBI = 0.92, sensitivity = 0.92, specificity = 0.78, true skill statistic = 0.70 for bullhead catfish; AUC = 0.81, CBI = 0.99, sensitivity = 0.73, specificity = 0.73, true skill statistic = 0.46 for kōura). Currently, from known species records, bullhead catfish are largely confined to the upper North Island, and our habitat suitability modelling confirmed the northern and to a lesser extent the western North Island are highly suitable for bullhead catfish, while in the South Island there are small areas of suitability, particularly along the east and south of the island (Fig. 4). For kōura, known records show this currently occurring across much of the North Island and west of the Southern Alps in the South Island, and our habitat suitability modelling confirmed much of coastal Aotearoa had good to high (greater than 0.5) habitat suitability. For both bullhead catfish and kōura, the mountainous central South Island and eastern North Island had low suitability. Under future climate scenarios, bullhead catfish habitat suitability either remained similar to current conditions or increased in suitability for the period 2080–2100 (Fig. 4). Furthermore, there were significant increases in habitat suitability, particularly in the western North Island. In contrast, for kōura, habitat suitability declined across most of the current range in the North Island, with the South Island range maintaining high suitability. Outside of the current range, the South Island largely increased in suitability, as did the central and eastern North Island (Fig. 4). Overall, under climate change, the amount of Aotearoa favourable for kōura is projected to stay relatively stable but with shifts in where is suitable, while for catfish there is an overall increase in habitat suitability (Figs. 4 and 5).

Environmental conditions in the South Island were less similar to model training data than conditions in the North Island, as indicated by higher shape values (measure of environmental dissimilarity between training and extrapolated data) for bullhead catfish, indicating a greater level of uncertainty in model projections in the South Island. In contrast, for kōura, most areas had low (< 50) shape values, which is unsurprising given that the projection and training areas overlapped significantly (Fig. A3).

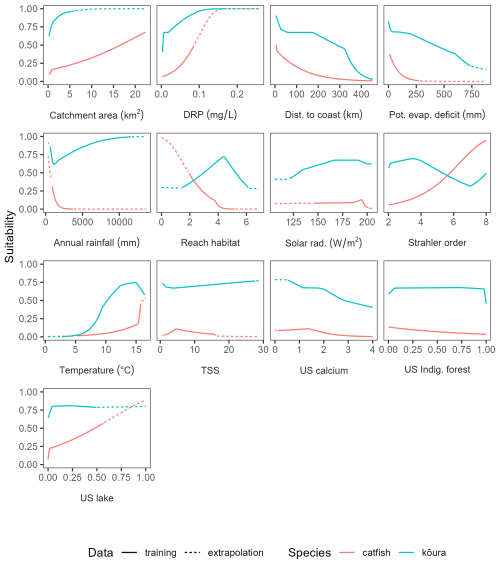

Figure 6Partial dependence plots for the MaxEnt model predicting habitat suitability of Aotearoa for brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) and kōura (Paranephrops planifrons).

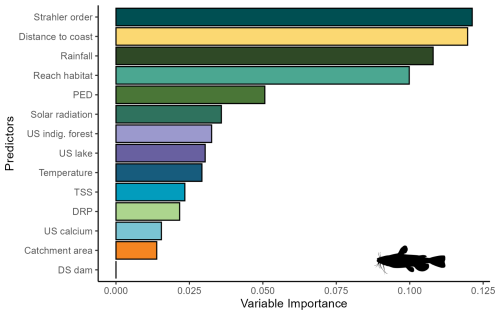

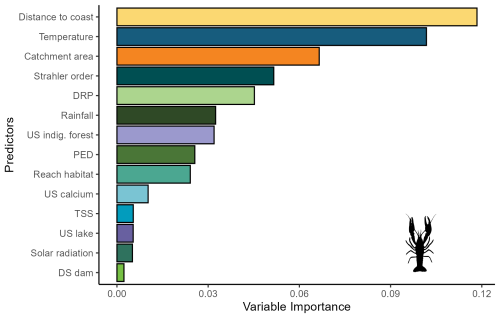

For bullhead catfish, the most important predictors of habitat suitability were distance to coast, Strahler order, annual rainfall, and reach habitat (Fig. A4); for kōura, they were distance to coast, mean annual temperature, catchment area, and Strahler order (Fig. A5). On average, higher habitat suitability scores for bullhead catfish were associated with low distance to coast, high Strahler stream order (larger rivers), low annual rainfall, low habitat scores (still water/backwater habitats), and higher mean annual temperature (Fig. 6). Kōura habitat suitability was positively associated with low distance to coast, intermediate temperatures, larger catchments, and low Strahler order (smaller streams; Fig. 6).

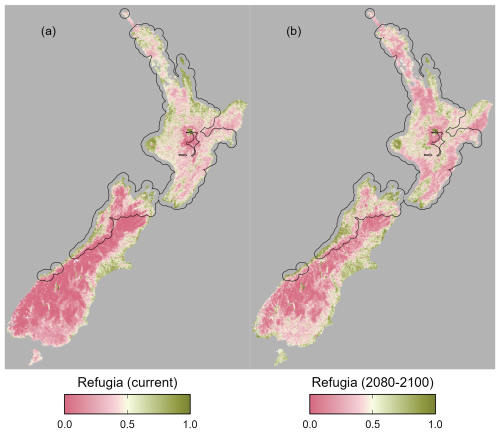

Figure 7Potential refugia (0 low priority, 1 high priority) for kōura (Paranephrops planifrons) based on current and future habitat suitability for kōura and brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus), for current (a) and future (b) conditions. Black polygons indicate kōura occurrences with a 20 km buffer, approximating the current distribution.

3.2 Refugia habitat metric

The refugia habitat metric indicates that under current conditions there are significant areas of high-suitability refugia in the current range of kōura, particularly in the western and southern North Island and across the north and west of the South Island (Fig. 7a). Additionally, there is significant refugia habitat outside the species current range, across the eastern South Island. Under future conditions, potential refugia habitat contracts, particularly within the current range in the northern North Island, although significant refugia still remain in the western North Island and South Island (Fig. 7b). There is also significant refugia habitat present outside the current range in the eastern South Island.

The RHM introduced in this study represents an advancement in ecological niche modelling by integrating the influence of invasive species into projections of native species' habitat suitability under climate change. While most ENMs focus on abiotic predictors of habitat suitability, such as temperature and precipitation (Elith and Leathwick, 2009), they often overlook the role of biotic interactions (but see Pollock et al., 2014, for a description for joint species distribution models). By down-weighting the native species' habitat suitability in areas with high invasive species habitat suitability, the RHM accounts for a key ecological constraint on native persistence. Our approach explicitly acknowledges that habitat suitability is not solely a function of environmental drivers but also biotic interactions (Araújo and Luoto, 2007). The RHM offers a flexible and scalable approach that directly modifies the native species' suitability surface based on invasion potential, producing maps that simultaneously reflect abiotic and biotic constraints. The RHM is not intended to replace existing tools but rather to complement and enhance them. If used alongside mechanistic models, physiological threshold data, or population viability analyses, the metric could help provide a more complete picture of species persistence potential. Furthermore, integrating it with landscape connectivity or habitat fragmentation models could identify corridors that facilitate native species' movement to less invaded and climatically stable areas. Taking a multi-pronged approach would allow a more comprehensive conservation strategy that considers both environmental and ecological dimensions of habitat suitability.

Although we used brown bullhead catfish and northern kōura in our case study, the RHM is designed to be broadly applicable across taxonomic groups, ecosystem types, and geographic scales. It can be used in the context of different invasive pressures, from aggressive plant species to aquatic invaders disrupting native fish assemblages. As long as ENMs can be developed for both native and invasive species, the metric can identify refugia in terrestrial, freshwater, or marine systems. Moreover, the approach is scalable: it can be applied locally for site-level management or extended to regional or global biodiversity assessments (Thuiller et al., 2005; Tingley et al., 2014). This flexibility makes the RHM applicable to a wide range of ecological and conservation contexts, from targeted reserve design to continental-scale invasion risk mapping.

From a practical standpoint, the metric provides a valuable tool for conservation managers and policymakers tasked with navigating the complex realities of global change (Rillig, 2025). By identifying areas that are likely to offer both climatic stability and low invasion pressure, the RHM can help focus efforts where native species are most likely to persist. This has direct applications in habitat restoration, reserve design, and invasive species management and could guide assisted migration efforts, especially where funding or capacity is limited (Heller and Zavaleta, 2009). The metric could also inform spatial prioritization in national biodiversity strategies or contribute to global assessments of climate refugia (Morelli et al., 2016). Moreover, it aligns with emerging conservation frameworks that advocate for proactive, integrated approaches that address multiple drivers of biodiversity loss simultaneously (IPBES, 2019). With the recent (2023) invasion of the freshwaters of Aotearoa / New Zealand by the gold/Asian clam (Corbicula fluminea), an ecosystem engineer with the potential to outcompete and replace culturally valued native bivalves (Somerville et al., 2025), conservation translocations involving moving native species out of the pathway of the ongoing range expansion of such potentially damaging invaders is a current subject of debate within government proception agencies (MPI, 2023). The RHM could provide a highly useful and practical conservation tool in these endeavours.

While the RHM is a useful tool for identifying areas where native species may face less intense invasion pressure, it is important to consider the limitations of ecological assumptions underpinning its design. Firstly, the metric assumes that areas of high suitability for invasive species are associated with greater ecological risk to natives, primarily through competitive displacement or predation. However, this relationship is likely context-dependent, varying with species traits, resource overlap, and environmental conditions (Lee-Yaw et al., 2022; MacDougall et al., 2009). For example, the effects of catfish on kōura are likely to be greatest where eels (Anguilla dieffenbachia and A. australis) are not present or are rare (e.g. Rotorua and Taupō lakes); where eels are abundant, they generally dominate catfish, reducing their effect on kōura (Kusabs pers. obs.). Some introduced species may have minimal impact on certain native taxa despite co-occurrence, while others may be highly disruptive even at low densities (Ricciardi et al., 2013), highlighting the need for input from experts when deciding which invasive species to include in the modelling or how to weight different species. Secondly, the relative effect of invasive species may be context-dependent. For instance, in one of the few Aotearoa / New Zealand studies detailing stomach contents of bullhead catfish in invaded areas harbouring significant kōura populations, the stomach contents of 6247 catfish from Lake Taupō revealed that 64 % of large catfish (<250 mm fork length) from rocky shoreline areas contained kōura, while only 15 % of the same-size catfish from weedy areas of shoreline contained kōura (Barnes and Hicks, 2003). This indicates the importance of the habitat template in which the interaction is taking place in determining if the invader is “weak” or “strong” in terms of predatory impact (Kumschick et al., 2011). A strength of the RHM is the ability to incorporate variability in the effect of different invasive species via the α parameter (although determining α values may be challenging if one wants to move beyond qualitative rankings of invasive species impacts). Thirdly, the reliability of the RHM is contingent on the quality of the underlying ENMs. The ENM approach is biologically naive and ignores dispersal limitation and multi-species interactions (Wisz et al., 2013). For example, the area invaded by catfish may be less than that predicted by the model due to dispersal limitation and human interventions (e.g. eradication efforts). Ultimately, if all these mechanisms are to be included, more process-based models are required (Pilowsky et al., 2022). Furthermore, model outputs are influenced by the resolution and quality of environmental predictors, the choice of algorithms, and the completeness of occurrence data (Elith and Graham, 2009). For example, the river reaches in our case study are approximately 700 m in length, which will not capture microhabitat refugia, such as small headwater and spring-fed streams, and which will allow kōura to persist within their current range (Clearwater et al., 2014). Fourthly, the RHM is static and does not account for temporal dynamics such as lagged responses to climate change or adaptive evolution in native species. These limitations highlight the importance of using the metric as a component of an integrative framework, rather than a stand-alone predictive tool. Finally, uncertainties inherent in climate projections, land-use scenarios, or invasive species distributions can propagate non-additively (Buisson et al., 2010). Sensitivity analyses and ensemble modelling could help quantify and mitigate some of these uncertainties, but users of the RHM should remain cautious and transparent about potential sources of error.

Future work could integrate dynamic modelling frameworks (e.g. process-based or agent-based models) or couple the metric with trait-based or mechanistic approaches that better capture species-specific vulnerabilities and adaptive capacities (Kearney and Porter, 2009; Pilowsky et al., 2022). Incorporating temporal dynamics, such as simulating invasive species' spread rates or native species' dispersal abilities, would allow more realistic projections under changing environmental conditions. Validation of the RHM represents a next step for advancing its application and credibility. Empirical testing could involve comparing adjusted suitability predictions to known patterns of native persistence or decline in the presence of invasive species across environmental gradients. Long-term monitoring data, experimental removals, and invasion chronosequences offer valuable opportunities to test whether areas identified as dual refugia correspond with higher native survival or reproductive success. These directions represent promising avenues for future research and development.

Finally, in the bullhead catfish – kōura case study, we showed that significant parts of the North Island and parts of the eastern South Island of Aotearoa are predicted to become suitable for bullhead catfish under climate change. The predictions across the North Island are similar to those predicted in Canning et al. (2025), although they did not predict any suitable habitat in the South Island. For kōura, climate change is predicted to have mixed effects; some parts of Aotearoa will become more suitable, while others will become less suitable. Areas of increasing habitat suitability are concentrated in the cooler southern parts of the country, whereas habitat suitability decreased in northern lowland coastal areas, which, while currently suitable, may become too warm in the future. Bullhead catfish pressure is likely to be greatest (i) in shallow lakes/rivers where the bed substrate is composed mainly of sand/mud and (ii) in lakes that suffer from hypolimnetic deoxygenation; in these waterbodies, kōura have very limited, if any, rocky habitat or depth refugia from bullhead catfish (Francis, 2019). As discussed earlier, there are likely to be refugia within the current range of kōura, in the form of small headwater and spring-fed streams which were not necessarily identified here given the fine-resolution data that are needed to tease apart microhabitat variability. Many of these systems have large kōura populations and could easily be engineered to exclude predators, for example, using weirs (Ian A. K. Kusabs, personal observation). It is unlikely that kōura will be able to track refugia outside their current range given dispersal constraints. For example, the area extending northeast from Rotorua–Taupō (eastern North Island) has large areas of potentially suitable habitat, yet kōura are absent. McDowall (2005) hypothesized that this gap in the distribution is due to dispersal limitation and a failure to recolonize the area after volcanic eruptions locally extirpated kōura populations (McDowall, 2005). Translocations are increasing being considered for freshwater conservation in Aotearoa / New Zealand (Rayne et al., 2025) and provide one approach to facilitate climate tracking. For kōura there is an existing long history of translocating for fisheries purposes (Rayne et al., 2020).

We have developed and demonstrated the use of a novel metric to identify habitat refugia from the combined threats of climate change and invasive species. The RHM has the potential to be used in a wide variety of conservation settings and should be beneficial to species managers and restoration practitioners.

Figure A1Example of how the RHM responds to multiple invasive species (ω) for a range of invasive species habitat suitability score weighting parameter (α) values and shape parameter (β) values (a: 1; b: 2; c: 4; d: 8). All values of NatHSS were fixed at 1.0.

Table A1Description of the environmental and climate variables used in the MaxEnt models of brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) and kōura (Paranephrops planifrons) habitat suitability.

Figure A2Pairwise correlations among environmental predictors used in MaxEnt models for brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) and kōura (Paranephrops planifrons) habitat suitability. See Table A1 for a description of variables.

Figure A3Shape metric scores across Aotearoa for kōura (Paranephrops planifrons) and brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus). “2080–2100” refers to the SSP3-7.0 Shared Socioeconomic Pathway projection for the period 2080–2100.

Modelling code and the prepared input datasets are accessible in an open repository (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17372820; Lee, 2025). An implementation of the RHM is provided in an R script in the Supplement.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/we-25-221-2025-supplement.

FL, CM, and GLWP conceived the study. FL conducted the analyses and wrote the first draft. All authors contributed critically to the drafts and gave final approval for publication.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

The authors thank the two anonymous reviewers whose feedback greatly improved the quality and clarity of the article. We also thank Joanne Clapcott who provided feedback on the draft, along with everyone who contributed data to the New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database.

This research has been supported by the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment (grant no. CAWX2101).

This paper was edited by Adrian Brennan and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Ahmadi, M., Hemami, M., Kaboli, M., and Shabani, F.: MaxEnt brings comparable results when the input data are being completed; Model parameterization of four species distribution models, Ecol. Evol., 13, e9827, https://doi.org/10.1002/ece3.9827, 2023.

Araújo, M. B. and Luoto, M.: The importance of biotic interactions for modelling species distributions under climate change, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 16, 743–753, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00359.x, 2007.

Ashcroft, M. B.: Identifying refugia from climate change, J. Biogeogr., 37, 1407–1413, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02300.x, 2010.

Austin, M.: Species distribution models and ecological theory: a critical assessment and some possible new approaches, Ecol. Model., 200, 1–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2006.07.005, 2007.

Barnes, G. E. and Hicks, B. J.: Brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) in Lake Taupo, Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand, 2003.

Barrows, C. W., Ramirez, A. R., Sweet, L. C., Morelli, T. L., Millar, C. I., Frakes, N., Rodgers, J., and Mahalovich, M. F.: Validating climate-change refugia: empirical bottom-up approaches to support management actions, Front. Ecol. Environ., 18, 298–306, https://doi.org/10.1002/fee.2205, 2020.

Barve, N., Barve, V., Jiménez-Valverde, A., Lira-Noriega, A., Maher, S. P., Peterson, A. T., Soberón, J., and Villalobos, F.: The crucial role of the accessible area in ecological niche modeling and species distribution modeling, Ecol. Model., 222, 1810–1819, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2011.02.011, 2011.

Blumer, L. S.: Reproductive natural history of the brown bullhead Ictalurus nebulosus in Michigan, Am. Midl. Nat., 318–330, https://doi.org/10.2307/2425607, 1985.

Buisson, L., Thuiller, W., Casajus, N., Lek, S., and Grenouillet, G.: Uncertainty in ensemble forecasting of species distribution, Glob. Change Biol., 16, 1145–1157, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2009.02000.x, 2010.

Calabrese, J. M., Certain, G., Kraan, C., and Dormann, C. F.: Stacking species distribution models and adjusting bias by linking them to macroecological models, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 23, 99–112, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12102, 2014.

Canning, A. D., Zammit, C., and Death, R. G.: The implications of climate change for New Zealand's freshwater fish, Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci., 82, 1–15, https://doi.org/10.1139/cjfas-2024-0127, 2025.

Clearwater, S. J., Kusabs, I., Budd, R., and Bowman, E.: Strategic evaluation of kōura populations in the upper Waikato River, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, Hamilton, New Zealand, 2014.

Dedual, M.: Summary of the impacts and control methods of Brown Bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus Lesueur 1815) in New Zealand and overseas, Environment Bay of Plenty, MD-halieutics, New Zealand, https://atlas.boprc.govt.nz/api/v1/edms/document/A3591759/content (last access: July 2024), 2019.

Elith, J. and Graham, C. H.: Do they? How do they? WHY do they differ? On finding reasons for differing performances of species distribution models, Ecography, 32, 66–77, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05505.x, 2009.

Elith, J. and Leathwick, J. R.: Species distribution models: ecological explanation and prediction across space and time, Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst., 40, 677–697, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159, 2009.

Fielding, A. H. and Bell, J. F.: A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models, Environ. Conserv., 24, 38–49, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892997000088, 1997.

Francis, L.: Evaluating the effects of invasive brown bullhead catfish (Ameiurus nebulosus) on kōura (freshwater crayfish, Paranephrops planifrons) in Lake Rotoiti, Thesis, Master of Science, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, https://hdl.handle.net/10289/12746 (last access: June 2024), 2019.

Gallardo, B., Aldridge, D. C., González-Moreno, P., Pergl, J., Pizarro, M., Pyšek, P., Thuiller, W., Yesson, C., and Vilà, M.: Protected areas offer refuge from invasive species spreading under climate change, Glob. Change Biol., 23, 5331–5343, https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13798, 2017.

Gibson, P. B., Stuart, S., Sood, A., Stone, D., Rampal, N., Lewis, H., Broadbent, A., Thatcher, M., and Morgenstern, O.: Dynamical downscaling CMIP6 models over New Zealand: added value of climatology and extremes, Clim. Dynam., 62, 8255–8281, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00382-024-07337-5, 2024.

Heikkinen, R. K., Marmion, M., and Luoto, M.: Does the interpolation accuracy of species distribution models come at the expense of transferability?, Ecography, 35, 276–288, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2011.06999.x, 2012.

Heller, N. E. and Zavaleta, E. S.: Biodiversity management in the face of climate change: a review of 22 years of recommendations, Biol. Conserv., 142, 14–32, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.10.006, 2009.

Hernangómez, D.: Using the tidyverse with terra objects: the tidyterra package, J. Open Source Softw., 8, 5751, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.05751, 2023.

Hicks, B. J. and Allan, M. G.: Estimation of potential contributions of brown bullhead catfish to the nutrient budgets of lakes Rotorua and Rotoiti, Environmental Research Institute, The University of Waikato, Hamilton, 2018.

Hijmans, R. J.: terra: Spatial Data Analysis, R package version 1.7-78, Comprehensive R Archive Network, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=terra (last access: August 2025), 2024.

Hill, M. P., Gallardo, B., and Terblanche, J. S.: A global assessment of climatic niche shifts and human influence in insect invasions, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 26, 679–689, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12578, 2017.

Hopkins, C. L.: Systematics of the New Zealand freshwater crayfish Paranephrops (Crustacea: Decapoda: Parastacidae), N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 4, 278–291, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.1970.9515347, 1970.

Hossain, M. A., Lahoz-Monfort, J. J., Burgman, M. A., Böhm, M., Kujala, H., and Bland, L. M.: Assessing the vulnerability of freshwater crayfish to climate change, Divers. Distrib., 24, 1830–1843, https://doi.org/10.1111/ddi.12831, 2018.

IPBES: Global assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, edited by: EBrondizio, E. S., Settele, J., Díaz, S., and Ngo H. T., IPBES secretariat, Bonn, Germany, https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3831673, 1148 pp., 2019.

Jones, J. B.: Growth of two species of freshwater crayfish ( Paranephrops spp.) in New Zealand, N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 15, 15–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.1981.9515892, 1981.

Jowett, I. G., Parkyn, S. M., and Richardson, J.: Habitat characteristics of crayfish (Paranephrops planifrons) in New Zealand streams using generalised additive models (GAMs), Hydrobiologia, 596, 353–365, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10750-007-9108-z, 2008.

Kearney, M. and Porter, W.: Mechanistic niche modelling: combining physiological and spatial data to predict species' ranges, Ecol. Lett., 12, 334–350, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01277.x, 2009.

Keppel, G., Van Niel, K. P., Wardell-Johnson, G. W., Yates, C. J., Byrne, M., Mucina, L., Schut, A. G. T., Hopper, S. D., and Franklin, S. E.: Refugia: identifying and understanding safe havens for biodiversity under climate change, Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr., 21, 393–404, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00686.x, 2012.

Kumschick, S., Alba, C., Hufbauer, R. A., and Nentwig, W.: Weak or strong invaders? A comparison of impact between the native and invaded ranges of mammals and birds alien to Europe, Divers. Distrib., 17, 663–672, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2011.00775.x, 2011.

Kusabs, I. A. and Quinn, J. M.: Use of a traditional Maori harvesting method, the tau kōura, for monitoring kōura (freshwater crayfish, Paranephrops planifions) in Lake Rotoiti, North Island, New Zealand, N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 43, 713–722, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330909510036, 2009.

Kusabs, I. A., Hicks, B. J., Quinn, J. M., and Hamilton, D. P.: Sustainable management of freshwater crayfish (kōura, Paranephrops planifrons) in Te Arawa (Rotorua) lakes, North Island, New Zealand, Fish. Res., 168, 35–46, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2015.03.015, 2015.

Leathwick, J., West, D., Gerbeaux, P., Kelly, D., Robertson, H., Brown, D., Chadderton, W. L., and Ausseil, A. G.: Freshwater Ecosystems of New Zealand (FENZ) Geodatabase, Department of Conservation, 2010.

Lee, F.: Catfish and kōura data and R code, Zenodo [code and data set], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17372820, 2025.

Lee-Yaw, J., L. McCune, J., Pironon, S., and Sheth, N. S.: Species distribution models rarely predict the biology of real populations, Ecography, 2022, e05877, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.05877, 2022.

Ling, N.: Socio-economic drivers of freshwater fish declines in a changing climate: a New Zealand perspective, J. Fish Biol., 77, 1983–1992, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8649.2010.02776.x, 2010.

MacDougall, A. S., Gilbert, B., and Levine, J. M.: Plant invasions and the niche, J. Ecol., 97, 609–615, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2009.01514.x, 2009.

MacNeil, C. and Briffa, M.: Fear alone reduces energy processing by resident `keystone' prey threatened by an invader; a non-consumptive effect of `killer shrimp' invasion of freshwater ecosystems is revealed, Acta Oecologica, 98, 1–5, 2019.

McCarthy, J. K., Wiser, S. K., Bellingham, P. J., Beresford, R. M., Campbell, R. E., Turner, R., and Richardson, S. J.: Using spatial models to identify refugia and guide restoration in response to an invasive plant pathogen, J. Appl. Ecol., 58, 192–201, https://doi.org/10.1111/1365-2664.13756, 2021.

McDowall, R. M.: Gamekeepers for the nation: The story of New Zealand's Acclimatisation Society 1861–1990, Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, New Zealand, ISBN 0-908812-37-X, 508 pp., 1994.

McDowall, R. M.: Historical biogeography of the New Zealand freshwater crayfishes (Parastacidae, Paranephrops spp.): restoration of a refugial survivor?. New Zealand Journal of Zoology, 32, 55–77, 2005.

McGarvey, D. J., Menon, M., Woods, T., Tassone, S., Reese, J., Vergamini, M., and Kellogg, E.: On the use of climate covariates in aquatic species distribution models: are we at risk of throwing out the baby with the bath water?, Ecography, 41, 695–712, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03134, 2018.

Merow, C., Smith, M. J., and Silander Jr., J. A.: A practical guide to MaxEnt for modeling species' distributions: what it does, and why inputs and settings matter, Ecography, 36, 1058–1069, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2013.07872.x, 2013.

Morelli, T. L., Daly, C., Dobrowski, S. Z., Dulen, D. M., Ebersole, J. L., Jackson, S. T., Lundquist, J. D., Millar, C. I., Maher, S. P., and Monahan, W. B.: Managing climate change refugia for climate adaptation, PLOS ONE, 11, e0159909, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159909, 2016.

Mpanza, N. P., Cuthbert, R. N., Pegg, J., and Wasserman, R. J.: Assessing biological invasion predatory impacts through interaction strengths and morphological trophic profiling, Biol. Invasions, 26, 4165–4177, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-024-03435-x, 2024.

MPI: Biosecurity Response to Corbicula fluminea in the Waikato River, Technical Advisory Group Report, Biosecurity New Zealand, https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/59086-Technical-Advisory-Group-Report-Biosecurity-Response-to-Corbicula-fluminea-in-the-Waikato-River Accessed (last access: July 2024), 2023.

NIWA: Freshwater invasive species of New Zealand, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research, https://niwa.co.nz/sites/default/files/Freshwater invasive species of New Zealand 2020_1.pdf (last access: July 2024), 2020.

Parkyn, S. M., Collier, K. J., and Hicks, B. J.: Growth and population dynamics of crayfish Paranephrops planifrons in streams within native forest and pastoral land uses, N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 36, 847–862, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2002.9517137, 2002.

Pebesma, E. J.: Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data, R J., 10, 439, https://doi.org/10.32614/RJ-2018-009, 2018.

Pedersen, T. L.: patchwork: the composer of plots, R package version 1.1.1, Comprehensive R Archive Network, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=patchwork (last access: August 2025), 2021.

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., and Schapire, R. E.: Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions, Ecol. Model., 190, 231–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026, 2006.

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P., Dudík, M., Schapire, R. E., and Blair, M. E.: Opening the black box: An open-source release of Maxent, Ecography, 40, 887–893, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03049, 2017.

Pilowsky, J. A., Colwell, R. K., Rahbek, C., and Fordham, D. A.: Process-explicit models reveal the structure and dynamics of biodiversity patterns, Sci. Adv., 8, eabj2271, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abj2271, 2022.

Pollock, L. J., Tingley, R., Morris, W. K., Golding, N., O'Hara, R. B., Parris, K. M., Vesk, P. A., and McCarthy, M. A.: Understanding co-occurrence by modelling species simultaneously with a Joint Species Distribution Model (JSDM), Methods Ecol. Evol., 5, 397–406, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12180, 2014.

R Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2020.

Rahel, F. J. and Olden, J. D.: Assessing the effects of climate change on aquatic invasive species, Conserv. Biol., 22, 521–533, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00950.x, 2008.

Rahel, F. J., Bierwagen, B., and Taniguchi, Y.: Managing Aquatic Species of Conservation Concern in the Face of Climate Change and Invasive Species, Conserv. Biol., 22, 551–561, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2008.00953.x, 2008.

Rayne, A., Byrnes, G., Collier-Robinson, L., Hollows, J., McIntosh, A., Ramsden, M., Rupene, M., Tamati-Elliffe, P., Thoms, C., and Steeves, T.: Centring Indigenous knowledge systems to re-imagine conservation translocations, People Nat., 2, 512–526, https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.10126, 2020.

Rayne, A., Beaven, K., Clapcott, J. E., Eveleens, R. A., Kitson, J. C., Ledington, J., McIntosh, A. R., McLeod, T., Parata, R. N., and Shanahan, D. F.: Rethinking freshwater translocation policy and practice in Aotearoa New Zealand, N. Z. J. Ecol., 49, 3602, 2025.

Ricciardi, A., Hoopes, M. F., Marchetti, M. P., and Lockwood, J. L.: Progress toward understanding the ecological impacts of nonnative species, Ecol. Monogr., 83, 263–282, https://doi.org/10.1890/13-0183.1, 2013.

Rillig, M. C.: Global change refugia could shelter species from multiple threats, Nat. Rev. Biodivers., 1, 10–11, https://doi.org/10.1038/s44358-024-00002-z, 2025.

Scott, W. B. and Crossman, E. J.: Freshwater fishes of Canada, Bulletin 184, Fisheries Research Board of Canada, Ottawa, 1973.

Simons, M.: Species-specific responses of freshwater organisms to elevated water temperatures, Waikato Valley Authority Technical Publication, 29, Waikato Regional Council, Waikato, New Zealand, 1984.

Somerville, R., MacNeil, C., and Lee, F.: Habitat suitability of Aotearoa New Zealand for the recently invaded gold clam (Corbicula fluminea), N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 59, 762–779, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2024.2368856, 2025.

Stoffels, R.: New Zealand Freshwater Fish Database (extended), Natl. Inst. Water Atmospheric Res. NIWA Sampl. Event Dataset, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), https://doi.org.10.15468/jbpw92 (last access: August 2025), 2022.

Thuiller, W., Lavorel, S., Araújo, M. B., Sykes, M. T., and Prentice, I. C.: Climate change threats to plant diversity in Europe, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 102, 8245–8250, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0409902102, 2005.

Tingley, M. W., Darling, E. S., and Wilcove, D. S.: Fine- and coarse-filter conservation strategies in a time of climate change, Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci., 1322, 92–109, https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12484, 2014.

Unwin, M. J. and Larned, S. T.: Statistical models, indicators and trend analyses for reporting national-scale river water quality, National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research Client Report CHC2013-033, Ministry for the Environment, New Zealand, 71 pp., https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/Files/mfe-statistical-models-indicators-trend-analysis-reporting-national-scale-river-water-quality-2013.pdf (last access: August 2025), 2013.

Usio, N. and Townsend, C. R.: Distribution of the New Zealand crayfish Paranephrops zealandicus in relation to stream physico-chemistry, predatory fish, and invertebrate prey, N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 34, 557–567, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2000.9516957, 2000.

Valavi, R., Guillera-Arroita, G., Lahoz-Monfort, J. J., and Elith, J.: Predictive performance of presence-only species distribution models: a benchmark study with reproducible code, Ecol. Monogr., 92, e01486, https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1486, 2022.

Van Der Putten, W. H., Macel, M., and Visser, M. E.: Predicting species distribution and abundance responses to climate change: why it is essential to include biotic interactions across trophic levels, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., 365, 2025–2034, https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0037, 2010.

Velazco, S. J. E., Rose, M. B., De Andrade, A. F. A., Minoli, I., and Franklin, J.: flexsdm: An R package for supporting a comprehensive and flexible species distribution modelling workflow, Methods Ecol. Evol., 13, 1661–1669, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13874, 2022.

Velazco, S. J. E., Rose, M. B., De Marco, P., Regan, H. M., and Franklin, J.: How far can I extrapolate my species distribution model? Exploring shape, a novel method, Ecography, 2024, e06992, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.06992, 2024.

Verhoef, G. D. and Austin, C. M.: Combined effects of temperature and density on the growth and survival of juveniles of the Australian freshwater crayfish, Cherax destructor Clark: Part 1, Aquaculture, 170, 37–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(98)00394-9, 1999.

Whitehead, A., Fraser, C., and Snelder, T.: Spatial modelling of river water-quality state: incorporating monitoring data from 2016 to 2020, NIWA Client Rep. Minist. Environ. 2021303CH, Ministry for the Environment, New Zealand, 47 pp., https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/spatial-modelling-river-quality.pdf (last access: August 2025), 2022.

Whitehead, A. L. and Booker, D. J.: Communicating biophysical conditions across New Zealand's rivers using an interactive webtool, N. Z. J. Mar. Freshw. Res., 53, 278–287, https://doi.org/10.1080/00288330.2018.1532914, 2019.

Wickham, H., Averick, M., Bryan, J., Chang, W., McGowan, L. D., François, R., Grolemund, G., Hayes, A., Henry, L., and Hester, J.: Welcome to the Tidyverse, J. Open Source Softw., 4, 1686, https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.01686, 2019.

Wisz, M. S., Pottier, J., Kissling, W. D., Pellissier, L., Lenoir, J., Damgaard, C. F., Dormann, C. F., Forchhammer, M. C., Grytnes, J., Guisan, A., Heikkinen, R. K., Høye, T. T., Kühn, I., Luoto, M., Maiorano, L., Nilsson, M., Normand, S., Öckinger, E., Schmidt, N. M., Termansen, M., Timmermann, A., Wardle, D. A., Aastrup, P., and Svenning, J.: The role of biotic interactions in shaping distributions and realised assemblages of species: implications for species distribution modelling, Biol. Rev., 88, 15–30, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-185X.2012.00235.x, 2013.

Zizka, A., Silvestro, D., Andermann, T., Azevedo, J., Ritter, C. D., Edler, D., Farooq, H., Herdean, A., Ariza, M., Scharn, R., Svanteson, S., Wengstrom, N., Zizka, V., and Antonelli, A.: CoordinateCleaner: standardized cleaning of occurrence records from biological collection databases, Methods Ecol. Evol., 744–751, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.13152, 2019.